Napoleon in Egypt (11 page)

As soon as Nelson received his reinforcements and new orders, he set sail on June 8 from his station off Toulon, following what he rightly assumed had been the French fleet’s course east and then southwards along the Italian coast, all the time trying to work out Napoleon’s likely route and intentions. By June 15 he was writing to First Sea Lord Spencer: “The last account I had of the French fleet was from a Tunisian cruiser, who saw them on the 4th, off Trapani, in Sicily, steering to the eastward. If they pass Sicily, I shall believe they are going on their scheme of possessing Alexandria, and getting troops to India—a plan concerted with Tippoo Saib [

sic

], by no means so difficult as might at first view be imagined.”

13

Imagined by Nelson, that is. Ironically, whereas Napoleon planned to march in Alexander the Great’s footsteps across 3,000 miles of desert and hostile territory, Nelson envisioned a far more practical and well-organized scheme. He assumed that Napoleon had already sent French ships ahead, around the Cape of Good Hope, which would arrive at Suez and then ferry his army to India. He was not to know that Napoleon’s plans, executed in haste and inspired by glory, remained lacking in such practicalities.

Two days later, on June 17, Nelson and his squadron arrived off the Bay of Naples, where he sent inquiries to his friend the British ambassador Sir William Hamilton and his wife Emma, and picked up word that the French fleet had been sighted on June 8 off Malta, seemingly on the point of invading the island. Nelson at once set off on the 400-mile voyage through the Straits of Messina, at the same time working out the tactics he would employ if he encountered the French fleet. He decided that he would split his squadron into three: two groups would engage the French battleships, whilst the third would do its utmost to destroy as many of the French transports as possible. Had this happened, it could well have resulted in sprigs of cypress for Nelson rather than the laurel wreath he coveted. The first two groups would have been outgunned by the French, and the French transports would certainly have scattered, making it difficult for Nelson’s few chasing ships to destroy a significant number. However, although Nelson’s quixotic bravery might well have resulted in his own destruction, and that of his entire squadron, it would probably have wreaked sufficient damage and dispersal to have put an end to any immediate French invasion of Egypt. Nelson’s estimate of the situation may have been reckless, but it was certainly closer to effective reality than that of Napoleon, who would later declare: “If the English had really wanted to attack us during the voyage we should have easily beaten them.”

14

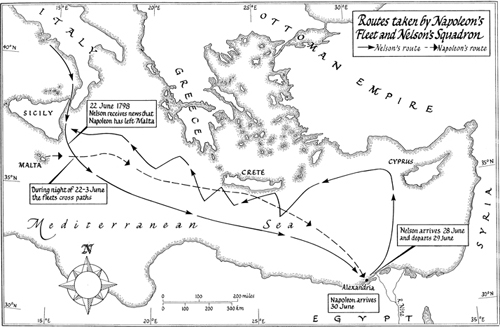

More pertinently, Nelson reasoned that if after leaving Malta the French fleet sailed north, it would be to invade Sicily; if it sailed east, it would be heading for Alexandria. And early on June 22, as Nelson was sailing past Cape Passaro, the southeastern tip of Sicily, he received the news he had been waiting for. His squadron encountered a Genoese merchantman which informed them that the French had conquered Malta on June 15 and departed the next day, sailing in an easterly direction. Napoleon was definitely bound for Alexandria. Nelson set off in hot pursuit.

It is no exaggeration to say that had this information, shouted early one summer’s morning from one passing ship to another off a lonely Mediterranean cape, proved correct, it would have changed the course of world history. Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt would probably have been thwarted, leaving his career in ruins. But the voice calling across the water from the Genoese merchantman had been misinformed. In fact, Napoleon had only set sail from Malta on June 19, but Nelson, under the misapprehension that the French had six days’ start on him, now turned his squadron east on a direct course for Alexandria, making haste with all sail. Later that same day the weather became misty and the blurred shapes of what appeared to be three frigates appeared in the distance. Nelson ordered the brig

Mutine

to investigate, and when it returned at dusk its captain reported that he had identified the three as French. Nelson decided to allow the ships to disappear into the misty darkness; he reasoned that he could not afford to split his squadron on a wild goose chase after three lone frigates. His objective was the entire French fleet, which he calculated was by now several hundred miles to the southeast.

