On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (16 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

The xenophobic idea of dangerous monsters culminated in a popular story about Alexander’s gates. The European version of the story, of a barrier erected against barbarian enemies, seems to have first appeared in sixth-century accounts of the

Alexander Romance

, but the legend is probably much older. Alexander supposedly chased his foreign enemies through a mountain pass in the Caucasus region and then enclosed them behind unbreachable iron gates. The details and the symbolic significance of the story changed slightly in every medieval retelling, and it was retold often, especially in the age of exploration.

By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the meaning of Alexander’s gates had long since been Christianized and played an important role in both the geography of monsters and the ultimate end-time purpose of the fiends. The maps of the time, the

mappaemundi

, almost always include the gates, though their placement is not consistent. Most maps and narratives of the later medieval period agree that this prison territory, created proxi-mately by Alexander but ultimately by God, houses the savage tribes of Gog and Magog, who are referred to with great ambiguity throughout the Bible, sometimes as individual monsters, sometimes as nations, sometimes as places. In the story of Alexander’s gates, a kind of synthesis occurs, in which “Gog and Magog” becomes a label for designating infidel nations and monstrous races, a monster zone, which different scribes can populate with all manner of projected fears.

Mathew Paris was the chronicler of the Benedictine abbey of St. Albans in England from 1235 to 1259, and he drew up a series of influential maps, usually with Jerusalem and the Holy Land as the central focus. In his maps he placed the monster zone of Gog and Magog in northern Asia and populated it with Tartars (multiethnic Muslim populations).

35

The British Hereford

mappamundi

(ca. 1300) continued the tradition of moral

geography, placing Jerusalem as the righteous navel, with lesser known territories, some quite deviant, near the perimeter.

36

In addition to the

Alexander Romance

, the Hereford map drew heavily for its source material on the writings of Solinus, a fourth-century author of

De Mirabilibus Mundi

(On the Wonders of the World). The

Mirabilibus

itself drew significantly on Pliny’s

Natural History

and therefore repeats the familiar monsters of the ancient world. But now the creatures, including the dog-headed Cynocephali, the Satyrs, the Blemmyae, the cannibal Anthropophagi, and others, are all reconceptualized as players in the metaphysical geography of Christianity.

The Hereford map shows the people of India as exotic, but it does not disparage them. The inhabitants residing along the Nile, however, are characterized as deformed and less civilized. But the full weight of aversion is saved for the northern perimeter of the map, in Scythia, where live the worst monsters, who are shut up behind Alexander’s gates. Here we find the Arimaspeans, the one-eyed race of men, together with their enemies, the gold-digging half-lion, half-eagle griffins. But most important, the map warns us that in this region “everything is horrible, more than can be believed” (

Omnia horribilia plus quam credi potest

). The map continues its description: “Here there are very savage men feeding on human flesh, drinking blood, the sons of accursed Cain. The Lord closed these in by means of Alexander the Great…. At the time of the Antichrist they will break out and will carry persecution to the whole world.” Here we find two extremely popular late medieval ideas: that the monstrous races are descendants of Cain and that when the end of times comes they will join forces with the Antichrist and persecute the righteous.

The late medieval theorists reach back to a figure after Adam but before Noah in order to isolate the cause of monsters. Recall that Adam and Eve (in Genesis 4) give birth to Cain and Abel, and while both of them make a sacrifice to God, only Abel’s blood sacrifice is pleasing to God. In retaliation, supposedly, Cain kills his brother and becomes ever after cursed by God to live on earth marked as an outcast who can’t get any of his crops to grow. Cain seems a perfect candidate for monster race paternity.

A twelfth-century German version of this biblical story, called the Vienna Genesis, analyzes the genealogical story more fully.

37

Here we find that Adam’s third son, Seth, about whom little is said in the scriptures, is the offspring who “replaces” the physical loss of Abel and the moral and spiritual loss of Cain. It is the pure and righteous Seth who eventually gives rise to the normal human races of the earth, including, significantly, the lineage that gives rise to Jesus. Cain, on the other hand,

becomes the progenitor fall guy for every subsequent nefarious character and creature.

