Napoleon in Egypt (26 page)

By now the Nile waters were beginning to rise, and Desaix reported from Giza that the flooding of the banks upstream meant that it was impossible for him to mount any effective pursuit of Murad Bey immediately. Napoleon decided upon a different tack, and on August 1 dispatched the Austrian consul Carlo Rosetti to Upper Egypt to meet with Murad Bey, whom Rosetti had come to know as a personal friend during his years in Egypt. Napoleon instructed the neutral consul to negotiate a peace settlement, giving him full powers to make Murad Bey the generous offer of the governorship of Girga province in Upper Egypt if he was willing to accept French rule.

Ibrahim Bey was another matter. News soon reached Napoleon that he had halted his flight towards the safety of the Sinai desert at Bilbeis, just thirty miles northeast of Cairo. Here he had intercepted the annual pilgrimage on its return from Mecca, and plundered it of camels and provisions for his journey. Sensing his chance, Napoleon immediately dispatched Reynier after Ibrahim Bey with a hastily assembled force, including some 350 cavalry (his mounted forces now augmented with horses requisitioned in Cairo). The French infantry were reluctant, and Reynier’s progress was slow. Impatient at this news, Napoleon decided to take command himself, and quickly rode out into the field to effect more speedy progress.

Napoleon and the advance cavalry unit surprised Ibrahim Bey as he was camped in a stand of palm trees on the outskirts of El Saliyeh, at the edge of the Sinai desert; but the tables were quickly turned as the French found themselves confronted by 500 Mameluke cavalry and 500 Arab infantry. In the ensuing skirmish the French suffered thirty casualties, and Napoleon himself was saved only by the timely arrival of Reynier’s troops, whereupon the 500 Arabs switched sides, and the French at last tipped the scales. Even so, Napoleon could only watch impotently as Ibrahim Bey and his camel caravan of wives and treasures escaped into the distant desert.

Napoleon now learned from one of the Arab deserters that he had also been close to capturing Pasha Abu Bakr, who was still with Ibrahim Bey. In a switch of tactics, he immediately dispatched a conciliatory message to Ibrahim Bey, offering him peace terms: “You have been driven to the edges of Egypt and are now faced with the prospect of crossing the desert. You will find in my great generosity the good fortune and happiness that will transform your present circumstances. Let me know soon of your intentions. The Pasha of the Turkish Sultan is with you: send him to me with your reply. I willingly accept him as a go-between.”

5

Ibrahim Bey was not for one moment deceived by Napoleon. He had no intention of sending Abu Bakr as an intermediary—whereupon he would certainly have been detained by Napoleon, who would have used him to validate his claims of legitimacy with the Porte. Napoleon now sent out patrols to make contact with the scattered remnants of the caravan from Mecca, which he ordered to be escorted to Cairo under armed French protection.

Napoleon remained for two days at El Saliyeh, organizing the French administration of the delta. By now Vial had taken Damietta, where he was established as governor; Reynier was appointed governor of the eastern delta region at Bilbeis; and Murat became governor at Qalyub, in the delta region north of Cairo. Each military governor was ordered to establish a provincial

divan

, its members drawn from amongst local sheiks and

ulema

, which was to deal with the everyday running of their district. Although this was hardly democracy, any more than it represented a truly liberated Egypt, it is worth noting that it was the nearest thing to popular rule the country had experienced throughout its five millennia of history.

On August 13 Napoleon set off back for Cairo. Before he reached Bilbeis he was met by a military courier who had left Alexandria thirteen days previously, but whose speed had been hampered by his need for a military escort through the countryside of the delta, which remained treacherous. The courier delivered to Napoleon some catastrophic news which would transform his entire Egyptian expedition.