Nelson’s decision proved an unfortunate and colossal blunder. The three French frigates were in fact the outriders of the French fleet, which lay just over the horizon, having left Malta only three days previously, traveling in a northeasterly direction towards Crete. And so, during the misty night of June 22/23, the paths of the two fleets actually crossed within a few miles of each other, the French listening in silence as the guns of Nelson’s squadron boomed dully through the pitch darkness at regular intervals.

*

Next morning, as dawn broke, the two fleets each found themselves surrounded by an empty horizon: their courses had crossed and they were now divergent, Nelson bound southeast direct for Alexandria in pursuit of a chimera, Napoleon bound northeast for Crete on his odyssey in pursuit of destiny.

Making over a hundred miles a day, Nelson managed to reach Alexandria in just six days. To his consternation, he found no sign of the French fleet. He dispatched Captain Hardy aboard the brig

Mutine

ashore for intelligence: in the harbor was just one ancient Turkish warship, and a few merchant vessels. Amongst the curious Egyptian spectators drawn to the quayside there were no French uniforms or any suggestion of an invading army. The local

sherif

knew of no French fleet.

Nelson was plunged into despair. In his extremity he would shift the responsibility for his failure to the inadequacies of his squadron: “I have again to deeply blame my want of frigates, to which I shall ever attribute my ignorance of the situation of the French fleet,”

15

he wrote back to his immediate superior, Admiral St. Vincent, who had placed so much trust in him. Nelson had no idea where the French fleet could be. Had it sailed north to invade Sicily after all? Or, worse still, had it headed west for the Straits of Gibraltar, to join up with the French Atlantic fleet for an invasion of England or Ireland? These questions would, over the following days, bring Nelson to the brink of a nervous break down. He had blundered badly, and he knew it. When the news of his failure reached London, it was greeted with outrage. In Parliament it was denounced by the future cabinet minister George Rose as “the most extraordinary instance of the kind I believe in the Naval History of the World.”

16

The newspapers soon took up the chorus of disbelief, one declaring: “It is a remarkable circumstance that a fleet of nearly 400 sail, covering a space of so many leagues, should have been able to elude the knowledge of our fleet for such a long space of time.”

17

After waiting just twenty-four hours off Alexandria, Nelson set sail north on the morning of June 29.

V

“A conquest which will change the world”

A

T

dawn on the very morning that Nelson’s squadron set off north, the French frigate

La Junon

, sailing ahead of the French fleet, caught its first sight of the African shoreline. Astonishingly, neither

La Junon

nor Nelson’s squadron noticed one another. Almost equally astonishingly, Napoleon’s cumbersome fleet had covered a greater distance than Nelson’s squadron and had taken only a couple of days longer.

La Junon

had been sent ahead to reconnoiter the coast and pick up the French consul in Alexandria, so that he could apprise Napoleon of the situation. The report from consul Magallon made for uncomfortable listening. Nelson’s emissary ashore, Captain Hardy, had informed the

sherif

of Alexandria, Mohammed El-Koraïm, that he was in pursuit of a large French fleet which was intending to invade Egypt. According to the chronicle of events written by Nicolas Turc, a poet of Greek extraction who was living in Egypt at the time, El-Koraïm had been frankly distrustful of the British. “It is not possible that the French are thinking of coming to our country. What would they do here?” he demanded. He had denied the British permission to put ashore for fresh water and victualing, adding: “If the French arrive here with hostile intentions, it will be for us to see them off.”

