My Sergei (18 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

For me, it was all much more stressful than when we’d skated as amateurs. Meanwhile, everyone else was so friendly and relaxed,

always smiling. On the night of the competition, I fell on one of the throws, and in general we didn’t skate very well. The

Canadian pairs team of Paul Martini and Barbara Underhill beat us. They were fabulous. Then in our second professional competition,

in Barcelona, we finished second to Martini and Underhill again. But this time, at least, we skated better. And we won twenty

thousand dollars each time out. I was a little upset at being second, but Tatiana told me, “Don’t worry. Barbara and Paul

know how to present themselves so well, and you will learn.” Technical elements are not nearly as important in professional

competitions as presentation.

New Year’s 1991, we celebrated in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, where they staged an annual ice show. We’d now been in love for

two years. The next morning Sergei said to me, “I want to buy you something, Katoosha.”

He almost never bought me presents without asking me to help him pick them out, no matter how many times I told him I liked

to be surprised. Just give me something, Seriozha. Anything is fine, I’d tell him. But his eyes would become like a little

puppy’s, and he’d say, “But I want to give you something you want. Please help me. We’ll find something together.”

So this time we went to an antique jewelry store in Garmisch, and he asked the lady if she had any rings. They didn’t have

a very big selection, but the lady showed us one we liked, an emerald, with small diamonds on the setting. Sergei bought me

this one. The lady was so pleased that she gave me a cross made of rubies. Maybe they weren’t real, but they looked like rubies,

and I loved this cross. And I especially loved my emerald ring, which I still cannot ever take off.

In Russia we don’t have engagement rings. Just wedding rings, which are simple bands of gold. So this emerald ring didn’t

really mean anything. It just meant Sergei had given me a gift. But later everyone was asking me if it was an engagement ring.

And I told them it was, because the wedding was so close.

My mom was overseeing the renovation of Sergei’s apartment, which was going to be ready in April. Then, naturally, he would

expect us to move in. When I realized that Sergei wasn’t going to do anything about getting a wedding license, I took it upon

myself to look up in the Russian yellow pages where we could apply for one. Sergei never planned anything. Things just happened

naturally with us, but in this instance I helped them along a little bit. In January we went together to this application

office, and the lady asked us if we were in a rush or if it would be okay to wait for three months to get the license. We

said three months was fine. She looked at her calendar, because the wedding dates were filling up fast, and we ended up choosing

April 20.

You know, we should have been so happy that year, because it was the year we were getting married. But in truth that was the

only thing we had to be happy about. We just didn’t seem to have luck that year. We’d changed coaches, had lost Marina as

our choreographer, and were traveling by ourselves. It was all too much for us. Plus, Sergei’s shoulder was getting worse

and worse. He couldn’t do any lifts at all, and couldn’t even sleep on his right side. I thought that his skating career might

be over.

Paul Theofanous finally got us an appointment to see Dr. Jeff Abrams in Princeton, New Jersey. They did an MRI—magnetic

resonance imaging—which was very scary for Sergei, since we had never seen this machine before. He had to lie in this tiny,

vibrating, moaning capsule without moving for twenty minutes, just the top of his head sticking out. When the doctor looked

at the image, he recommended that he operate arthroscopically on the shoulder in the next couple of days, to clean out the

dead tissue and put a miniature camera in there to see just what was wrong.

The operation was set for February 14, Valentine’s Day. We were staying in Paul’s apartment in New York, and every day I went

for long walks through the city and runs through Central Park. I fell in love with New York during that stay. In other places,

life goes on very slowly. But in New York, everyone is walking, everyone is busy, everyone knows exactly where they’re going.

The people are so solid, so intensely into themselves. They barely acknowledge each other. Always you see them thinking to

themselves, talking to themselves. The huge buildings seem to give birth to this great well of adrenaline and energy and power.

