Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (87 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

To have any confidence about breaking the Red Army's resistance and ending the war in 1941, a great deal of hope was placed in the refitting of the two panzer groups in Army Group Centre that had been underway since early August.

Guderian had originally said he would have finished his refitting by 15 August, but delays in the arrival of spare parts and replacement engines, as well as the constant action of his forces especially in the south, meant that his panzer group was scarcely in better shape than before the refitting began. On 19 August Panzer Group 2 notified Army Group Centre of the results of its refitting and the subsequent combat readiness of its panzer corps.

Schweppenburg's XXIV Panzer Corps and

Lemelsen's XXXXVII Panzer Corps were still in action south

of Roslavl and their respective time spent refitting was reported as: ‘XXIV

Panzer Corps at no time since the beginning of the war. XXXXVII

Panzer Corps only with the

18th Panzer Division fully allowed rest.’ The recommendation of the panzer group was that both panzer corps needed ten days of technical refitting to make good material losses and four days of rest for the personnel. Vietinghoff's

XXXXVI Panzer Corps was only relieved from its latest commitment to the volatile Yel'nya salient on the same day the report was prepared (19 August), and even then one brigade remained at the front. The corps was reported to be in need of rest and repairs, which for personnel and equipment would require until 23 August. Yet undermining any prospective extension to the refitting process were the same two problems which until now had proved so detrimental. The first was the constant commitment of panzer forces to action, and the second was the persistent lack of spare parts. Even on 19 August, four days after the refitting was due to be completed, Panzer Group 2 informed Bock's command: ‘The technical refitting of all corps depends on the arrival of the spare parts.’ Furthermore, with a view to the worn and dust-spoilt engines of the panzer group, the report advised that future operations would need to take into account the increased oil consumption.

233

As an example of how extreme the situation was becoming, the

10th Panzer Division reported on 17 August:

The condition of the trucks is in large part bad…For major repairs, which are necessary for many trucks, there are no spare parts. It must therefore be understood that with the beginning of a new operation, trucks will have to be towed in order to take them with

us.

234

Hoth's

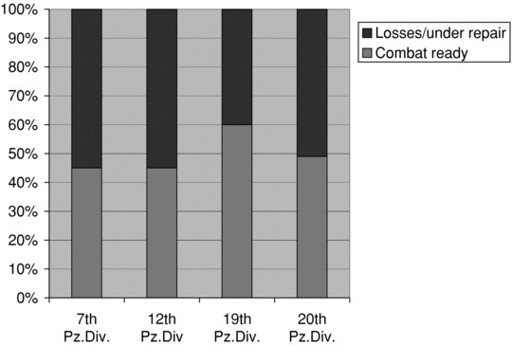

panzer group also prepared a report to Army Group Centre on its combat readiness with a similarly pessimistic conclusion regarding its success in refitting the panzer divisions. Hoth had originally stated that his refitting would be finished on 20 August, but the report produced on 21 August revealed that the number of available panzers had not substantially increased at all. Figures for the combat readiness of the individual panzer divisions were listed as follows:

7th Panzer Division 45 per cent (it had been at 60 per cent until the aforementioned total loss of 30 panzers),

19th Panzer Division 60 per cent,

20th Panzer Division 49 per cent and

12th Panzer Division 45 per cent

(see

Figure 9.4

).

235

The overall average panzer strength was therefore about 50 per cent, which is the same figure Halder reported almost a month before at the end of the long advance towards Smolensk.

236

Figures demonstrating personnel shortages also highlight the manpower deficiency within the panzer group. The 19th and 20th Panzer Divisions were at 75–80 per cent of full strength. The 7th Panzer Division was at 70 per cent strength and the

14th Motorised Infantry Division was at 50–60 per cent strength. Both of these divisions, however, were expected to be raised to 80 per cent strength with the arrival of reinforcements, although it is not clear from the document when this was expected to take place.

237

The serviceability of trucks for the panzer group was one area where the refitting period appeared to have made some significant improvements, although these were, in practice, short-term remedies. At

first glance the figures appear rather encouraging. Among the motorised infantry divisions the

20th was at 92 per cent of full strength, the 14th at 90 per cent and the

18th at 75 per cent strength. For the panzer divisions the results were somewhat less successful. The 12th was at 82 per cent of its full complement, the

19th at 80 per cent, the

7th at 75 per cent and the 20th at 70 per cent. As if to dissuade Bock's army group from drawing an overly optimistic conclusion, it was made clear that the high number of French vehicles in the panzer group were almost at the end of their serviceability. For example, it was warned that the trucks in the

14th Motorised Infantry Division, which was now outfitted with 90 per cent of its original fleet, had ‘only a limited life expectancy’. Similarly the

20th Panzer Division, with 70 per cent of its full strength, was noted to have ‘French trucks, which will not survive much longer’.

