On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (21 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

When demons do shape-shifting and other seemingly supernatural marvels, they are not creating so much as altering nature. According to Institoris, the evil ones sift the matter of nature to find the seeds (

semina

) of transformation, and then use these micro-agents as catalysts for their own nefarious inventions.

32

Demons transform nature more by chemistry than by magic. Just as the form of the oak tree exists as a germ in the acorn, so too all of nature is filled with microseeds that, when triggered, alter the perceivable world in significant ways. Demons understand these mechanisms, which are invisible to humans, and they engineer outcomes in ways that look miraculous to us. By this subtle knowledge of nature witches appear to predict the future, but they cannot really do so, as God can. In this way, Institoris explains how demons and witches create mayhem in the world, but he avoids the heresy. Demons simply

alter

nature in ways that scare and frighten us and seem supernatural.

33

Now we finally see why “God’s acquiescence” is frequently intoned in the explanation of witchcraft offered in the

Malleus

. The logic is this: even if witchcraft is only altering nature rather than creating it, it’s still doing significant damage in the world. Nature is being altered by demons in ways that allow witches to kill their neighbors with clay effigies and pins. And letting insignificant chump demons and their paltry witch covens undo the beautiful divine cosmic plan would reflect very badly on God, unless God was actually giving his permission for this suffering.

Why

he gives his permission to let demons and witches turn some kid’s hand upside down is really beyond the speculative power or will of the demonologist. What matters is that the witch’s monstrous activity has been theoretically integrated with Christianity.

Metaphysics aside, the fascinating psychological dimension of all this inquisitorial interest in fornication is often given a Freudian interpretation. Sexual repression probably makes sense out of much of the tone of Catholic writings about sexuality and the body, but then one still wants to know

more about why the repression developed in the first place. Repression is a tool for handling the always threatening emotional brand of possession. This topic is too vast to engage here, but some brief comparison with the ancients regarding monstrous eros seems useful.

In the same way that desire, in its most primitive form, frightened the ancient Greeks and Romans, erotic urges also plagued the medievals. The

Malleus

portrays almost all such cases of lust as cases of demonic possession or witch manipulation. Whereas the possession language tended toward the metaphorical in many ancient sources, it becomes quite literal in the

Malleus

. The loss of rational control and the fire in the loins seem perennial, but the cause of these symptoms is now clearly identified as Satan and his minions.

Institoris tells a brief story to illustrate the corruption of “those subject to excessive love or hatred.” In the diocese of Konstanz, Germany, a beautiful virgin lived simply and piously. A “certain man of loose character” took a lascivious interest in her; in fact he was entirely overcome with the infatuation. “After a while he did not have the strength to conceal the wound to his sanity. So he came to the field where the said virgin was working and, expressing himself decorously, revealed that he was in the net of an evil spirit.” She rebuffed his advances; he grew angry and vowed to have her by magical means, if need be. They parted. Sometime later, after an interval of feeling “not a spark of carnal love for the man in herself,” the virgin began to “have amorous fantasies about him.” By most standards, this eros episode is pretty mild stuff, no real drama to speak of. But even here, when the actors appear to be in relative possession of themselves, Institoris is convinced that demons are squirming in every act of the tepid tryst. The horror of giving in to temptation is averted, thankfully, when the virgin makes haste to her confessor and unloads the terrible burden of her wicked feelings. Confession, together with a pilgrimage to a holy site, sets the girl in order and, more important, smooths the bumpy terrain of her soul so that no demon can find traction there and no male witch can coerce her emotions with magical techniques.

Lack of self-control, here made literal as possession and magical manipulation, is the same monster we encountered before. But the difference between Stoic madness and Christian is that not only can you no longer answer to yourself, tossed and frayed as you are by your own craving, but now you can no longer answer to God. Taming your internal monsters is not only good advice for living well (the Greek

eudemonia

), but now it is also allegiance to the will and plan of the deity.

All this talk of discipline and desire raises an important general question about witches, one that Institoris addresses directly. Granted that they

could be found in either gender, why were so many of the accused witches women? One answer is that women were considered the carnal flashpoints for any man’s spiritual journey. Just as God was using demons to punish fallen humans, demons were using women to tempt the fall of priests, monks, and husbands. Women could be highly effective tools in the devil’s attempt to dismantle men.

34

But another explanation, more physiological in tone, held that women were more completely dominated by sexual lust; their receptacle natures were always in need of filling, and this made them crave penetration. Institoris says that one part of the woman that “never says ‘enough’” is the “mouth of the womb.” Consequently, women’s amorous condition makes them easy targets for demons who wish to find some way to influence affairs. And this natural lustful condition makes women proficient temptresses without much effort or study. All the other usual stereotypes are trotted out to buttress this view: a woman is more credulous and therefore open to superstition; a woman will talk incessantly

in groups and therefore easily transmit the demonic information, creating covens; and “when she hates someone she previously loved, she seethes with anger and cannot bear it,” therefore she is quick to engage in the revenge and retribution tactics so prevalent among witches.