X

The Battle of the Nile

A

FTER

sailing from Alexandria on June 29, Nelson’s squadron had set off north in search of Napoleon’s expeditionary armada. Although Nelson had mentioned to his officers the possibility that he had arrived ahead of Napoleon, in his agitation he chose to forget this: evidently Napoleon’s destination had not been Egypt after all. Nelson now surmised that the French fleet was in fact heading for Turkey, but after five days’ sailing he changed his mind again and turned west. By now, the heady atmosphere which had enthused the squadron during its chase to Alexandria had entirely dissipated, and an air of despondency prevailed—especially amongst the officers on board the

Vanguard

, Nelson’s flagship, where alcohol began to flow more freely over the dinner table. Records show that during the first week in July alcohol consumption peaked, with Nelson, his captain and his dozen or so officers managing to get through twelve bottles of port, nine of sherry, six of claret and twenty of porter (and this does not include the private stocks which most officers maintained for their own personal consumption on board).

1

Turning west off Cyprus, Nelson began zigzagging his way under the lee of Crete, up the Mediterranean, in the hope of catching sight of the French fleet, but to no avail. The horizon remained empty. They were off the main shipping routes, and there wasn’t even the occasional passing merchantman to give them any news: the huge French fleet had seemingly vanished. Nelson remained perplexed, at the same time showing increasing signs of anxiety, summoning his captains to frequent meetings aboard the

Vanguard

, at which they would again and again fruitlessly discuss all likely possibilities. After Napoleon had taken Malta, had he sailed north to take Sicily? Or worse still, had he headed west for the Atlantic, where he might by now be mounting an invasion of England, or Ireland, or even Brazil? Once again Nelson’s nerves appeared at breaking point. After nearly three weeks’ sailing, the British squadron of thirteen ships of the line arrived off Sicily, putting into Syracuse on July 20. The local populace lined the quayside to gaze at the British fleet, as the first longboat was rowed ashore. Nelson learned that Napoleon had not invaded Sicily, and also received news that he had not sailed west for Gibraltar either. The French were still somewhere in the Mediterranean.

Nelson remained four days in Syracuse, taking on supplies. Limited shore leave, together with fresh provisions—including vegetables, lemons, haunches of beef, and 100-gallon butts filled with water from the legendary Fountain of Arethusa—bolstered the morale of the squadron, and on July 23 Nelson noted, “The fleet is unmoored, and the moment the wind comes off the land, shall go out.”

2

The offshore evening breeze filled the slack sails of the British ships of the line, and Nelson’s squadron headed once more for the eastern Mediterranean. He still had no clear idea what to do, but prior to departing he had left a message for dispatch to his superior, Admiral St. Vincent, off Cadiz: “It is my intention to get into the mouth of the Archipelago [Aegean Islands], where, if the enemy are gone towards Constantinople, we shall hear of them directly: if I get no information there, to go to Cyprus, when, if they are in Syria or Egypt, I must hear of them.”

3

These words show all the signs of being written in hope rather than expectation: evidence with which to defend himself before the expected Admiralty inquiry. But then Nelson had a lucky break: after five days’ sailing he found himself off Coroni, at the southwest tip of the Greek Peloponnese, where he dispatched ashore Captain Troubridge on the

Culloden

to seek out any local intelligence. Here Troubridge heard that the local Turkish governor had been informed by the Porte in Constantinople that Napoleon had invaded Egypt. This news was confirmed with the capture of a French brig bound for Egypt loaded with wine, which was taken in tow by the

Culloden

.

Nelson at once set sail, though he remained uncertain of what to do when he arrived; Napoleon’s fleet would doubtless be safely moored in harbor, well out of harm’s way. All he could do was blockade the French, until such time as his shipboard supplies ran low and he was forced to leave. Meanwhile Napoleon would probably be well on his way to India. Nelson knew that in the eyes of the Admiralty his initial blunder was only liable to be compounded by further ineffective action, such as a temporary blockade. But what else could he do? It now looked as if he would be held responsible for the loss of the British Empire’s most valuable possession, no less.

On the morning of August 1, the

Alexander

and the

Swiftsure

, sent ahead by Nelson, appeared off Alexandria. Observing through their telescopes, the British made out the French tricolors flying from the forts and towers. In the port there were all kinds of craft, including two French ships of the line and several frigates, but no sign of the main French battle fleet, and this news was duly signaled back to Nelson. The

Zealous

and the

Goliath

were dispatched on a search east along the coast. Eight miles down the coast, at two-thirty

P.M.