238

Yet, even for those divisions with German trucks, the outlook was not fundamentally different and the prospect of a long advance over terrible roads would quickly see a sharp spike in the fallout

rate.

Figure 9.4

Figure 9.4

Combat readiness of Panzer Group 3 on 21 August 1941. ‘Panzerarmeeoberkommandos Anlagen zum Kriegstagesbuch “Berichte, Besprechungen, Beurteilungen der Lage” Bd.IV 22.7.41–31.8.41’ BA-MA RH 21–3/47, Fols. 78–79 (21 August 1941).

On

22 August Army Group Centre's war diary concluded: ‘The armoured units are so battle-weary and worn-out that there can be no question of a mass operative mission until they have been completely replenished and repaired.’

239

Two days later General

Buhle reported to Halder that the combat strength of the infantry divisions across the eastern front had been reduced on average by 40 per cent and the panzer divisions by 50 per cent.

240

By the end of August panzer losses across the whole of the eastern front had reached 1,488, with Hitler still determined to withhold most of the new domestic production of panzers for later campaigns. As a result, only 96 replacements were released out of 815 new models produced between June and August 1941. Based on starting totals given on 22 June 1941, on 4 September the number of available panzers were as follows: total losses constituted about 30 per cent, those classified as under repair came to 23 per cent, leaving just 47 per cent ready for action. Within Army Group Centre, however, only 34 per cent of tanks were classed as ready for action.

241

Hoth's panzer group, reduced to three panzer divisions

after the

12th Panzer Division was subordinated to the

16th Army, retained only 41 per cent of its initial strength (see

Figure 9.5

). Guderian's panzer group, reduced to four panzer divisions after the

10th Panzer Division was subordinated to

4th Army, fielded just 25 per cent of its original strength (see Figure 9.6).

242

The fact that Bock's advance had already been stalled for a month clearly shows that the stiff Soviet resistance had had a ruinous impact on German plans. Even after the long pause, on 22 August large-scale operations were judged to be out of the question. At the same time, a long-term defence of the eastern front was determined to be ‘

unbearable’.

243

The principal commanders at Army Group Centre and at the OKH correctly determined that Hitler's preference for a southward swing would not lead to a comprehensive victory over the Soviet Union in 1941, yet their own plans for shattering the Red Army and seizing Moscow were reflective of the same wildly unrealistic optimism that had undermined Barbarossa from the very beginning. By the end of August it was clear that Operation Barbarossa would fail in its essential goal to conquer the Soviet Union, which by extension destined Germany to almost certain defeat in a world war. The short window of opportunity to strike down the Soviet colossus had passed and the so-called ‘Russian front’ would continue to devour strength at

an insufferable rate for German manpower reserves and military production. The arrival of winter would hit the struggling German armies with devastating effect and complete the ‘hollowing out’ of German divisions, leaving many undermanned and inadequately equipped for much of the rest of the war. The implications of Barbarossa's failure were already disturbingly apparent to some commanders. Hans von

Luck records the commander of the 7th Panzer Division telling his men: ‘This war is going to last longer than we would like…The days of the Blitzkrieg are over.’

244

Another German officer, Colonel Bernd von

Kleist, described the situation metaphorically: ‘The German Army in fighting Russia is like an elephant attacking a host of ants. The elephant will kill thousands, perhaps even millions, of ants, but in the end their numbers will overcome him, and he will be eaten to the bone.’

245

On the Soviet side, Stalin's most successful commander of the war, Marshal

Zhukov, summed up the German summer campaign.

Figure 9.5

Figure 9.5

Combat readiness of Panzer Group 3 on 4 September 1941. Burkhart Müller-Hillebrand,

Das Heer 1933–1945

, Band III, p. 205.

Figure 9.6

Figure 9.6

Combat readiness of Panzer Group 2 on 4 September 1941. Burkhart Müller-Hillebrand,

Das Heer 1933–1945

, Band III, p. 205.

Gross miscalculations and mistakes were made in political and strategic estimates. The forces at Germany's disposal, even including satellite reserves, were clearly inadequate for waging simultaneous operations in the three major sectors of the Soviet–German front. Because of this the enemy was compelled to halt his drive

towards Moscow and to assume defensive positions on that front in order to divert part of the forces of Army Group Centre to the support of Army Group South, facing our troops on the Central and Southwest

fronts.

246

While the German generals later found it convenient to blame Hitler's interference, the harshness of the Soviet climate, and the sheer numerical superiority of the Soviet Union, the fact remains that their plans for the conquest of the Soviet Union were simply attempting too much. Germany's successes in the early weeks of the war were enough to severely batter the Red Army, yet these came at an unexpectedly high cost to the motorised divisions upon which the blitzkrieg's success depended. While Germany still needed to do more – in fact much more – to topple the Soviet Union in late August 1941, the offensive strength simply no longer existed.