My Sergei (17 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

I

n May, just prior to my nineteenth birthday, I was

baptized. My mom had become good friends with a neighbor who was very religious, and they decided that since the churches

were reopening in the Soviet Union, it was time I should be christened in the Russian Orthodox faith. When my mother was four

years old, she told me, her grandmother had secretly had her baptized. She further explained that if I wasn’t christened,

it would be impossible for me to be married in a church. “Katia,” she asked, “don’t you want to be married in church?”

I told her I did, although no one had yet spoken to me of marriage. I’d started to like churches since Sergei had taken me

by the hand into the stunning cathedrals of Milan and Paris. I loved the way the music sounded as it echoed off the stone

walls. I thought a church would be a beautiful place in which to be married.

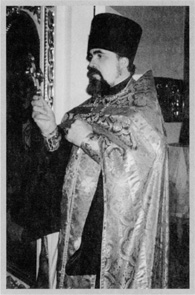

This friend of my mother’s said she knew a very good priest, and she introduced me to this priest when he was visiting her

family one day. His name was Father Nikolai, and I immediately liked this man. He had a very kind face. He was forty-five

or fifty years old, and had long, straight black hair, which was always brushed carefully. His beard was also long and had

streaks of gray in it. His eyes were very gentle, and he spoke in a soft and soothing voice.

I didn’t know anything about religion. I didn’t even know how to cross myself, but Father Nikolai never made me feel shy about

it. He just told me he would give me some prayers to learn, or if I didn’t have time to learn them by heart, I could read

them. He didn’t preach to me about doing this and this and this. He simply told me I could always come talk to him if I felt

the need to. He made it sound as if he would be the guardian of my spirit, and he has turned out to be just that.

Father Nikolai’s church was called the Church of Vladimir the Conqueror. Churches in Russia are always named after the oldest

icon in the church’s collection, and this icon of Vladimir the Conqueror shows him riding a horse and carrying a spear. It

is a warlike pose, and he does not appear to be a very holy figure. But he is probably poised to drive off the barbarian infidels

and save many defenseless Russian churches, which is why, many years ago, they created this icon of him. Father Nikolai asked

if I wished to be christened in the Church of Vladimir the Conqueror by myself or with other people, and I said I preferred

to do it alone.

Father Nikolai

They had just finished adding a small church to the courtyard beside the big church, and this was where the service took place.

Everything was new and beautiful, and I was the first person christened in this little chapel. In Russia, you are baptized

while wearing only a nightshirt, so Father Nikolai told me to bring a white nightshirt and my own cross. He would bless my

cross by immersing it in the holy water. Then he would splash this water all over me. The water was supposed to be cold, but

the lady who was helping Father Nikolai took pity on me and brought in warm water so I wouldn’t freeze. It was very private:

just Father Nikolai, this lady, and me. I had asked my parents and Sergei not to come. It seemed to me that such a moment

should be a personal affair.

Afterward, I didn’t feel particularly different, but I did feel the baptism was something special and a little exciting. Something

had changed, even if I couldn’t explain what.

• • •

Almost every other weekend in the summer, Sergei and I went to visit Yegor at his house on the Volga River. It was beautiful

there. Sergei thought this was the best vacation you could have: fishing, walking in the forest, being outside, making dinner

from the fish that you caught. I agreed with him.

Then it was time for the usual visits to training camps: Sukhumi and Navagorsk in preparation for the Goodwill Games that

were being held in Seattle. Sergei’s shoulder was still bothering him, and while we skated well in practice, during the actual

Goodwill competition we were terrible. I fell doing a double axel and again two-footed my triple toe. It was quite upsetting,

and I began talking to Sergei about the possibility of changing coaches. We just hadn’t skated that well the year before,

despite winning, and I wanted someone who would push us a little harder. Since I was the one making the mistakes on the ice,

I was the one who wanted the change. But Sergei was starting to agree with me.

The Goodwill Games was also the place where we met Jay Ogden from the International Management Group (IMG) for the first time.

Paul Theofanous, who spoke Russian and also worked for IMG, introduced us. Paul was a Greek from New Jersey, but his Russian

was very good, and Sergei and I liked him.

He and Jay met with us for half an hour, explaining that IMG managed the careers of professional athletes. They owned and

produced the North American show Stars on Ice, and told us they could give us a contract if we agreed to turn professional.

They told us we could definitely earn more than a hundred thousand dollars a year, maybe much more, if we signed to skate

in the show the next season, and if we also competed in some professional competitions. But we didn’t take them very seriously.

It seemed more like they were trying to own us than help us. So we didn’t sigh anything then.

Besides, Sergei and I still wanted to skate in the World Championships, and maybe another Olympics, and if we turned pro we’d

lose our ISU eligibility. The ISU allowed skaters to be paid a small salary during tours that they sanctioned, such as the

Tom Collins tour, but it was a very specific amount, something like five hundred Swiss francs a month. It varied year to year.

As a professional, you could earn fifty times that amount, but those additional earnings came with a price. The biggest competitions

in skating—the World Championships, the Europeans, and the Olympics—were only open to amateurs.

We had a couple of exhibitions in Sun Valley after the Goodwill Games, then I went to visit my friend Terry Foley in California.

He had invited my sister, Maria, and mother to stay with him, and it was the first time they’d ever been to the United States.

I felt I should go, too. Sergei wasn’t very happy about it, though. He didn’t know what to make of Terry. He was a little

suspicious of his motives, even though Terry’s oldest daughter was older than me. So Sergei went back to Moscow on his own,

and I ended up being a rude houseguest who was always in a terrible mood, because I thought I should be back in Moscow with

Sergei.

