Nabokov in America (20 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

He had studied America casually, beginning long before he arrived.

‖

At Wilson’s urging, he read authors who had escaped his notice, such as

Henry James (finding him to be a “

pale porpoise

61

” who needed debunking). He was

conversant with

62

Poe, Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Frost, Eliot, Pound, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Hemingway, and many others, despite being a professor largely of Russian literature and language. Nonliterary evidence also started piling up. In a poem he wrote after an overnight stay at Wilson’s, he showed an instinct for the American surreal:

Keep it Kold

63

, says a poster in passing, and lo,

loads,

of bright fruit, and a ham, and some chocolate cream,

and three bottles of milk, all contained in the gleam

of that wide-open white

god, the pride and delight

of starry-eyed couples in dream kitchenettes.

His literary path—until

Lolita

—looked promising without being especially American. Wilson had fashioned an arrangement for him at the

New Yorker

, which guaranteed him a yearly advance in exchange for first look at whatever he wrote, and what he wrote was mainly Russian-inflected. He might have made a small, smart career in

ancien régime

nostalgia, and to a degree the career he did make looks back, revives, lovingly reworks Pushkin, Gogol, and the other Russian forefathers.

He had “a vagabond’s

sharp-sightedness

64

,” however. Thomas Mann, another writer who fled Europe and became American, and who wrote prolifically while in the United States, gave scarcely a hint of his residence in Pacific Palisades, California, and before that in Princeton, New Jersey. Mann wrote about German fascism, about a fictional German composer, about the Ten Commandments and Pope Gregory of the sixth century while in America, but he did not find a way or did not seek a way to

represent his American surroundings

65

. Probably the émigré novelist who most closely resembles Nabokov in going American is

Ayn Rand

66

, his near contemporary (1905–1982), of a Jewish family similar to Véra Slonim’s, a writer of different attainments but, like Nabokov, determined to write for the movies and in the fifties the author of a giant bestseller (

Atlas Shrugged

). Rand was also from St. Petersburg, had also fled the Revolution, and her arrival in the United States began a period of intense self-education and a wholesale embrace of what she took for Americanism.

Nabokov’s first short story set in America, “Time and Ebb,” looks at the decade of the forties from eighty years later. An old man recalls the

quaint artifacts of 1944—skyscrapers, soda jerks, airplanes—and speaks to the reader in stiff, fudgy sentences:

I am also old

67

enough to remember the coach trains: as a babe I worshipped them; as a boy I turned away to improved editions of speed… . Their hue might have passed for the ripeness of distance, for a blending succession of conquered miles, had it not surrendered its plum-bloom to the action of coal dust so as to match the walls of workshops and slums which preceded a city as inevitably as a rule of grammar and a blot precede the acquisition of conventional knowledge. Dwarf dunce caps were stored at one end of the car and could flabbily cup (with the transmission of a diaphanous chill to the fingers) the grottolike water of an obedient little fountain which reared its head at one’s touch.

The nostalgia has a labored, self-pleased quality. Nabokov’s model might have been H. G. Wells, one of his favorite writers as a boy, or Frederick Lewis Allen, author of the bestselling

Only Yesterday

(1931), a spry history of the twenties. “Oh—he means those conical little paper cups they have,” a reader thinks after decoding the sprung last sentence, and the living detail of “diaphanous chill to the fingers” and “flabbily cup” goes half-astray, being too much worked for.

The story communicates a fondness for American things. In America, “my most sacred dreams have been realized,” he wrote his sister in ’45. “My family life is completely cloudless. I love this country and dearly want to bring you over. Alongside lapses into wild vulgarity there are heights here where one can have

marvelous picnics

68

with friends who ‘understand.’ ” The American turn was for him a turn of the heart. He wanted his sister and her son to be here, too, despite the vulgarity. Like Mann walking his poodle in Palisades Park, Santa Monica, beguiled by the California light, Nabokov felt safe, he felt hopeful, and in the period of this gladness he conceived

Lolita

.

