Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History (7 page)

Read Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History Online

Authors: Bryn Barnard

We can blame the British for the spread of cholera. Like other empires before them, the British invaded and connected areas that had previously been isolated from one another. Cholera is endemic to India, killing unnumbered thousands in repeated epidemics since at least 400

B.C.

It even has its own goddess on the subcontinent, Hulka Devi. The first cholera pandemic began in 1817, when Britain was in the process of conquering the subcontinent. British soldiers stationed near Calcutta contracted cholera and carried the disease across the Himalayas to the Nepalese and Afghans they were fighting along India’s northern border. From there, cholera was relayed overland to Burma and Thailand and by sea to Sumatra, Java, China, Japan, Malaya, the Philippines, and Arabia. Slave traders carried the disease south from Oman to Zanzibar. It also migrated up the Persian Gulf to southern Russia. In each of these regions, thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, died in a matter of days. The winter of 1823–24 halted the advance.

The second cholera pandemic started in Bengal in 1826. By 1830, cholera had reached Moscow. By September 1831, the disease was in Islam’s holiest city, Mecca. (It became one of the established dangers of the Muslim pilgrimage, reappearing forty times between 1831 and 1912.) That same year, it reached Berlin and Hamburg.

Cholera became one of the established dangers of the Muslim pilgrimage, reappearing forty times between 1831 and 1912, until strict sanitation, vaccination, and quarantine were practiced. Here, cholera victims are unloaded at the port of Jaffa.

A strict quarantine might have stopped cholera there. But in England, nothing was supposed to stand in the way of the free exchange of goods and services. Businessmen thwarted an attempted quarantine to keep out ships that had visited infected German ports. Soon cholera started sickening people in the English town of Sunderland. Again, business interests argued against quarantine: it would hurt profits, it would cause unemployment. Sunderland was reopened. Cholera spread through England and Ireland, then jumped the Atlantic to North America. Again, tens of thousands died.

We now know something that nineteenth-century people did not: cholera is spread by contaminated water. A look at living conditions in that era helps explain cholera’s global reach. In England, for example, the population was at an all-time high. People were pouring in from the countryside to towns and cities in search of higher wages. Thousands of workers were jammed into cramped, dark, poorly ventilated housing. Why dark? Since 1696, the Window Tax imposed a duty on dwellings with more than six windows. Clear glass was a luxury. To show off their

wealth, the super-rich demanded homes with as many windows as structurally possible. Landlords, on the other hand, and even some members of the middle class, installed few windows. They even bricked over windows in some buildings to stay below the taxable number. People rarely washed their hands in those days, and in their gloomy, stuffy homes, they couldn’t see well enough to clean.

Sanitation was inadequate to nonexistent. Although flush toilets had been used in England since at least the sixteenth century (Queen Elizabeth I got hers in 1597), most human waste was disposed of in pit outhouses. A landlord might provide one over-burdened, rarely emptied privy to serve thirty families. When it overflowed, fecal matter was deposited elsewhere: in cellars, in ditches, or in the street. In London, human waste would eventually end up draining into the Thames River, a malodorous sewer nicknamed “the Big Stink” that was also the final repository of butchers’ offal, tannery effluent, and household garbage. It was the city’s main source of drinking water.

Under such conditions, disease was rampant. Aside from cholera, people suffered from “summer diarrhea” and epidemics of waterborne typhoid, lice-borne typhus, tuberculosis, influenza, and more. People died at rates not seen since the Black Death. Cities needed a continuous flow of new people from the relatively healthy countryside just to keep their population level. No wonder large families were encouraged.

Death rates were highest among the poor. They ate bad food and got little of it. They lived in small, poorly constructed, hard-to-heat dwellings awash in human waste. They wore the theadbare castoffs of their betters. Ill-fed, ill-housed, and ill-clothed, their immune systems compromised, it is no wonder the poor died young. Britain’s upper classes assured themselves that this grotesque disparity was divinely ordained. Poverty was not an economic or social problem but a spiritual condition, a punishment for sin. With the passage of the 1832 Anatomy Act, poverty also became, in effect, a crime. Postmortem dissection by surgeons, anatomists, and medical students, formerly a punishment inflicted only on the very worst condemned criminals, now became instead the fate of paupers unable to pay for their own burials. The Poor Law Amendment of 1834 tightened the noose, outlawing cash charity to the unemployed poor and forcing them into the prison-like workhouse—even orphans, the elderly, and the disabled.

Edwin Chadwick, a reforming civil servant, documented the conditions affecting the poor with his

Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain,

presented to Parliament in 1842. Chadwick asserted that the squalid existence of Britain’s poor was involuntary. He compared it unfavorably to American slavery. Chadwick also revealed that country people lived longer than townsfolk. In a city like Leeds, laborers could expect to die, on average, at age seventeen. Tradesmen died in their mid-twenties. Even the privileged gentry usually survived only into their forties. You might make more money in a city, but you wouldn’t live long to enjoy it.

