Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (38 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

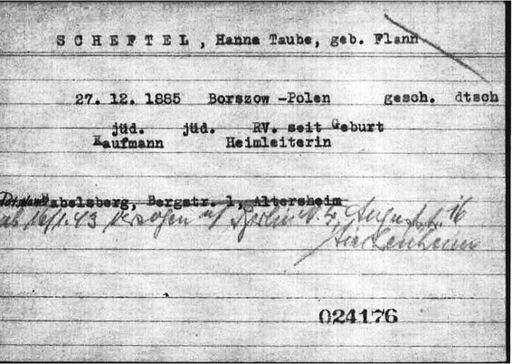

The e-mail continued: “Apart from the transport list we mentioned, we also hold one index card made out by AJDC Berlin”—this was the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the organization survivors once called “the Joint,” formed in the 1910s to help Jewish refugees, and which worked, financially at least, to save Jews during the war—“and another made out by the Reichsvereinigung. Unfortunately, we have no information available on Mrs. Scheftel’s further fate.”

Toni’s Reichsvereinigung card has a typed note indicating her address is Babelsberg, Bergstrasse 1, Altersheim (old-age home)—this is the address Valy wrote from, this was where she was the

Burgfräulein

. I am correct! This is Toni. I write to Jean-Marc, jubilant that I have connected Uncle Julius to Toni to Valy to the old-age home—I nearly shout out loud with my discovery.

On the Reichsvereinigung card, I note that under Toni’s name it first says

“Kaufmann”

(merchant) and then

“Heimleiterin”

(house manager); the Babelsberg address is crossed out, and below it, on January 16, 1943, the Auguststrasse address was written down in pencil. This was the day her old-age home was disbanded, the day when all these elderly men and women were rounded up and sent east to their certain deaths, all these Germans who could well remember a time when Jews were high-standing members of society, war heroes, not pariahs. The home, by then, had become overcrowded, but Toni, Valy writes even before the vise has closed on them, had valiantly tried to keep each member feeling cared for, honored even, until the end. But there is no mention of Valy in the International Tracing Service notes on Toni at all.

Auguststrasse 14/16 is a few doors down from Clärchens, a still-working 1910s-era dance hall once frequented by Nazi officers, with a large beer garden I often biked past. It would have been a strange source of camaraderie and boisterous activity given the tragedy and desperation just a few doors down. Built in the middle of the nineteenth century as a part of the Jewish Hospital, during the Nazi era, while there were still Jewish children in Berlin, Auguststrasse 14/16 housed a Jewish day-care center. Marion Kaplan, in

Between Dignity and Despair

, lays out the scene:

Mothers doing forced labor brought their children to the center around 5 a.m. The children played in the courtyard, took baths, and ate their meals at the center. “They were serious children. . . . They laughed less than others, they also cried less. It was as though they wanted to make as little trouble as possible for us,” reported a caretaker. They were probably also lethargic from malnourishment.

One day, in February 1943, the mothers returned to collect their children after their day of backbreaking, soul-destroying labor, and discovered their kids had been deported, without notice, without their knowledge; there were just the empty prams and scattered toys, the hurried detritus of a group of children gathered up willy-nilly and spirited away. The wailing of the mothers went on for hours.

Auguststrasse 14/16’s day care was called Ahawah—“love” in Hebrew. It was one of a number of day-care centers the Nazis methodically liquidated; the old and the young were useless. Jews, despite themselves, had continued to have children, though far fewer than before the war, and, of course, there was no avoiding getting old. I stand there on the street, listening to the laughter of bicyclists commuting home from work, the sounds of a nearby gallery opening its doors for night visitors, and wonder at the incomprehensible pain this street has seen.

Auguststrasse 14/16 also served as what was then called a

Siechenheim

, a boardinghouse for the old and infirm, as well as a way station for those factory workers who had already been listed for deportation but were deemed too important for the factory to be sent yet—a

Judenhaus

filled, I imagine, with dread and despair. The building has long been in a state of disrepair, enormous, decrepit, seemingly haunted, though recently it began to be rehabilitated, a project funded by the Jewish community.

When I realize that Toni lived here for some months, I head back to the building to look up at it. I go home just after, on the tram, riding through the busy streets of former East Berlin. I am not feeling well at all. I go straight from the train into bed, where I remain for hours, with my head aching and my eyes crossed from the lights I see when I have migraines.

The headache began from my pregnancy, but the idea of the abandoned toys of those long-ago deported day-care children did not help, especially as my little Jew tossed and kicked inside me. Pregnant women did not survive the roundups. They were deported immediately to the east, where many were murdered immediately, or died soon after. The world shimmered from my migraine auras; the pain closed me in, made me claustrophobic, terrified to be alone and terrified of the lights that made the pain worse. I tried to sleep.

Sleep won’t come. Eyes closed to the swirling world around me, I mull over what I know about Toni, Valy’s mother, her only friend, her albatross: I do not know much. I open my eyes in my darkened room. The Joint Distribution Committee—how did Toni have a JDC card? Did Valy have one that I didn’t find? Did the JDC try to enable her—or them—to escape? The organization facilitated the emigration of about 190,000 German Jews from 1938 to 1939, and then worked to help Jews in Hungary and Romania. After the war, the Joint worked to help those who had survived.

The questions keep bubbling back up: The Babelsberg home for the aged was liquidated on January 16, 1943. Neither Valy nor her

mother was sent with the group of elderly. Why were Toni and Valy spared that day? What happened to Valy that day? Where did she go? For God’s sake, where is she? How did she survive? Some of the answers about who Toni was, and the work she did, come in the form of a bulky envelope from the Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv Potsdam, the local state archive for Potsdam.