That entire fall, and most of the winter and the following spring, was one of the most stressful periods of our lives. There

was still the matter of changing coaches to deal with, and when I got back to Moscow. Sergei and I talked to the skating federation

about this idea. Did they have any suggestions? Maybe Tatiana Tarasova, someone said. She had coached the famous pairs team

of Irina Rodnina and Alexander Zaitsev, who’d won two Olympic gold medals and six World Championships, before she coached

ice dancers Bestemianova and Bukin.

My father, in fact, was working for Tatiana Tarasova. She ran the Russian All-Stars skating tour that gave exhibitions throughout

the world, and my father was helping with the costumes. He started lobbying Sergei and me about joining the All-Stars and

having Tarasova coach us. Of course we wanted Marina to come with us, too. So when we agreed to have an interview with Tarasova,

Sergei called Marina to ask her to come along. But Marina wouldn’t do it. She told him she couldn’t work with Tarasova. They

were very different people. Both were choreographers, but they each had their own vision about what skating should be. This

meant we’d have to leave Marina, as well as Leonovich, if we went with Tarasova, which we eventually did.

Then Paul Theofanous came to Moscow to visit us, and it was during this trip that we agreed to sign a contract with IMG. That,

in itself, didn’t mean we had decided to turn professional. There were no numbers on this contract. IMG wasn’t paying us anything,

and we weren’t agreeing to skate in Stars on Ice. But the contract said IMG would represent us for the next two years and

could use our name to promote any events we were skating in.

Sergei and I made this decision together without telling anyone else. We started to work with Tatiana on our new programs

for the 1991 season, but Sergei’s shoulder was giving him a lot of pain, and all we could practice were spirals, steps, and

spins. No throws. No lifts. We didn’t feel we were growing as skaters. Sergei, especially, felt this. We were stale, unmotivated.

He said if we stayed amateur two more years, he wouldn’t want to skate at all afterward. We’d totally burn out. He said to

me, “Let’s turn pro before we get so sick of the ice we can’t look at it.”

We decided to talk to Tatiana about it. She’s a big woman, full of energy and with an endless stream of ideas. She is also

a chain-smoker with a thermos of pills in her bag for every conceivable ailment. But she was just the person we needed at

that point in our careers, always smiling and enthusiastic, very concerned about our health. We liked working with her.

Tatiana didn’t try to talk us into turning pro, or out of turning pro. She did say, however, that if we decided to skate professionally,

she would call Dick Button in New York and tell him that we’d like to compete in the World Professional Championships in Landover,

Maryland, in December. You could tell she thought it was a wonderful idea. She also said that if we joined her Russian All-Stars,

whose schedule conflicted with Stars on Ice, she would pay us a salary of four thousand dollars a week, every week, even when

we were training. That turned out to be a wildly inflated number, but Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean had just left the

All-Stars, and Tatiana was desperate to have some big-name skaters join her. That’s when we told her we had already signed

with IMG, which surprised her.

Sergei and I thought about it for a day, then decided to give up amateur skating. Tatiana said, “Great! I’ll call Dick Button!

We must start work today on your program.” Sergei and I never regretted our decision for a minute.

My father, however, was so disappointed. Here he had finally gotten us to go to a coach he approved of, and we were turning

professional. No 1992 Olympics. No Europeans. No Soviet national competitions. My father was like, “Oh my God, what have I

done!” He blamed it on Tatiana, mistakingly believing it was all her idea.

Tatiana had us working on new moves every day, and very quickly we had three programs to use in Landover in December. Professional

skating is quite different from amateur skating—less technical, more theatrical—and I think she is a better coach for

professionals than for amateurs. She likes creating dramatic programs rather than drilling her skaters repeatedly on double

axels and lifts and other required elements. I liked working with her. She had a real talent for talking to people, and was

great with Sergei. She really made him work. He might say, “That’s enough for today, I’m too tired.” And Tatiana would respond

sympathetically: “It’s crazy that we’ve been on the ice for so long, you’re absolutely right. You must be dead on your feet.

But before we go in, why don’t you try it this way one time so I can see it?” She kept him interested in what she was doing.

That was the autumn, also, that Sergei finally got the title to his apartment. It was on the fifteenth floor of a building,

and I remember the first time he took me up to see it. The people who had just moved out had destroyed it, so it was a very

dirty, very dark, very scary studio. It did have a nice balcony, but everything else was ugly and would have to be fixed.

It was on this first visit to his apartment that Sergei proposed to me.

It wasn’t the way Americans propose to a woman. He didn’t invite me to dinner. He didn’t give me a ring. He didn’t get on

his knees and ask me to marry him. Sergei just said, “I would love for you to live with me in this apartment.”

He was quite sincere, and to me it was very romantic. Of course we would have to renovate everything in this place before

it would be fit to live in. But I could picture how it might one day look, and that Sergei would want me to live with him

made me unspeakably happy.

F

or us, there was a huge difference between competing as

amateurs and competing as pros. First of all, in the professional ranks, there’s no organizational support. We were used

to having teammates, roommates, and a team leader who told us, Here’s when and where you eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Here’s your practice schedule. Here’s the bus schedule. Here’s your bedtime. Everything.

All of a sudden, Sergei and I had to figure everything out for ourselves. We were late for practices, we missed buses, the

ice we practiced on wasn’t freshly made. All of it was new. Peter and Kitty Carruthers, the American pairs skaters who’d won

a silver medal in the 1984 Olympics, hadn’t decided what program they were going to skate until the night before the competition.

Then when they did skate, it looked to me almost as if they were making it up as they went along. Paul Theofanous wanted to

get together to tell us how interested IMG was in our career, which made us feel added pressure. We had publicity pictures

taken at eight o’clock the night before the competition, when I’d normally have been either resting or already in bed.