*

Nicolas Nabokov’s ardent search for the American musical real resembles cousin Vladimir’s bewitchment by unique sites and specimens of lepidoptera, but the most systematic and profound seeker of meaning in American materials whose surname happens to be Nabokov is probably Nicolas’s second son, Peter, now an emeritus professor of anthropology at UCLA. Peter is the co-author of

Native American Architecture

, an indispensable photographic compendium and scholarly commentary, and author of

A Forest of Time: American Indian Ways of History

and

Where the Lightning Strikes: The Lives of American Indian Sacred Places

, among other titles. A relentless close noticer, P. Nabokov traveled the continent for decades in a style not so different from Vladimir’s—both were gripped by lifelong intellectual obsessions that brought them constantly into the outdoors, that made them expert field researchers and led them to significant discoveries. Peter Nabokov’s most approachable work is probably

Restoring a Presence: American Indians and Yellowstone National Park

(2004), co-written with Lawrence Loendorf, which briskly overturns the idea that Yellowstone was a natural preserve full of buffalo, bear, and other iconic fauna but devoid of humans. Native peoples were said to have feared the area and to have avoided it; in fact, tribal groups swept through and dwelt within what are now park lands in nonstop migrations over at least eight thousand years.

†

Wilson wrote well about Pushkin before he knew Nabokov. Clive James, the Australian-born critic, calls Wilson’s 1937 essay “In Honor of Pushkin” the best short introduction to the poet, echoing the judgment of John Bayley, author of the authoritative

Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary

. To round out the back-patting, James calls Bayley’s praise of Wilson’s short study “a generous tribute, considering that Bayley has written the best long one.”

‡

Wilson had sent Nabokov his new book

Note-books of Night

(1942), which contained “At Laurelwood,” about his New Jersey childhood.

DBDV

, 237n5.

§

From the Latin meaning “little girl,” after

puellus

, a contraction of

puerulus

, meaning “young boy, slave.”

‖

Nabokov was not yet married to Véra Slonim when he first proposed that they move to America (letter of December 3, 1923). In his late sixties, when an interviewer asked him why he had started writing in English, since he could not possibly have known that he would one day be allowed to emigrate, he said, “Oh, I did know I would eventually land in America.”

As

Nabokov began work,

Wilson sent him

1

the sixth volume of Havelock Ellis’s

Studies in the Psychology of Sex

in its French edition, drawing his attention to an appendix, the sexual confession of a Ukrainian man born around 1870.

Of a wealthy family and educated abroad, the man had been initiated into sex at age twelve. He’d become obsessively sexual and failed at his studies, and only by becoming celibate did he manage to qualify as an engineer. On the eve of his marriage to an Italian woman, he encountered some child prostitutes and succumbed to his former obsession. Thereafter he squandered all his money, the marriage fell through, and he became an addict of sex with young girls, exposing himself to them in public. The confession ends with a feeling of hopelessness, of a life ruined by a hunger beyond control

2

.

Nabokov wrote back, “

Many thanks

3

for the books. I enjoyed the Russian’s love-life hugely. It is wonderfully funny. As a boy, he seems to have been quite extraordinarily lucky in coming across [willing] girls… . The end is rather bathetic.”

He might have been in that state where everything comes as grist to the mill, the novel in his head finding reflections everywhere. His commitment to writing a sex narrative—a sex narrative likely to invite prosecution for obscenity, as Wilson’s

Memoirs of Hecate County

had done for him—seems already quite strong. The tone of his response to Wilson is also notable: his play-it-for-wisecracks approach is already in place, and the critique of his novel that would dominate public discussion—that such compassion as it displays is thin or misplaced, is afforded the degenerate Humbert as much as the ruined little girl—seems implicit.

