My Sergei (16 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

Both the men were very drunk, but one was drunker than the other, and this man grabbed me from behind. I was so scared that

I tried to scream but couldn’t. This was the first time I ever learned about being so frightened that you cannot make a sound.

I tried to hit him with my elbow, and with my foot tried to kick against the wall to Sergei’s room. But I couldn’t do it.

Thank God the other man came back and told his friend to let me go. Then he led him away.

Surprisingly, they came back a short time later. They knocked on my door, and I again opened it for them. I must have been

very sleepyheaded. When I realized my mistake, I tried to slam it shut again, but they didn’t let me. Again, thank God there

were two of them, because the one who was not so drunk said, “Come on, let’s go. People will hear us.” And he pulled the drunk

one away from the door. They came back a third time, too, but this time I left the door locked. I was so embarrassed about

the whole incident that I didn’t tell anyone this story the next day, and only mentioned it to Sergei years later.

That fall Sergei’s dog, Moshka, died. We had been at an exhibition in Germany, and Sergei’s mother, Anna, was taking care

of the dog. It stopped eating one day, and she didn’t do anything about it at first. When Sergei came home, he took Moshka

to the vet right away. It had been four days since she had eaten. Sergei had not given Moshka her puppy shots, and she was

suffering from distemper. The vet gave her these shots, but by then it was too late. Sergei took Moshka home, and that night

the puppy pushed open his bedroom door, which she had never done before, and Sergei lifted her into his bed. Two hours later

she died.

Sergei called me in the morning and told me. It was very, very sad for him. He buried her near his home, in the forest, and

didn’t skate that day. He later said to me, “Why do things happen to the ones I love?” And that was the first time he told

me that his best friend had died a few years earlier in a car crash. It was the younger brother of Viacheslav Fetisov, the

famous Red Army hockey player, who later came to America and played in the National Hockey League. A short while later I gave

Sergei a porcelain figure of a white bullterrier with a black right eye, just like Moshka, which he always kept, and I have

still.

• • •

Sergei’s shoulder started bothering him that year. Leonovich had taught us a new lift that we called a loop lift, in which

my feet were positioned as if I were doing a loop jump, my hand was behind my back, and Sergei took this hand and lifted me

up with one arm as I split my legs. I never saw anyone else doing this lift, but it was the move that hurt Sergei’s shoulder

—although we didn’t realize it for a long time. It bothered him enough that we had to drop out of the Nationals, missing

them for the second year in a row.

He didn’t complain, but I knew he was in a lot of pain. The doctors at the Central Army Hospital said there was nothing they

could do except give him shots to ease his discomfort. They thought there was some problem with his muscles, but they really

had no idea how to cure it, and it was a year later that a doctor in the United States figured out that he had torn his rotator

cuff.

For New Year’s 1990, we again returned to celebrate with Yegor. So much had happened in the last twelve months, so much within

me had changed, I could hardly believe it was just a year ago that Sergei had kissed me for the first time. Now, of course,

as I write this, I’d give anything to go back and relive 1989. Every moment of it, good and bad, starting with the trip to

Sasha Fadeev’s sauna, then to Birmingham, to Navagorsk, to Paris, to the dacha in Ligooshina, even to Terskul, with the drunks

on the balcony. I’d go back there in a heartbeat, and remain.

But I held no such nostalgic notions at the time. It seemed as if the happiest years with Sergei were just beginning, that

the best times were in the future, not the past. Nineteen ninety was just one more New Year’s Eve at Yegor’s. I had no desire

to drag Sergei back to Fadeev’s sauna, to relive our special kiss. I could kiss him anywhere I liked now—anytime, with anyone

watching. We danced a lot. We drank champagne. We watched the fireworks. In Russia, each New Year has a special color, and

I remember that in 1990 the color was white. Sergei wore a white sweater I had knitted him, and as always, he looked very,

very handsome. My parents, again, were there; my sister, Maria; Sasha; and lots of Yegor’s friends. People from his village

used to drop by his home to celebrate every New Year, because everyone knew Yegor, everyone liked him, and this tradition

brought all the people luck.

The European Championships that year were in Leningrad, and we weren’t in very good shape. Sergei’s shoulder was only part

of the problem. I was still having difficulty with my jumps, because of my body change. In the short program at Leningrad

we were atrocious. I missed the double axel and slipped doing the death spiral. Also one of our spins was not in sync. The

next morning we heard on television that the Moscow pairs team of Gordeeva and Grinkov was very bad and probably could not

win the gold medal. It motivated us, and the day of the free program Marina told me, “Ekaterina Gordeeva, you’re the Olympic

champion, remember?”

It helped me. Those were the only words I remember a coach saying to me before I skated that actually helped me. I still think

of those words sometimes before I take the ice. In the long program, we skated

Romeo and Juliet

very cleanly, and everyone loved it, and we came back from third place to win. This program, which Marina had created to

reflect the feelings we were having for each other off the ice, was a big plus for us all year. I felt like I understood the

reason behind every movement I made. But even though Sergei skated this program so tenderly, and looked at me always so lovingly,

we were all business on the ice. We never complimented each other after we skated. He never whispered in my ear, “I love you.”

That was for later, when we were off the ice. Though to be honest, Sergei was never much of one for compliments or flattery.

He never said I looked beautiful, or fresh, if I tried to look especially nice for him. The most he ever said was “Wow,” although

he said other things with his eyes.