The archive has several records for Toni—also called “Antonie”—including a letter that spells out, in her own voice, the crushing weight of her continuous impoverishment and explains her role at the home in Babelsberg.

October 8, 1940.

In reply to your valued official communication, I politely inform you that I possess no assets with the exception of a life insurance policy, which does not mature until 1949. Since May 1940 I have been employed by the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland in the Babelsberg Home for the Elderly, 1 Bergstrasse, and my net monthly wage, in addition to board and lodging, is RM 77.52. In the last tax year, I had no income at all and supported myself from the remaining proceeds from the closing down of my household.

It is signed:

Chane Taube Scheftel, Jewess, Place of identity: Berlin, Identity number: A 438802.

Two pages later there is another explanation of her life. “Chane Taube Sara Scheftel, date: October 7, 1940. I was born on December 27, 1885, in Borszczow, and am divorced.” Her property declarations claim she has no possessions of which to speak.

She may have been completely dispossessed by 1943, but from May 1940 until January 1943—or later?—she had had a position of

relative privilege within the Reichsvereinigung, running her old-age home. By the time she is moved to Auguststrasse, she earns 130 RM per month, of which 42 RM are deducted from her already extremely meager wages for her room and board. She is living in one room, with nothing.

I realize I must go backward in time again, to better understand her experience—and thus, also, Valy’s—working in the Reichsvereinigung, and why they were spared for a time.

A few days later, I take the train up to Hamburg to meet Dr. Beate Meyer at the Institut Für die Geschichte der Deutschen Juden (Institute for the History of German Jews) to ask her for help with my questions, the ones I know to ask, the ones I haven’t yet discovered. She has been writing about the Reichsvereinigung for many years, so many that nearly everyone I ask—from the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., to the various academics I consult in Berlin—says things like, “Well, you must have spoken to Beate Meyer? No? Well, then”

—

and so I do. She and I will meet several times, both in Germany and in the United States. She is not terribly keen to be in a story, but she is very willing to talk.

Meyer is soft spoken, with wild, white-blond hair and eyes pouched and weary, behind large glasses, from reading too much about the years of persecution. She is a bit younger than the generation that some in Europe call “’68ers,” one of the generation that turned on its parents, that upended Germany, forced it to look in at itself, at its past.

“In the beginning,” she says, “in the time of emigration,” when emigration was still legal, before October 1941, “there were a lot of people on social welfare . . . people who remained in Germany because their relatives emigrated and they were old people, sick people, children without parents, and so on. They remained in Germany and the Reichsvereinigung had to find homes and orphanages and hospitals and hospices,” she tells me. Jews needed this social welfare network

when they were kicked off the mainstream system; the Reichsvereinigung needed workers to run all those homes, and schools, and spaces. It was work, and it was better than forced labor in the factories, where any rules of health and safety and time management were purposely, cruelly, upended. The Reichsvereinigung was beholden to, really at the whim of, the Gestapo, but also tried to work for the community. That tension held, for a time.

It is a damp day, and the halls of the Institute for the History of German Jews are quiet, save the faint footfalls of the occasional student. It is an old Jugendstil building, with the feel of a hybrid hospital and university. I am hungry and tired and feeling very pregnant though I have months to go before I give birth.

I show Meyer a few of Valy’s letters, especially those that come in October 1941, the moment deportations to the east started and emigration was cut off. When deportations began, Meyer says, Reichsvereinigung officials “had some illusions” about who could stay and who would go. It seemed, at the time, some—possibly like Valy, and certainly like Toni—would remain “necessary” to the Reich—it’s a word that carries great weight in the context of survival, and of creating a hierarchy among Jews. What did they think? I ask, meaning the workers of the Reichsvereinigung, the workers like Valy who made no real decisions about their fellow Jews, but were in the system, somewhere in the mix. What did they know about what it meant to be sent away? And what about the leadership? Did they know much more?

Meyer sighs, heavily. It’s not an easy question—she can’t

know

exactly. But she tries to give me an answer. At first, she says, “the heads of the Reichsvereinigung thought the deportations would only include a part of the Jews, that part would be evacuated and then everything would [settle down] and then everything would . . . They could have community and religious life and could live life as people of . . . yes, as a second class, as underdogs. But they thought they could live [like that] in the German Reich. And they would survive. But in the end of 1941, they realized that that was an illusion—that the

deportations would go on until the last Jew was included.” Belatedly the Reichsvereinigung appealed to the Joint Distribution Committee to procure visas for its higher functionaries. Perhaps that explained Toni’s Joint card, I thought.

Some sixteen thousand Jews were rounded up and expelled from the capital from autumn 1941 to the following fall. The social ostracism was minor in comparison to the terror of daily life. In the late fall of 1942, Jews in Berlin with access to illegal radios heard BBC broadcasts about Jews being murdered by gas. It was, quite literally, unbelievable. And yet, undeniably, people were disappearing, everywhere, most never to be heard from again.

I tell Meyer that Valy writes, desperately, about emigration up until her last letter, hopes for something to come through—to Cuba, to anywhere. I thought that was completely impossible. Meyer says I’m wrong. “Emigration from Germany was still possible until the war began,” she says, despite the curbs on age, on ability to leave, despite dozens of technical obstacles. Small handfuls of people were able to flee. “There were some so-called illegal immigrations when ships were hired and people were put on the ships, but it was not clear that [refugees] could enter a country [they arrived in] or if they would get a visa for a country where they could stay.” Perhaps, I realize with a start, Alfred Jospe was right. With $150 per person, maybe Valy and her mother would have made it to Chile. “The Gestapo tried to force the Jewish people to go on ships but the Reichsvereinigung hesitated,” Meyer explains. “They said, ‘It’s too dangerous.’”