, the masthead lookout on the

Zealous

spotted, beyond the curving sand spit which protected Aboukir Bay, a forest of masts: the French fleet was lying at anchor in the bay. At two-forty-five, Captain Hood aboard the

Zealous

signaled by flags, “Sixteen sail of the line at anchor, bearing East by South.”

4

The news was greeted by a burst of cheering from the British sailors, which soon began resounding from ship to ship around the squadron.

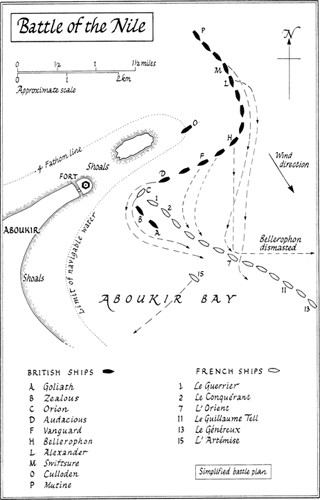

Aboukir Bay lay at one of the ancient mouths of the Nile, which had long since silted up. It provided a fine anchorage, its vast sweep protected by a peninsula, with a fort at its end, as well as shoals and a rocky islet beyond. Inside the peninsula and islet were further shoals and shallows, close to which the French fleet was anchored in line. It consisted of thirteen

*

ships of the line, their strongest guns mounted on their offshore side—a classic defensive position—with the French flagship

L’Orient

anchored in the middle of the line. The British squadron still did not quite match the French, especially in gunpower, and if it went on the attack it would have to sail towards a line of enemy ships with over 500 guns mounted to starboard, with the French crews having nothing else to do but concentrate upon firing these guns. Meanwhile the British sailors would have to sail their ships as well, while they maneuvered themselves into a position where they could fire at the enemy. And even then they would only be able to fire half their guns—those mounted on the side facing the French fleet.

When the British sails had first been sighted by the lookouts of the French fleet at around two

P.M.

, many crew members had been ashore digging wells in the sand for fresh water, together with their armed escorts, to guard against the hostile Bedouin who roamed the dunes. Alarm flags were raised on the masts of the French fleet, and the men ashore began making their way back to the boats, but with no particular urgency: the source of the alarm, the British sails approaching from the horizon, remained blocked from their view by the peninsula. The men began rowing the three miles from the beach across the shallows to the line of French warships swinging at anchor. Even when these crews were on board, many of the French ships remained undermanned, as several hundred men had been sent with the available sloops to Alexandria and Rosetta to bring back spare rigging, together with much-needed supplies of rice, beans and vegetables.

It has been estimated that some ships of the French fleet may have been lacking as many as a third of their crew; and even those on board were not exactly battle-hardened sailors. In the rush to crew up the French fleet at Toulon, all manner of local fishermen, dockside loafers, and even jailbirds had been press-ganged to make up the numbers. In consequence, much of the French fleet was manned by an undisciplined rabble. (As governor of Alexandria, Kléber had already had cause to order all shore leave canceled after several incidents between sailors and the locals. Napoleon’s strict orders to his men concerning conduct towards the Egyptians had been ignored by the sailors, who as naval men did not consider themselves bound by army orders.)

From the quarterdeck of

L’Orient

, Vice-Admiral Brueys gazed through his telescope at the approaching British sails. By four

P.M.

, as the shadows started to lengthen, the British ships of the line were still making their way along the coast in a following wind in no particular formation, spread over miles. It appeared that they would take up their battle stations when they anchored for the night, in preparation for an attack on a morning onshore breeze. Only gradually did it become clear to Brueys that the British seemed intent upon an immediate attack. He could hardly believe his eyes: they would be sailing in failing light into shallow waters for which they had no charts, and as darkness fell during the engagement they would be liable to mistake their own ships for the enemy.