We didn’t skate our best at the 1990 World Championships, either, which were held in Halifax. Again, we won, but I two-footed

my triple toe jump and fell on the double axel. Afterward Sergei said to Marina, “What if I missed a jump? Can you believe

how bad I would look? Katia’s little, she’s tiny, she’s a girl. But if I missed, what do you think would happen?” He dreaded

this thought. He was all the time worried about me, and I never, ever worried about him.

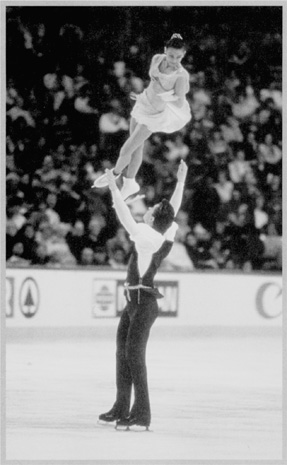

Gerard Vandystadt/Allsport

1990 World Championships

• • •

We again went on the Tom Collins tour that spring. Financially, the way it worked was that Tom would give all the skaters

money for the first third of the tour, then the next third, then the last third. The skaters from the Soviet Union, however,

were not allowed to open their envelopes until the head of the Soviet skating federation, Alexander Gorshkov, came to pick

them up. Then he’d give us some money back. I never knew if the money we were getting back was one-quarter of what Tom paid

us or one-half. We were always upset it wasn’t more, because we saw that skaters from the other countries got to keep all

the money that they were paid. Eventually we started to complain as a group, led by our coaches, and Gorshkov began giving

us a little bit more. We still spent everything we earned.

The Russians on these tours always liked to have room parties together. The boys would buy the liquor, and the girls would

buy the food—salami, peanuts, gherkin pickles—which we washed down with a shot of vodka. We didn’t have so much money

that we could order room service.

This particular time I roomed with Galina Zmievskaya, who was Viktor Petrenko’s coach. She always had smoked meat, salami,

sausages, and a huge chunk of chocolate that she carried along for meals. We saved money this way. It’s why I always brought

along a hot water kettle for making coffee and tea. Galina made Viktor, Sergei, and me feel like she was the mom taking care

of us. In the morning she’d wake up and say to me, “Let’s call our boys and ask them for breakfast.” Then she’d call Viktor

and Sergei, who were also rooming together, and would break out her food.

Viktor was always very quiet around me, but friendly, and absolutely dependable as a friend. I respect him even more as a

person than I do as a skater. Any favor you asked of him, he’d say it was no problem. He told Sergei that if he ever wanted

to have the room to himself, he’d be happy to move somewhere else for the night. But we never asked him to do this.

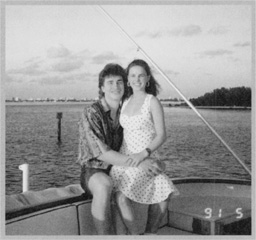

Time off during our 1990 Tom Collins tour.

Viktor worked very hard with Galina, and I was amazed how much time they spent together, both on and off the ice. I didn’t

realize it then, but Viktor was already engaged to Galina’s daughter, Nina. He and Galina would go to restaurants together,

go walking together, everything. He never went out at night with the other men. And Galina wouldn’t let him play basketball

or soccer, which all the other skaters did, for fear he would hurt himself. I thought it was all too much. But I never heard

Viktor complain about it.

When the tour got to Washington, D.C., we were staying at the Four Seasons Hotel when Viktor called me very late one night.

He asked me if I could come to his room right away. He had something important to tell me. When I got there, Viktor said that

Sergei had just gotten a call from Leonovich. Sergei’s father had died of a heart attack. Sergei had put his clothes on and

gone out, Viktor didn’t know where. He thought we should go look for him.

We started checking the bars in the area, but we couldn’t find him. Finally we returned to the hotel and found Sergei sitting

at the bar. He couldn’t talk about his father then, and I didn’t know what to say. I just hugged him. I just tried to hold

him all the time. It was the first time I’d ever had a close friend have someone in his family die, and I felt so terrible

because I didn’t know what to talk to him about.

Sergei was crying, and he told me, “I didn’t spend enough time with my father.”

I, too, wished I had spent more time with him. I still feel this way, because I only met him two times, and his father was

the one whom Sergei resembled, on the inside and the outside. He was so big and so solid.

The next morning Sergei flew back to Moscow on the first flight he could get. He didn’t want me to come, but I drove him to

the airport. I later learned that my mother was a big help finding a cemetery plot for Sergei’s father. These plots were in

very short supply in Moscow, but my mother offered Anna a place in the plot of her own family.

Sergei came back to the tour shortly after the funeral. He was exhausted and looked as if he had lost weight. I bought him

flowers and champagne. He brought me a bottle of cognac. I was so happy to see him, but he was too filled with grief to be

happy.

He said to me, “Every year, it’s something. First my best friend. Then Moshka. Then my father.” He was also very concerned

about his mother, Anna, because she was inconsolable when he’d been back in Moscow. His father, who’d had three heart attacks

earlier in his life, had collapsed in Anna’s arms. She had held him as he took his last breath. It was just the two of them

at their dacha, which he had built with his own hands, and there was no phone and no one nearby to come to help her. So it

was very hard on Sergei’s mom.

I asked Sergei to tell me stories about his father. He said he was just a quiet man who liked to be alone, and who was a high-ranking

officer in the police. It wasn’t much to be left with. Sergei had never spent very much time with his father, since he had

never been involved in Sergei’s skating. It was his mother who oversaw all that. Sergei, I knew, would be much more involved

in the lives of his own children. Some men are natural fathers, even before they are fathers, and Sergei was this kind of

man.