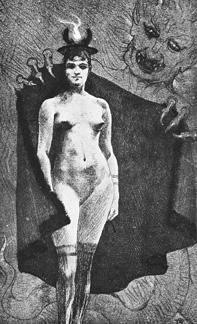

Demonization and gender. An example of “woman as dangerous monster.” Here, in Felicien Rops’s drawing

The Organ of the Devil

, we find Satan unveiling the tempting nude female. Sexual liberation has played an ongoing role in the clash of civilizations. From Edward Lucie-Smith and Aline Jacquiot,

The Waking Dream: Fantasy and the Surreal in Graphic Art 1450–1900

(Knopf, 1975).

Finally, we must turn to solutions. What can be done about these monsters? How can we defeat the demons and the witches? Witches were tested using trials by ordeal (e.g., carrying red-hot iron, being dunked in water, being pricked) and torture (e.g., stretching and dislocating limbs with ropes and levers, and virtually anything else a sadistic imagination can dream up). How one interpreted the trial by ordeal was rather inconsistent; some accepted a miraculous ability to carry hot iron as evidence of innocence and God’s favor, while others (Institoris in some passages) suggested that such lack of injury be taken as satanic protection. When the witch confessed to black arts and named others, she was often exiled, imprisoned, burned, or hanged. When the witch refused to confess such atrocities, particularly after significant torture, she was said to be especially strengthened by Satan and subsequently sentenced to burning or hanging. Not much rehabilitation or healing existed for witches, only degrees of punishment.

Those who were possessed were in a different position. In the case of possession, the person afflicted was not considered to be evil or malicious but set upon, not entirely responsible for his or her actions. In these cases, the person’s monstrous behavior could be exorcised and he or she could be restored to fully human status. Interestingly, Institoris notes that when exorcism fails after multiple attempts, the victim may have been misdiag-nosed and probably deserves his or her condition as a divine punishment.

A typical exorcism is outlined by Institoris.

35

It’s best if a cleric performs the function, but anyone of good character can do it if necessary. First, the afflicted person must be made to confess. Next, a careful search of the home must be made to detect any magical implements (e.g., amulets, effigies), and these must be burned. It is important to get the individual into a church at this point, and he or she should be made to hold a blessed candle while righteous witnesses pray over him or her. This should be repeated three times a week to restore grace, and the victim should receive the holy sacrament. In stubborn cases, the beginning phrases of John’s Gospel should be written on a tablet and hung around the person’s neck, and holy water should be applied liberally. If exorcism ultimately fails, then either the person is being punished by God and has to be surrendered, or

the faith of the exorcist was not strong enough and new administrators might be brought in.

The message of medieval monsterology is that the causes and cures of monsters are spiritual in nature. Human pride may bring them out, but they are metaphysically real. Heroism of the pagan variety will not conquer the monsters. Only submission to God and humility will beat back the enemy.

3

Scientific Monsters

The Book of Nature Is Riddled with Typos

Natural History, Freaks, and Nondescripts

We ought to make a collection of all monsters and prodigious births, and everything new, rare, and extraordinary in nature

.

LORD FRANCIS BACON

THE HYDRAI must have the fat boy or some other monster or something new

.

P. T. BARNUM

I

N THE

1730

S A YOUNG

Carl Linnaeus stood before a monstrous creature in Hamburg. Legend held that the creature had been killed several centuries earlier and its stuffed remains looted after the 1648 battle with Prague, eventually becoming the prized possession of Count Konigsmark. When Linnaeus examined it, the creature had only recently come into the collection of the burgomaster of Hamburg. Linnaeus, who later became the greatest naturalist of the modern era (second only to Darwin perhaps), had traveled from his home in Sweden to examine the “curiosities” of the continent, including Jews (who were then banned in Sweden).

1

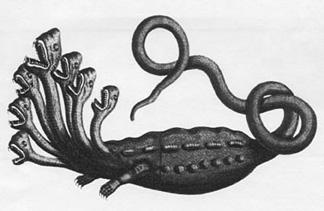

The monster of the burgomaster’s cabinet, with seven heads, sharp teeth, frightening claws, and a giant snake-like body, was called a hydra. It was already a well-known subject of the science of the day because drawings of it had been included in many celebrated natural history compendia, such as Albertus Seba’s

Thesaurus

. The hydra of Hamburg was just one of many monsters populating the collections and imaginations of eighteenth-century Europeans, and it represented the frightening unknown dimension of a

nature

that was permeated with the

supernatural

. For Linnaeus and many other gentile Europeans, Jews and hydras and other aliens represented the sublimely vast and menacing

terra incognita

, an unknown frontier, barely touched by the tiny border where new sciences forged ahead.

A drawing of the hydra monster that Linnaeus eventually debunked as a taxidermy hoax. From Albertus Seba’s compendium

Cabinet of Natural Curiosities

, republished by Taschen Books, 2005. Reprinted by kind permission of Taschen Books.

When Linnaeus arrived to study the hydra, the burgomaster was in negotiations to sell the monster at a significant profit; even the king of Denmark had made an offer. But Linnaeus’s careful eye detected the skilled hand of a deceptive taxidermist. The clawed feet and the teeth appeared to be taken from large weasels; the body was a graft of mammal parts carefully covered in places with various snake skins. Linnaeus believed that the creature had been fashioned by Christian monks to serve as frightening evidence to the faithful that the Apocalypse was imminent. He conjectured that the creature was supposed to be a portentous dragon from the Book of Revelation fabricated to scare the wayward flock.