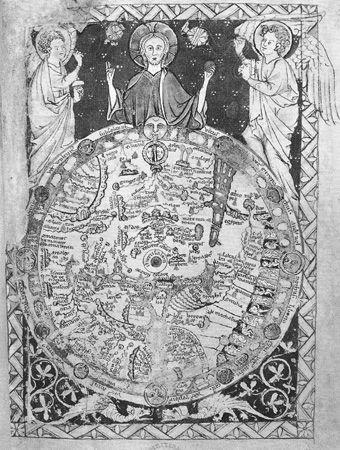

The Psalter

mappamundi

(ca. 1225) continued the tradition of moral geography, placing Jerusalem as the righteous navel, with lesser known monster territories near the perimeter. Courtesy of the British Library.

In the

Zohar

of the Kabbalah the Jewish midrash tradition further develops the Cain story, suggesting that Cain’s own depravity was partly genetic. Cain’s mother, Eve, fouled the bloodline by having a relationship with the serpent: “When the serpent injected his impurity into Eve, she absorbed it and so when Adam had intercourse with her she bore two sons—one from the impure side and one from the side of Adam….Hence it was that their ways in life were different….From [Cain] originate all the evil habitations and demons and goblins and evil spirits in the world.”

38

Apocryphal scriptures, legends, and even the pictorial traditions tend to

characterize Cain as misshapen, with horns and lumps on his body, and often draped in fur pelts like a feral man. But this story is important for the way that it broadcasts the tendency in ancient and medieval thought to connect sin and heredity, the tendency to explain monsters and evil generally as the result of unholy sexual union or dysgenics. In the late medieval mind, these myriad errant offspring could be localized in one contained place.

The monsters’ incarceration behind Alexander’s gates is only temporary. They await their imminent release, the medievals believed, and will be upon us shortly. The

Travels of Sir John Mandeville

(published between 1357 and 1371) reveals precisely how this unleashing will finally occur.

42

Mandeville retells the story of a monster zone full of dragons, serpents, and venomous beasts in the Caspian Mountains, but he adds another ethnic group, indeed, what he considers the main ethnic group, to the famous confinement. In chapter 29 he writes, “Between those mountains the Jews of ten lineages be enclosed, that men call Gog and Magog and they may not go out on any side.” Here he is referring to the legendary ten lost tribes that disappeared from history after the Assyrian conquest in the eighth century

BCE

.

40

These Jews, according to Mandeville, will escape during the time of the Antichrist and “make great slaughter of Christian men. And therefore all the Jews that dwell in all lands learn always to speak Hebrew, in hope, that when the other Jews shall go out, that they may understand their speech, and to lead them into Christendom for to destroy the Christian people.”

Christian paranoia about Jews is, of course, an old story. Here in Mandeville we find a late medieval anti-Semitic maneuver that linked Jews directly with other monsters behind the gates and also gave Christians reason for increased paranoia about the local Jewry. To Christians, Jews were proximate in-house monsters (the Diaspora) who also had genealogical relations with the most foreign and distant of monsters. Anti-Semitism didn’t really need help from Mandeville’s like because the pious fury of the formally anti-Muslim crusades (1095–1291 and beyond) had been spilling over to include violence against local Jewry for centuries. The religious zeal of a Christian warrior culture marching to retake the Holy Land from the infidels did much damage to Jews in France, Germany, Hungary, England, Syria, and Palestine. In a demonstration of Freudian aggression theory, Christians who were frustrated in their desires to beat down their Muslim enemies vented spleen on their in-house “foreigners,” the Jews. Christian forms of anti-Semitism, which had long demonized Jews for killing Christ, offered ready-to-hand justifications for such massacres, and now Mandeville simply added more fuel to the fire.

It is ironic that Mandeville displays greater tolerance of and appreciation for Muslims (Saracens), the actual targets of the recent crusades, than he shows for Jews. Mandeville claimed that the Muslims, though wrong and dangerous, still had so much theological common ground with Christians (e.g., acceptance of the same scriptures, acceptance of the importance of the same prophets and the importance of Jesus and Mary) that conversion to Christianity was eventually quite possible. The Muslims were monstrous on the surface, but theological solidarity made their redemption imaginable.

41

Why this same charity was not extended to the Jews is somewhat unclear, but it appears to be the result of the long-standing culture of blame that saw Jews as responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus (a putative culpability not shared by the Saracens).

