"Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich (77 page)

Read "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich Online

Authors: Diemut Majer

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Eastern, #Germany

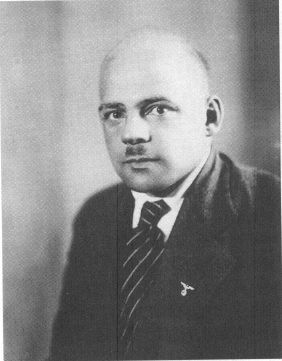

FIG. 19 Dr. Franz Schlegelberger, secretary of state in the Reich Ministry of Justice, 1933–40, acting Reich minister of justice, 1941–42, after the death of Reich Minister of Justice Dr. Franz Gürtner in January 1941. Photograph by Heinrich Hoffmann, courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München.

FIG. 20 The “

Gau

-kings” of the Reichsgaue, Erich Koch of East Prussia (

left, next to General Karl Bodenschatz of the Luftwaffe

) and Franz Schwede-Coburg of Pomerania (

right

) in discussion with Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick (

second from right

). Photograph by Heinrich Hoffmann, courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München.

FIG. 21 Fritz Sauckel, plenipotentiary general for labor allocation, who was in charge of organizing the system of forced labor in all occupied territories. Courtsey of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives.

FIG. 22 Erich Koch, Gauleiter (highest NSDAP official in a Party district) of Eastern Prussia, became Reich commissar for the Ukraine in 1941. In 1959 Koch was sentenced to death by the Polish Supreme Court. The sentence was later changed to life imprisonment. He died in a Polish prison in 1986. The picture shows him as a defendant before the Polish Supreme Court in 1946. Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie, courtesy of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives.

FIG. 23 The Reich minister and head of the Reich Chancellery, H. H. Lammers (

left

) and Secretary of State H. Stuckart of the Reich Ministry of the Interior (

right

) in discussion with Adolf Hitler (not pictured). Photograph by Heinrich Hoffmann, courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München.

FIG. 24 An execution of Polish citizens by German police forces in German-occupied Polish territory, presumably 1939. Archiwum Pa stwowe Inowrocław, 1549 Sign. 1557.

stwowe Inowrocław, 1549 Sign. 1557.

PART TWO

The Principle of Special Law against “Non-Germans” in the Field of Justice

Section One

The Implementation of Völkisch Inequality in the Altreich

A. Penal Law

I. The General Thrust of National Socialist Policy in Penal Law

In the implementation of

völkisch

inequality in the field of justice, the main emphasis was naturally on criminal law, for it is there that the mechanisms of suppression inherent in the National Socialist system were most visible and the treatment of “non-Germans” reached its peak of unbridled terror. At first, however,

völkisch

inequality—or the “special treatment” of Jews, as the terminology originally had it—could not be implemented in the Reich territory by legislative means on any great scale, except by way of exceptional measures such as the Blood Protection Law.

1

For in accordance with section 3, paragraph 1 of the Penal Code, all offenses committed by German nationals, including Jews who had German nationality (

Personalprinzip

), were to be judged by the established laws,

2

and there was great reluctance to amend this basic regulation. It was thus possible to implement special penal provisions only if in formal terms they could be encompassed within the framework of general criminal law. Therefore the name of the game was to incorporate the discriminatory intentions of the political leadership into the terms and objectives of the general criminal legislative and judicial policy, without amending the actual texts as written. Once the special criteria had become generally established, they could be “interpreted” to apply to each individual case as required. The application of such general discriminatory measures was thus effected in two stages: first through directives, recommendations, and suggestions by the judicial authorities (with no change in legislative intent); and second, in concrete cases, through extensive court interpretation of the offenses and by a harsher evaluation of culpability. It is important to bear this sequence in mind in order to understand how the treatment of “non-Germans” under special law was able to function so smoothly. We shall now review the sequence in more detail.

1. Rejection of the Established Principles of Law

It should not be forgotten that this harsher treatment of “non-Germans” was part of an overriding general trend to tighten up and extend the interpretation of criminal offenses, which included cases involving Germans. The policy of rendering criminal proceedings more stringent had already been applied by the Nazi leadership in peacetime in many ways:

3

through the enactment of a large number of new penal provisions amending the Penal Code in both content and form (especially in the field of political and so-called martial criminal law);

4

through a tightening up of the existing legislation and legal sanctions (extension of the death penalty);

5

through the introduction of the principles of public security and correction;

6

through the creation of new branches of the law with stronger powers to award punishment, such as the special courts and the People’s Court;

7

and through the abolition of procedural safeguards.

8

A reshuffling within the Reich Ministry of Justice put State Secretary Freisler, the most radical proponent of the Nazi legal policy, in charge of all the criminal and other important departments, while State Secretary Franz Schlegelberger, originally a specialist in commercial law, managed the less crucial sectors. This constellation guaranteed that the criminal procedure policy would remain extremely tough.

9

The tactic of a general tightening up of penal law and the criminalization of large segments of everyday life can be traced back to the National Socialist concept of a new penal law,

10

which it was intended to implement through extensive penal reform in the broader framework of general legal reform.

11

In this context the fulfillment of old plans for a reform of the judiciary were of major importance, and they made strange bedfellows with the Nazi ideology. The combination was not successful at all, since the Ministry of Justice was not ready to give up its traditional legal perfectionism; the conflict ultimately led to the ruin of the ministry.

12

Championed at the political level primarily by the judicial directorate of the NSDAP under Hans Frank,

13

this drive for reform picked up the strands left by the Weimar Republic, which had developed a number of texts ready for enactment,

14

thus maintaining an appearance of continuity.

15

But although the Prussian and Reich justice ministries had worked on the reform since 1933 and had presented complete draft bills,

16

it made little progress. At the May 1937 meeting of the Reich cabinet, which was to be its last, the movement was shelved once and for all, because fundamentally the political leadership was not interested in radical reform, which would have established defined legal regulations limiting the power of the state to determine the status of suspects or defendants, tying it down to rules of procedure and so on. For a regime that was characterized above all by irrationality and arbitrariness and thus needed to be constantly in movement, such reform would have meant immobility and so could not be tolerated. The political leadership had decided that the best way to achieve its aims was to alter the criminal code by the enactment of single statutes, which would follow a harsher or a more lenient line according to the political expediency of the moment, thus effectively concealing the long-term erosion and destruction of the legal regime inherited from the liberal period, the form of which remained intact.