Napoleon in Egypt (23 page)

During the following days, four of the French divisions began crossing the Nile, guarded by Desaix’s division upstream. On July 24 Napoleon himself crossed the river and reviewed before the walls of Cairo those men of the four divisions who were already across. Before them was drawn up a delegation of sheiks and

ulema

offering the keys to the gates of the city in an act of symbolic submission. After a short ceremony the trumpets sounded a fanfare, there was a roll of drums, and Napoleon rode into the city at the head of a column of grenadiers. This time the streets were lined with spectators, all curious to catch a glimpse of the infidel conqueror.

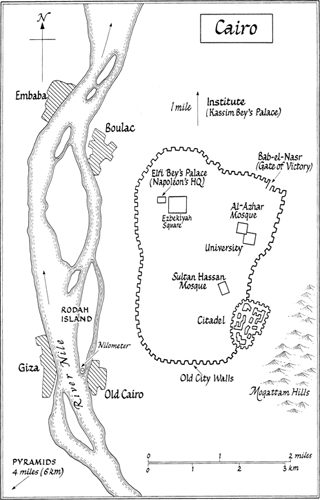

Napoleon established his headquarters in the deserted palace of Elfi Bey on the northwestern edge of the city. This was in fact the most modern and luxurious residence in Cairo, having been recently completed at great expense for its powerful owner, who had long been a favorite of Murad Bey, and who had fled with his master into Upper Egypt. Elfi Bey’s palace was set amidst extensive beautiful gardens with cypress and orange trees. Its grand front terrace, complete with marble pillars and polished Aswan granite floor, looked out over the large open park known as Ezbekiyah Square, which for part of the year was flooded by the waters of the Nile and became a lake. The front hall of the palace contained a large ornamental fountain and each of its main rooms was decorated in lavish style, with gilt mirrors, damask curtains and silkwoven Persian carpets, as well as divans and sofas. Unusually for a Mameluke palace, it also had chairs, and sunken baths on both floors.

*

Cairo was during this period regarded as the second city of the Ottoman Empire; its permanent population consisted of an estimated 500,000 inhabitants (almost a fifth of the Egyptian population), making it larger than Paris. It was a renowned trading center, with large seasonal caravans, consisting of hundreds of camels, arriving from as far afield as Aleppo, Mecca, Darfur in the Sudan, and Timbuktu 2,000 miles away on the other side of the Sahara. Within the precincts of Cairo there were more than 300 mosques, from whose minarets the voices of the muezzins would ring out over the rooftops of the city day and night with the regular calls to prayer. The post of muezzin was traditionally occupied by blind men, allegedly so that when they looked down from the minarets they could not see into the exposed private rooms of the houses below. Whether or not this was the case, the muezzins in Cairo would have seen little at certain times of day, when the atmosphere was blighted by a pall of brown smog from the household cooking fires, many of which used dried dung for fuel. They would also have needed strong voices, to make themselves heard over the barking of the rabid dogs which roamed the alleyways in packs; these were liable to break into a cacophonous racket at the slightest disturbance, in the process setting off any other dogs in the vicinity. It was said that throughout the country the number of wild dogs may well have outnumbered the population of Egyptians, which had sunk to just two and a half million, a third of its size at the height of pharaonic times over three millennia previously.

Many of Napoleon’s generals were billeted in deserted Mameluke palaces, and even the leading savants Monge and Berthollet took up residence in a fine mansion on Ezbekiyah Square. Other officers, as well as the men, had to make do with lesser accommodation throughout the city, with the soldiers often camping out in courtyards. Up until now, most members of the French expeditionary force had barely come into contact with the indigenous population; and when first they ventured beyond the walls of their billets into the teeming streets of Cairo, they were in for a deep culture shock. The reaction of Major Detroye of the engineers is typical, infused as it is with the prejudices of his race and era:

On entering Cairo, what do you find? Narrow streets, unpaved and filthy, shadowy houses often in ruins, even the public buildings seem like dungeons, shops are nothing better than stables, the air is filled with dust and the reek of garbage. You see men with one milky eye, others totally blind, men in beards, clothed in rags, swarming through crowded alleyways, or smoking pipes, squatting like monkeys before the entrance to their caves. And as for the women—nature’s masterpiece elsewhere in the world—here they are hideous and revolting, hiding their emaciated faces behind reeking threadbare veils, their naked pendulous breasts showing through their torn robes, their children yellow and skinny, covered in suppurating sores, surrounded by flies. Hideous smells come from the filthy interiors, and you choke on the risen dust together with the odor of food being fried in rancid oil in stuffy bazaars.

4

After his “sightseeing tour,” Detroye would return to his Cairo abode, which was evidently not in one of the Mameluke palaces:

A place devoid of human comforts, or proper living space. The flies, the midges, a thousand insects of all sorts, waiting to pounce on you in the night. Soaked in sweat, prostrate with exhaustion, instead of resting you spend the time boiling and itching. In the morning you get up in a foul temper, your eyes swollen, sick in your stomach, your skin covered in bites which have by now been scratched septic. And so another day begins, no different from the last.

5

Memoir after memoir lists the complaints of the occupying soldiers in these unfamiliar surroundings far from home. But reactions were not always entirely negative: young Captain Malus, with exemplary pragmatism, commented, “In the face of all this, one realized that it was necessary to renounce our European behavior, and to behave as they did. Unfortunately, during the first days we experienced all that was despicable in their Turkish [

sic

] behavior and none of the delights.”

