Nabokov in America (21 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

In his scientific papers he sounded Nabokovian: artful, expressive, prickly-charming. He wrote,

On a hot August

13

day, from a bridge in Estes Park, Colo., my wife and I watched for almost a minute a striped Hawk Moth (

Celerio

) poised above the water, facing upstream against a swift current, in the act of drinking. The delicate wake produced by the immersion of the proboscis was a special feature of the performance.

In a paper published in

Psyche

:

When the whole [male organ of a Blue]

is forced open oysterwise

14

so that its symmetrically extended valves continue to point down … the most conspicuous thing … is the presence of a pair of formidable semi-translucent hooks … facing each other in the manner of the stolidly raised fists of two pugilists … with [a hood-shaped feature] lending a Ku-Klux Klan touch to the picture.

He was gracious but argumentative. Fools had made a mess of Lycaenid nomenclature, he said, identifying species falsely, and he campaigned against their influence the way he’d campaigned against “issue” novels and reading for “meaning”:

It may well be

15

… that a well-marked Washington form near

ssp. scudderi

is disguised as “

Plebeius Melissa

var

lotis

” in Leighton’s incredibly naïve paper … where utter confusion is achieved by references … to Holland’s hopelessly unreliable book. In this connection, it is worthwhile repeating that Holland … figured … the “type” of

Lycaena scudderi

Edwards [as] a male of

melissa samuelis

Nabokov … which is one of the reasons I do not attach any importance to Chernock’s vague statement … that … he

found “two males … that may be part of the series given to Edwards by Scudder.” The confusion … runs through the whole literature.

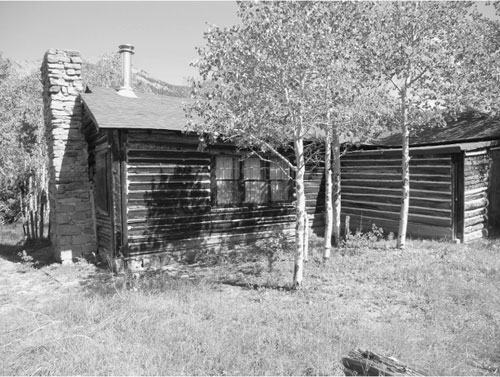

Longs Peak, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Earlier, in his first papers, he had been warmly charming. He wrote in the tones of the gentleman naturalist of the European nineteenth century, less concerned with scientific rigor than with style:

I had done no collecting

16

at all for more than ten years, and then quite suddenly a stroke of luck enabled me to visit … the Pyrénées Orientales and the Ariège. The night journey from Paris to Perpignan was marked by a pleasant though silly dream in which I was offered what looked uncommonly like a sardine, but was really a tropical moth.

America made him more scientist, less flaneur. It gave him intellectual tools—sex-organ dissection and reliance on the microscope; focus on the Blues—while putting at his disposal the marvelous MCZ. The distance traveled from dreams of sardines to the lab notations of the forties is large:

[

Icaricia

icarioides

, Boisduval’s Blue]

can be defined as a Polyommatus

17

with an Aricia-like organ. There is however one peculiar “American” character which it shares with

shasta neurona

: this is the remarkable glass like thinness … of the falx [part of the male organ] which is very wide … but tapers almost at once as it goes up producing an impression of atrophy … and recalling a piece of pointed candy that has been very thoroughly sucked.

By ’47 he had written astute, far-seeing papers, sent copies to close comrades, and become the

center of a coterie

18

. Instead of Hazel Schmoll’s ranch, with its prohibition on strong drink, he

boarded at Columbine Lodge

19

, a forty-year-old hotel-with-cabins mentioned in the 1947

Western Travel Guide

of the AAA. A number of entomologists from his circle came to see him

during his stay

20

there. Charles Remington drove him south to

Tolland Bog

21

, a brushy, moist bottomland along South Boulder Creek, at an elevation of nine thousand feet. “I was under the vague impression that he was a writer of novels,” Remington would recall forty-five years later; “we never talked about that side of his productivity.” Instead they chatted about “recent specimen collecting and

research” that each had done, reveling in their shared obsession. Nabokov was “quite equally passionate” about it—and the real pleasure of the day was the sport of it, the physical effort,

feet-on-the-boggy-ground

22

in the Rockies, in the summertime.

Columbine Lodge, four miles from 14,259-foot Longs Peak, offered rooms with bath or without and was deemed “Attractive” by the AAA. Nabokov wrote Wilson, “

We have a most comfortable

23

cabin all to ourselves.” The

lodge was within a half-mile

24

of the better-known Longs Peak Inn and a mile from the popular Hewes-Kirkwood Inn, a storied resort built by Charles Edwin Hewes, author of

Songs of the Rockies

and other works of poetry.

†

James Pickering, another local author, described the locality at the time of Nabokov’s visit:

It was

to the Tahosa Valley

25

that I came as a boy in 1946, following the footsteps of my father… . The “cabin,” as we called it, was a magical place … for a boy from suburban New York. There were two large bear rugs (whose heads and paws still had their teeth and claws) on the floor of the living room in front of the massive two-story moss rock fireplace; a dramatic view of the East Face of Longs Peak … and, in the corner, an old wind-up victrola with its collection of raspy dance records… . There was no electricity or in-door plumbing, and food was kept in a “cave” just off the back porch, which “Uncle Fred and Aunt Jessie” told us had once been scavenged by a bear, later captured and sent “over the mountain.” There were kerosene lamps … and a whole stack of paperback novels by Zane Grey and Luke Short.