Life’s routine is so much faster and more exciting. Moscow is getting more like that now, but when I was growing up there,

people didn’t rush anywhere, and everything was much, much calmer. People knew their jobs would still be there when they arrived;

their salary would still be paid. No need to rush to the grocery store because you couldn’t get anything there anyway.

I even liked the homeless people in New York. At least I liked the homeless man who lived outside Paul’s apartment. Paul always

said hi to this man, and every morning he gave him a few cigarettes. So Sergei and I became friendly with him, too. We’d talk

and smile. Sergei was very shy with high-level persons, but with common people he was quite at ease and open. This homeless

man was friendly, and he never asked us for things. Quite the opposite, sometimes he would tell us things he thought we should

know. Weird things, maybe, but interesting, too.

On the day Sergei was scheduled for surgery, Paul drove him to Princeton. Sergei didn’t really want me to have to wait around

the hospital all day. He didn’t like me to see him when he was in pain. So I stayed behind to prepare a nice dinner for when

they returned. First I went to buy flowers to give to Sergei for Valentine’s Day, and that was a crazy experience. The lines

in the New York flower stores were so long I couldn’t get in, and some of the florists were completely sold out. I was looking

for tulips, which were Sergei’s favorite. Finally I found some in about the tenth store that I went to, and I also bought

candy, fresh fruit, and the ingredients for our meal. I decorated the apartment so everything looked romantic.

They came back around dinnertime. Sergei’s arm was in a sling, but otherwise he looked fine. He told me everything had gone

well. I gave him the flowers, and he said to me, “Katuuh, do you want to see a movie? We brought you one.”

“Okay. If you like.”

“It’s scary though.”

“That’s okay. I like scary.”

Paul put the tape in the VCR. It was a movie of the surgery they had performed on Sergei. The camera was inside his body.

“You see, this is the bad part,” Sergei said, pointing to some dead tissue inside his shoulder. “Now the doctor is cleaning

it out. Look.”

It was quite disgusting. So much for the romance of my first Valentine’s Day in the United States.

The doctor had told Sergei that he had to come back for another surgery, too. He’d discovered the torn rotator cuff, which

was a very bad injury. They made the appointment for mid-April, just a few days before our wedding.

Sergei flew back by himself for the second operation. He was only going to be gone a few days, but he had never traveled to

America without me—we had traveled so few places alone—and I was very, very worried.

I was busy preparing for the wedding, which was actually going to take place on two different days. The official state-approved

wedding was on April 20, when we were scheduled to pick up our license. Then the church wedding, performed by Father Nikolai,

and the banquet with all our friends was going to be eight days later, on April 28. Unfortunately, Marina was not going to

be able to be there. I called her to tell her the date, but she said she had already signed a contract to coach in Ottawa

and was leaving for Canada April 22. She couldn’t change her plans, but told me that if I ever needed help, to contact her.

And she asked that we not forget her.

Sergei didn’t call me after the operation, because he was flying back the next day. When I went to meet his plane, I brought

one red rose. I had never gone to meet him at the airport before, and I never would again. This was the only time. He came

through the customs line, and his face was so sad. Paul Theofanous had given him two goose down pillows for a wedding present,

and Sergei had those pillows under his good arm. His other arm was in a sling, and he had his one small bag slung over his

shoulder. He’d been taking the pain pills the doctor had given him, so he looked like he was drunk.

I couldn’t help smiling, he looked so funny. I know that wasn’t nice, but I was so happy to have him safely home, I couldn’t

control my smile.

The next morning we had the appointment to get our marriage certificate, and afterward there would be a small party, just

for our families. I didn’t wear my wedding dress on this day, but once we had the certificate, it meant that we were legally

married. Sergei came to pick me up carrying a huge bouquet of roses, but he had forgotten his passport, which he needed to

get the license. So he went back to his home to get it, while I went ahead to explain to the officials he would be late. I

was worried that if we missed this appointment, it might be another three months before we could get another one.