6

Surprisingly, it was the aging artist Denon who was the first to discover these delights, though even he was not totally enamored. He watched some belly dancers performing, accompanied by two male musicians on accordion and hand-drum, and some singers with tinkling finger-cymbals. Of the dancers he commented:

The way in which they twist their bodies lends an infinite grace to the movements of their wrists and fingers. At first their dancing appears beautifully voluptuous, but it soon descends into lasciviousness, becoming no more than the expression of a crude and indecent sensuality, and what is most disgusting about the show is that even when the dancers are performing with delicacy and restraint, one of the musicians will begin leering like a coarse buffoon, turning the whole thing into a drunken debacle.

7

Denon noticed that these women

drank the local firewater in big glasses as if it was lemonade, so that although they might have been young and pretty they soon became tired and withered, except for two whose beauty and manner were as striking as any two famous beauties in Paris, their purely natural grace suggestive of the caresses and sweet voluptuousness that they doubtless reserved for those upon whom they lavished their intimate favors.

8

The Egyptian reaction to the French occupation was similarly double-edged. El-Djabarti records his wonder at the soldiers “walking about the streets of the city unarmed and not molesting anyone. They joked with our people and in the bazaars bought whatever they wanted. . . .They went on buying bread, no matter how high the prices rose. The bakers, to increase their profits, reduced the size of their loaves and mixed in dust with the flour.”

9

More perceptively, Nicolas Turc noted how the French “easily pardoned their enemies, showing themselves open and indulgent, observing justice, making good rules and passing good laws. However, in spite of all these efforts, they were not able to win over the hearts of the people. The Muslims hid their hatred for these people.”

10

Despite such ambiguities, the truth of the situation was simple enough. For all the good- and ill-will, these two so different people were divided by a gulf of incomprehension. And nowhere was this more apparent than in the

divan

which Napoleon set up to rule Cairo. This was established on the day after his entry into the city, and consisted of nine sheiks, with a French commissioner appointed to sit in on the proceedings, and two Arabic-speaking savants to translate for him. The

divan

was to meet every day, and was expected to ensure the smooth running of the city in matters ranging from policing to the burial of the dead. The first French commissioner appointed to the

divan

was Poussielgue, Napoleon’s former financial administrator and spy, who was expected to advise the members when necessary and to report back to his commander-in-chief on the day’s proceedings.

From the outset, there was to be no meeting of minds here. Napoleon’s covert intention was clear, as he later confided in a long letter to Kléber in Alexandria: “By winning over the opinions of the leading sheiks of Cairo, one has the support of all the people of Egypt and any chieftains these people might have. None are less dangerous to us than the sheiks, who are timid, have no idea how to fight, and like all priests inspire fanaticism without being fanatics themselves.”

11

The sheiks for their part resisted all attempts to make them take any responsibility for administering the city. This was in part because they feared the return of the Mamelukes and the reprisals which might then take place; worse still, the sheiks suspected that they would be made responsible for the arrest of the remaining Mamelukes who were known to be still in hiding in the city. However, there was a deeper problem than this: the sheiks simply did not understand either the concept or the function of such a ruling council. The power of any previous

divan

had been severely limited. Egypt had for so long been ruled on the whim of the autocratic Mameluke beys that the give and take of discussion was unknown to the sheiks. When the Cairo

divan

was inaugurated under French rule, no sheik had any intention of revealing his ideas about administrative matters, let alone discussing them. One by one they insisted to Poussielgue that such decisions as he required of them should be referred to the Mamelukes or the Turks, not themselves. When Poussielgue said that this was no longer the case, the sheiks persisted in the view that such matters were nothing to do with them, pointing out that they were in fact the province of the government—it did not occur to them that this was precisely what

they

were meant to be! Even if this was not in reality fully the case, Napoleon had at least intended that the

divan

should be a conduit for public opinion. At best it would enable the French to act in concert with the wishes of the Egyptian people; it would play its part in initiating popular rule throughout the country, under the benign progressive ideas of the French. Yet here lay the deepest misunderstanding of all: there was no such thing as collective public opinion in a country which had no notion of the concept of democracy, amongst a people who had for centuries been deprived of any liberty whatsoever. The only collective public inclination—hardly a debatable opinion—was an instinctive suspicion, or worse, of all foreigners and infidels, a reservoir of ill-will whose potential was just waiting to be exploited.

The

divan

continued to meet on a daily basis, and its proceedings were duly reported to Napoleon, but nothing of any consequence was decided. The ruling of the city thus remained in the hands of Dupuy, who proceeded as best he could to administer Napoleon’s wishes in consultation with the expert local advice of Magallon and Bardeuf, who drew on their knowledge as long-term residents. Magallon suggested that the policing of the city was best placed in the hands of a European resident of Cairo called Barthelemy. According to El-Djabarti, Barthelemy was “a Greek Christian of the lowest class” whom the Egyptians called “Fart-el-Roumman, or grenadine pip”

12

—the former said to be an Egyptian onomatopoeic rendering of Barthelemy, rather than an insult, though the latter was definitely intended as such, its sense being akin to “pipsqueak.” Barthelemy was in essence a colorful, unscrupulous adventurer: a market-place bully with an overbearing demeanor, who was known for his flamboyant appearance, habitually dressed in a large white turban and traditional gold-embroidered Greek costume, with baggy trousers and a scarlet sash around his waist. He took to his new responsibilities with characteristic panache, immediately recruiting a troop of around 100 low-life Greek and Moorish cronies as his fellow police officers, and requisitioning a Mameluke palace as his headquarters, at the same time appropriating the former occupier’s harem and slaves.