To Pickering, “this was, surely, the West!” Columbine Lodge looked east to the Twin Sisters, eleven-thousand-foot pyramidal peaks of the Colorado Front Range, and west to Longs and other mountains of the Continental Divide. The valley between these two ranges was high meadow, crisscrossed by streams fed by springs and snowmelt,

with beaver dams

26

. Nabokov reported to Wilson that the “flora is simply magnificent,” and his family’s long stay—late June to early September—allowed them to witness successive wildflower outbreaks. On rising ground, the

kinnikinnick gave way

27

to lodgepole pine mixed with ponderosa and juniper, with many aspen stands.

Véra enjoyed

28

the summer, although annoyed that nowhere in Estes Park, the nearest sizable town, could she find a copy of the

Saturday

Review of Literature

, which she and her husband liked to read. Dmitri climbed Longs Peak. Late in July, a collector from Caldwell, Kansas,

Don Stallings

29

, made pilgrimage to meet Nabokov in person—they had been corresponding since ’43, when a friend at the MCZ had sent Stallings a paper that Nabokov had written (probably “

Some new

30

or little known Nearctic

Neonympha

,” which recorded his Grand Canyon captures). Stallings, a lawyer, asked Nabokov to help him determine some specimens, offering to pay for the service. Nabokov replied, “I shall certainly be very glad to determine your specimens.

There will not be any fee

31

.”

In a thank-you letter, Stallings wrote, “I was pleased to note that the wife and I had as a general rule correctly identified these specimens… . In the future in your research if we have any specimens that you wish to borrow, please feel free to do so.” He added, “Of course I realize that our collection is not as large as some, still it does represent some 10,000 North American Butterflies covering a little over 1100 species—plus

a flock of unnamed races

32

which … we do not have sufficient material at the present time [to determine].”

This was an enormous personal collection. Within a few years, Stallings,

tutored by Nabokov

33

, went into business as “Stallings & Turner, Lepidopterists,” furnishing materials to collectors and museums. The correspondence from the beginning had a comradely tone, with tongue-in-cheek sallies. Stallings, from his home on the Oklahoma state line, had ranged throughout the Southwest and into Mexico, and Nabokov relied on him for information on sites; when thinking of going to Alta in ’43, he first

ran the idea by

34

Stallings.

Vladimir’s reliance on the microscope had a galvanizing effect. In a paper he co-wrote for the

Canadian Entomologist

, Stallings said, with the certitude of a new convert,

This giant race

35

of the species

freija

Thun. was collected along the Alaska Military Highway in British Columbia. In size and wing shape this would appear to be a race of

frigga

Thun. rather than of

freija

, and we have no doubt but that those who depend on external characters only will insist that we are in error; nevertheless gentalic study leaves no doubt as to its true relationship with

freija

.

Stallings prepared for his Alaska trip by studying specimens Nabokov had loaned him from the MCZ. “Yes we’d like to borrow the Alaska Highway specimens,” he wrote in April ’45, after first declaring,

You will find

36

… that in some ways I’m rather lazy—and if another fellow has done something I usually ask him for his results before I dig in myself—hence I’d like to see a rough sketch of yours of the genitalia of

pardalis

indicating where it differs from

icarioides

and you didn’t send me any sketches of the innards of the Melissa-scudderi-anna group.

He confessed that “

my ideas run along

37

similar to yours—but I always find you about ten good full strides ahead of me.” Then, in ’46, Stallings wrote, “

Also received

38

your latest paper which is more nearly a book. Thanks. I like your genitalic work. Have hopes of … doing some of that myself.”

Stallings asked Nabokov to

teach him the names

39

of genital parts. Soon he was replicating, as far as he could, Nabokov at work at his bench in the MCZ:

Did some dissecting

40

the other evening. A couple of icarioides and one specimen of what I thought was a pardalis, but didn’t see any … differences, though I haven’t made sketches yet of the valves and falax and uncas lobe. I can’t get a scope—so am using a borrowed one with 90 power … hence I can’t do any 300 times looking.

With Stallings, Nabokov engaged in advanced shoptalk. From him he heard of, or heard more about, the concerns of an American man of that time; Stallings wrote that he dreamed of going collecting the following summer “if

Uncle Sam

41

doesn’t want to send me traveling first,” and he also wrote, “Had a letter from my brother-in-law Dr. Turner, he parachuted into France on

D-Day

42

and is still going strong. As soon as the war is over … we have hopes [of collecting in southern Alaska].”

Near the end of

Lolita

, whose composition Nabokov

dated from this time

43

, the heroine, married at seventeen, contacts Humbert Humbert three years after having escaped his captivity.

Humbert drives immediately

44

to the city she writes from, a town he calls Coalmont, “some eight hundred miles from New York City” (“not ‘Va.,’ not ‘Pa.,’ not ‘Tenn.’—and not Coalmont, anyway—I have camouflaged everything,” he says). Lolita is pregnant. She asks for a few hundred dollars so that she and her husband, an ex-GI, can move to Alaska to begin a new life. Humbert intends to kill the husband but relents upon seeing how young he is. He implores Lolita to return to him; she

refuses. So absolute is the sentence of catastrophe upon everyone in this supposedly comic novel that Lolita, although miraculously intact after her cruel youth, wonderfully seasoned, in fact, and movingly decent in her young womanhood, will soon die in childbirth, and the faint wash of hope in the dark sky of the story comes to bleak nothing.