Nabokov’s

life in Cambridge was socially rich. He had literary friends, people from Harvard and Wellesley, as well as fellow “sufferers” from the need to chase and study insects. One of

his entomology friends

4

was the son of the Harvard museum curator of mollusks; Nabokov had been corresponding with the young man, who was interested in the Blues, since ’43. Another young scientist, Charles L. Remington, began haunting the MCZ as soon as he got out of the Army, and he would soon cofound the Lepidopterists’ Society, of which Nabokov became a member. Midsummer ’46,

Remington wrote him

5

suggesting a collecting trip to Colorado. He also wrote to Hazel

Schmoll

6

, who owned a nature preserve near Rocky Mountain National Park, inquiring about accommodations. Schmoll, the former Colorado state botanist, usually advertised for guests to her ranch in the

Christian Science Monitor

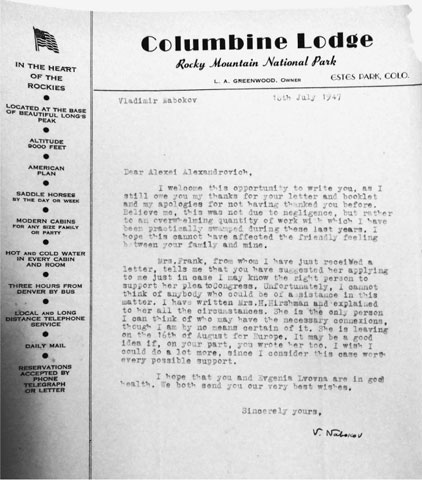

; Nabokov declined to stay with her when he learned that she favored guests who did not drink.

He did go to Colorado the following summer. The trip became possible with the receipt of an

advance of $2,000

7

for

Bend Sinister

, and in general things were looking up for him financially: his salary from Wellesley was now $3,250, and his MCZ stipend and yearly advance from

The New Yorker

contributed to a respectable total, enlarged by the occasional

book-talk fee

8

. The family went west by train. Dmitri was now thirteen and six feet tall; to go west for him meant to go to high mountains again, where he could hike and climb. Nabokov’s collecting needs dictated the itinerary. Tips from entomology friends, such as Comstock of the AMNH and Charles Remington, were useful, but by now Nabokov had examined many thousands of specimens, cataloging many of them

de novo

, and his own sense of where to look was astute. The names of North American sites of collection, some of them famous, some not, were sharply present in his mind. Chivington, Independence Pass, and La Plata Peak in Colorado; in Arizona, Ramsay Canyon and Ruby; West Yellowstone; the Tolland bogs; Polaris, Montana; Harlan, Saskatchewan. He

had been reading entomological

9

literature for forty years. His MCZ notecards display an astonishing appetite for detail, morphological detail above all—wing-scale counts, sex-organ descriptions, portraits of polytypes—and secondarily the details of discrete moments of capture. “

Taken by

Haberhauer

10

near Astrabad, Persia,” he wrote about one insect collected seventy-five years before, “probably in the Lendakur Mts … . where in summer 1869 he spent 2½ months, from the 24th of June, ‘in a village where shepherds lived only in summer,’

Hadschyabad

, 8000 ft.”

Another

notation preserved some suggestive phrasing: “

jam of logs

11

[in the Priest River, Idaho] stranded on its sandbars and a scurry of clouds mirrored in the dark water between its high banks.” He liked poetic touches—they were part of the specificity that he honored. About

Lycaena aster

Edwards, a copper butterfly, he recorded, “In the summer of 1834 it was nearly as abundant as

Coenonympha tullia

[of] Carbonear Island … where every step aroused numbers of these bright little creatures from the grass.”

A more typical, substantive notation, showing his precision and alertness to the naturalistic big picture:

*

N. Colo

12

., Spring Cn. [Canyon] W. of Fort Collins, alt. 52–5500 ft., arid grassy foothills, Upper Sonoran Zone with Transition elements, and 23 miles up Little S. Powder R[iver] Cn. from “The Forks” (alt. 6500 ft), Transition Zone, with Can[yon] Z[one] elements; Bellevue, Larimer Co[unty] alt. 5200 ft. Dry meadows and flats. Three Life Zones … noted within a horizontal distance of 6 mi.