Chadwick, who lived to be ninety, thought this a waste. He was an advocate of utilitarianism, the belief that government should act to create “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” He argued that better living conditions would allow poor people to work harder and be less of a burden on society. Chadwick was also a miasmist. He declared that “all smell is disease.” Get rid of the smell, Chadwick reasoned, and you get rid of the disease. He recommended improved housing, paved streets, clean drinking water, flush toilets, and efficient sewers for everyone. Opponents called this “mawkish philanthropy,” but after years of bickering and thousands more cholera deaths, Parliament began to implement Chadwick’s reforms with the first Public Health Act of 1848. The Window Tax was repealed in 1851. The third cholera pandemic started in 1853, killing fifteen thousand people in England alone. It helped spur the Sanitary Act of 1866, the second Public Health Act of 1872, and the third Public Health Act of 1875.

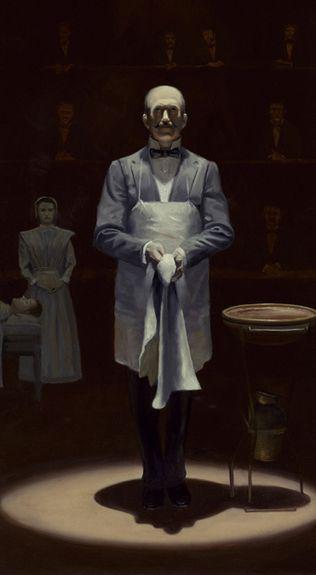

Just as important as Chadwick in the prevention of cholera was Ignaz Semmelweis’s advocacy of hand washing. In 1846, Semmelweis was a Hungarian obstetrician working in Vienna. It is hard to believe now, but in those days even well-off Europeans rarely washed their hands. No wonder: not all homes or businesses had piped-in water, and hot water had to be heated on a stove. With knowledge of microbial pathogens still in the future, the need for regular, systematic hand washing wasn’t understood. Semmelweis, however, pointed out that women who gave birth with midwives (or even on the street) had a

much better chance of survival than those who delivered their babies in crowded hospitals, where doctors worked ungloved and wore the same attire throughout the day. For surgeons, bloody aprons were a sign of professional prowess—the redder the better. Semmelweis suggested that physicians were passing a fatal “something” from sick and newly dead patients to healthy mothers. Although doctors were incensed at the accusation that they were contagious, Semmelweis ordered his subordinates to wash their hands in chlorinated water before entering his wards. The maternal death rate dropped from 30 percent to 1 percent. The Semmelweis technique spread from hospitals to businesses, schools, and homes as a cheap, effective way to stop illness. It still is.

Ignaz Semmelweis introduced modern hand washing into his maternity wards. He dropped the death rate from thirty out of a hundred to one.

Though the Chadwick reforms and the Semmelweis method improved urban life expectancy and helped curb cholera, the disease remained a huge health problem. In 1854, a London physician named John Snow noticed that in Soho many cholera deaths were concentrated around the Broad Street public pump. To see if water pollution was the cause, he removed the handle so that the pump could not be used. Neighborhood cholera deaths plummeted. Eventually Snow compiled a detailed survey of the many competing companies that supplied water to London, each with its own overlapping systems of pipes. He conclusively connected cholera with the sewage-contaminated drinking water of one company, drawn downriver from London. More investigation showed that of London’s eight private water companies, only five filtered their water. (One customer found his pipes clogged by a rotting eel!) Snow was attacked for his ideas by miasma-obsessed sanitationists, who feared his focus on waterborne contagion would slow the cleanup of the English slums. But by 1902, London had merged its private water companies into a single municipal corporation that supplied everyone in the city with filtered, chlorine-treated water. Cholera and other waterborne diseases faded. Health improved.

These changes were noted and copied elsewhere. In Germany, renowned pathologist Rudolph Virchow designed a new sewer system for Berlin. In the United States, Dr. John H. Griscom adapted Chadwick’s theme and title for his influential 1845 tract,

The Sanitary Condition of the Laboring Population of New York.

Jacob Riis’s 1890 blockbuster,

How the Other Half Lives,

also helped ignite American reform. Across Europe and America, and later Japan and other parts of the industrializing world, cities were transformed from fetid sties to livable metropolises with improved housing, efficient sewers, clean piped water, and regular garbage removal.

To understand the importance of these changes, one has only to look at the fate of an industrial nation denied the basics of modern life. Iraq is an instructive example. Though the dictator Saddam Hussein ruled Iraq for much of the late twentieth century, the country was modern and prosperous, with a large, educated middle class concentrated in cities like Baghdad, Fallujah, and Basra. In the 1990s, however, the United Nations implemented sanctions that denied Iraq critical water treatment system parts and medical

supplies the Iraqi government might have also been able to use to manufacture weapons. The health effects were immediate, widespread, and ghastly. Infant mortality rose sharply. Infectious diseases spread. Cholera returned. In all, about a million Iraqi children died. Any other industrial country denied essential modern sanitation would suffer a similar outcome.

Thirty years, two cholera pandemics, and hundreds of thousands of deaths after John Snow’s observations, the great German biologist Robert Koch finally discovered the microbe responsible for cholera. In 1883, during the fifth pandemic (1881–86), Koch beat his archrival, Louis Pasteur, by identifying the cholera vibrio in the disease’s homeland, India. Koch became a German national hero. (

Vibrio

is one of the many shape-based words still used to describe bacteria. A vibrio is comma-shaped. A bacillus is rod-shaped. A spirochete is screw-shaped. A coccus is round.)