42

More prosaically, the resentment of Christian merchants and ecclesiastics who were defaulting on their Jewish loans often led to ethnic-based condemnations of moneylending. All these demonizations and projections conspired until Jews were eventually expelled from England (1290), France (1306, 1322, and again 1394), and Spain (1492).

43

“Anti-Semitism,” according to Judith Taylor Gold, “is the perception of the Jew as a monster.”

44

In the end, Mandeville predicts, a lowly fox will bring the chaos of invading monsters upon the heads of the Christians. He claims, without revealing how he comes by such specific prophecy, that during the time of the Antichrist a fox will dig a hole through Alexander’s gates and emerge inside the monster zone. The monsters will be amazed to see the fox, as such creatures do not live there locally, and they will follow it until it reveals its narrow passageway through the gates. The cursed sons of Cain will finally burst forth from the gates, and the realm of the reprobate will be emptied into the apocalyptic world.

It would be unfair to leave the reader with the impression that Mandeville’s

Travels

is just an excuse for intolerant prejudices. It is, in fact, only slightly concerned with Jews and Muslims, and is instead a wonder-filled compendium of weirdness. Mandeville’s fanciful encounters with giants and freaks led many subsequent real explorers, including Christopher Columbus, to express surprise (and possibly disappointment) at

not

finding such extreme exotica. In chapter 31 Mandeville describes many enormous giants, some more than fifty feet tall, and then tells of an island tribe of people whose women carry venomous snakes in their vaginas. These snakes sting the penis of the man who enters, and he perishes quickly after. To ensure safe entry, newlywed grooms enlist other men as coitus “testers.” These and other such descriptions made the

Travels

one of the most widely disseminated books before the advent of printing.

The Christians were not the only ones interested in Alexander’s gates. The Qur’an itself tells a story that rehearses many of the features of the Alexander story. In the Cave chapter (“Surat al-kahf”) of the Qur’an we learn of a great king, Dhu’l-Qarneyn (He of the Two Horns), whom many secular and Islamic scholars take to be Alexander.

45

The Qur’an tells the following story of how the great king confined Gog and Magog:

Then he followed a road till, when he came between the two mountains, he found upon their hither side a folk that scarce could understand a saying. They said: O Dhu’l-Qarneyn! Lo! Gog and Magog are spoiling the land. So may we pay thee tribute on condition that thou set a barrier between us and them? He said: That wherein my Lord hath established me is better (than your tribute). Do but help me with strength (of men), I will set between you and them a bank. Give me pieces of iron—till, when he had levelled up (the gap) between the cliffs, he said: Blow!—till, when he had made it a fire, he said: Bring me molten copper to pour thereon. And (Gog and Magog) were not able to surmount, nor could they pierce (it).

46

Muslims, like everyone else, accepted the existence of barbaric races. The historian Aziz Al-Azmeh even suggests three common markers that Muslims used to diagnose foreign peoples for barbaric status; filth, profligate sexuality (ascribed to Europeans), and unholy funerary rites.

47

In principle, then, the idea of a great king shutting up dangerous uncivilized races behind an iron gate made sense, but the question was, Who were these brutes? Muslims could not and would not interpret the gates as enclosing themselves or the relatively more familiar peoples of the Eurasian steppes, nor did they believe Gog and Magog comprised the lost Jewish tribes. Islamic civilization of the time, unlike European Christendom, was simply too close to the region to accept any facile identification of the monstrous Gog and Magog. During the Patriarchal and Umayyad Caliphate expansions of Islam (632–750

CE

), for example, the territories near the legendary gates would likely have been Muslim. When, in the ninth century, Caliph al-Wathiq-Billah sent an interpreter named Sallam to find Alexander’s renowned gates, Sallam failed to discover them in the Caucasus but claimed to find them much further inside Asia.

48

This tells us something about the human tendency to keep locating barbarism and monstrosity farther and farther away from oneself and one’s own tribes. Instead of naming the ethnic groups inside Gog and Magog, Aziz Al-Azmeh claims, Arab Islamic culture left them unnameable, imaginary place-holders. These unnamed were the antithesis of civilization, and Muslims accepted the idea that their counterhumanity would strike against

pious culture once the gates were breached, but the creatures themselves were more anonymous than in the European narratives.