1

In fact, El-Koraïm’s answer was certainly disingenuous. The Egyptians had initially mistaken Nelson’s ships for a French fleet; as it happened, they were already expecting the French. But how could they possibly have been aware that the French were planning to invade Egypt? Some suggest that El-Koraïm had been informed by a merchantman from Malta about Napoleon’s occupation of the island, and that he had guessed the next target would be Egypt. Napoleon had put an embargo upon any ships leaving Malta during his occupation, yet news of his invasion had certainly spread, if only in inexact form—witness what Nelson had learned from the Genoese merchantman off Sicily. However, much more likely is that El-Koraïm and the Egyptian authorities had already received official word from the Porte in Constantinople warning of a French invasion. Although Napoleon’s destination had remained a tightly kept secret, with even the British only picking up the vaguest of rumors, the Porte had learned that the French intended to invade Egypt almost as soon as the decision had been taken. Greek intelligence agents working for the Turkish embassy in Paris had discovered the truth as early as March, the very month in which the Directory had initially sanctioned Napoleon’s idea. This news had been conveyed speedily over land to Constantinople, and in April the Turkish ambassador in Paris had received instructions to confront Talleyrand, demanding to know if the French fleet being assembled at Toulon was in fact preparing to invade Egypt. Talleyrand had remained his inscrutable, imperturbable self, pointing out that the French were close allies of the Porte, and as such could not possibly have aggressive intentions towards any territory under direct Turkish rule, a slippery answer which gave him sufficient space to maneuver. Whether Egypt was under

direct

Turkish rule was an open question—a point recognized at once by the Turkish ambassador. Typically, Talleyrand decided not to pass on to Napoleon the full details of this diplomatic encounter, which certainly failed to convince the Porte. News of French intentions was probably conveyed to Egypt at least by early June, doubtless causing some consternation. Even so, as we shall see, there is abundant evidence that nothing much was done about this, and the matter appears to have been forgotten. The arrival of Nelson’s squadron had jolted it back into mind. Even so, El-Koraïm appears to have been reassured by Nelson’s willingness to depart, for he still undertook very little in the way of defensive preparations.

The French consul ended his report to Napoleon by revealing that Captain Hardy had delivered a secret note to the British representative, with instructions that this be conveyed forthwith via Suez to India. Napoleon now knew that Nelson’s squadron was in close proximity and searching for him, and that the Egyptians were forewarned of the French arrival. He also knew that his dream of creating an Eastern empire, dismissed by so many as fantasy, had been taken seriously at least by Nelson. His bold strike in the footsteps of Alexander would be lacking the element of surprise: the British would be waiting for him.

As if all this potentially disastrous news was not bad enough, a strong northeasterly wind had now begun to blow, and was soon whipping up the waves and driving the fleet towards the shore. In the words of the savant Denon, who was present at the meeting between the French consul and Napoleon: “The English could have arrived at any instant. The wind was so strong that the warships were becoming mixed up with the transport convoy, and amidst the confusion we would have been assured of the most disastrous defeat if the enemy had appeared.” Despite everything, Napoleon remained unmoved, and when the consul had finished his report, Denon observed: “I was not able to detect the slightest expression on his features, and after several minutes of silence he ordered the disembarkation to begin.”

2

Napoleon had decided against any disadvantageous landing amidst the shallows and enclosed harbors of Alexandria, in case he faced determined resistance. Instead he chose to land at the fishing village of Marabout, some five miles west of Alexandria. Owing to the under water reefs along this part of the coast, it was not possible to stage a widespread simultaneous landing, so the disembarkation was limited to a narrow stretch of coastline and thus likely to take at least three days. Vice-Admiral Brueys immediately protested in the strongest possible terms: attempting even a limited landing amidst shoals in such weather was far too dangerous. Napoleon refused to argue: “Admiral, we have no time to lose. Fortune has given me three days, if we do not take advantage of this we are lost.”

3