The ceremony, once Sergei arrived with his passport, was very quick. Yegor was his best man, and my maid of honor was a girl

I’d met at Yegor’s, also named Katia. I really didn’t know her very well, but I couldn’t choose my sister, Maria, to be my

maid of honor, and I really didn’t have any other close girlfriends in my life. Afterward, we celebrated with a small party

in my parents’ apartment, and the only sad thing about this day was that my Babushka, who was so important to my childhood,

was in the hospital, very sick with cancer, and wasn’t there.

That was the first night we spent in Sergei’s new apartment. He didn’t carry me across the threshold—this isn’t a custom

in Russia—and even if he’d wanted to, he wouldn’t have been able to because of his shoulder. He could barely sign for the

marriage certificate. The apartment, which I hadn’t seen since my mother had renovated it, was beautiful. She had removed

the doors between the living room and kitchen, so that now there was a little arch. She’d decorated it with a little table,

two armchairs, and a convertible bed that she’d left folded out for us. She’d also left a bottle of champagne on ice, and

fresh flowers. This apartment was the best gift she could have offered us: a new world for Seriozha and me.

I felt different. Not more nervous, but I’d been waiting to marry Sergei for such a long time. We had shared our bed in many

places before, but now that we were married I was thinking I had to do something different. Something special. I was expecting

something like Paris again, I guess. But it wasn’t this way. Except that now we had a home in which I could take care of my

Seriozha, stay with him and cook his favorite meals.

The church wedding was eight days later. Many of our friends were coming into Moscow from ice shows all over the world. Marina

Klimova and Sergei Ponomarenko, and Maia Usova and Alexander Zhulin came to the restaurant directly from the airport. The

speed skater Igor Zhelezovsky was there—Sergei had been his best man. Leonovich. Tatiana Tarasova. Terry Foley had come

in from California, and he videotaped the ceremony for us.

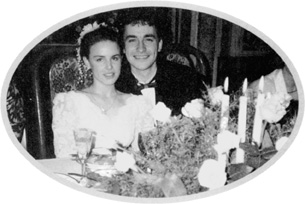

The wedding was at 4:00

P.M.

at the small church in which I’d been christened. I wore a silk, off-white dress that I’d bought in Toronto, and I was wearing

flowers in my hair. It rained all morning and most of the day, which was considered good luck. It doesn’t seem like it now.

But I was happy that it rained. After saying our vows, we drank champagne in the church, and Father Nikolai sang to our happiness.

Then we drove to the restaurant in a white Mercedes that had been loaned to us by the director of Tatiana’s show.

At the wedding banquet, everyone kept toasting us, saying “Gorka! Gorka!” which is a signal for the bride and groom to kiss.

As long as the guests are still chanting Gorka! you have to keep kissing. It means “bitter,” so you have to kiss sweet. The

whole wedding people kept saying “Gorka!” A hundred times at least. The only time I remember seeing Sergei that night was

when we kissed.

To tell you the truth, I didn’t have the greatest time at my wedding. It wasn’t the best day for Sergei, either, though Sergei

always liked seeing his old friends. He didn’t like being the center of attention, and he didn’t like it when all the women

were asking him to dance. I think people sensed he was a little annoyed, because they didn’t do the tradition we have in Russia

of stealing the bride and hiding her during the banquet. Then the husband has to pay to get her back.

That night Sergei and I danced our first real waltz. He said, “I don’t know how to,” and I told him, “I don’t either. Let’s

just try something.”

We had skated to two waltzes when we were competing, including the 1989 program in which I pretended to be a young lady dancing

the waltz at her first fancy ball; but this was very, very different. We were not good dancers on the floor, I can definitely

say this. I was so happy when the banquet was over and we went back to my mother’s for a more informal after-party. All the

skaters came back, and the apartment was filled with people. Parking was a big problem. Every time someone wanted to leave,

he had to come back into the building, take the elevator back up eleven floors, and ask about eight people to move their cars.