My Life So Far (35 page)

After several days I was able to get up. I wanted to lose the weight I’d gained in time for the upcoming film, so I started doing ballet pliés in the bathroom. But this caused me to hemorrhage, which meant I had to stay in the hospital for a week, seeing Vanessa only when they’d bring her to me to feed.

Stuck in a hospital. Sick, like my mother!

I was miserable. I did breast-feed a little, but the nurses were giving Vanessa supplements (without asking me), so it wasn’t altogether successful—which made me feel I was already failing as a mother.

After a week Vadim came to take us home. There were paparazzi outside the clinic taking pictures, some of which I still have. I am looking down at the baby in my arms, and the uncertainty on my face reflects something that Adrienne Rich wrote in her book about motherhood,

Of Woman Born,

“Nothing could have prepared me for the realization that I

was

a mother . . . when I knew I was still in a state of uncreation myself.”

A friend had recommended a cockney nanny named Dot Edwards, who had flown in from London and was waiting at the farm when we arrived. She took over the responsibilities of caring for Vanessa, just as nannies had cared for me and my brother. Wasn’t it the way things were done? I went to bed and cried for a month (like my mother), not knowing why. I felt that the floor had dropped out from under me. Vanessa knew it, I swear. She knew something was wrong and would cry whenever she was with me. Dot said it was colic, but I knew better.

In trying to understand my mother and how her state of mind at my birth might have affected me, I have learned a lot about postpartum depression: how, after the birth of a child, not just the body but the psyche is opened to the reliving of early, unresolved injuries; how these “memories” can penetrate to the deepest psychic fault line, causing profound grief. Perhaps after Vanessa’s birth I was reexperiencing the sadness and aloneness I had felt as an infant. But, of course, nobody knew much of anything about PPD back then, so instead of seeing my depression as a not-so-unusual phenomenon (exacerbated by the horrid forceps), I just felt that I had failed—that nothing was turning out the way it was supposed to, not the birth, not the nursing, not my feelings for my child or (it seemed) hers for me. I don’t know how women with PPD manage to cope when they can’t afford the kind of help I had in Dot. I think this is partly why I would later find myself focusing on working with young, poor mothers and their children.

Unable to nurse successfully, I gave up and turned to Adelle Davis (the first mainstream health food proponent) for advice about what a baby should drink.

When Vanessa was three months old we went to Hollywood, where I began preparations for

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

I took my baby to a traditional pediatrician in Beverly Hills and told him that I was concerned because she was always throwing up.

“What formula are you giving her?” the doctor asked.

“Well, what Adelle Davis recommends,” I answered. “Dessicated baby veal liver, cranberry juice concentrate, yeast, and goat’s milk. Of course we have to make the holes in her bottle larger. . . .”

He was speechless for a moment, then he broke out laughing.

I switched to Similac formula, again feeling that I’d failed.

CHAPTER TWO

THEY SHOOT HORSES, DON’T THEY?

It is hard work to control the workings of inclination and turn the bent of nature; but that it may be done, I know from experience. God has given us, in a measure, the power to make our own fate.

—C

HARLOTTE

B

RONTË,

Jane Eyre

T

HE ORIGINAL WRITER

/

DIRECTOR OF

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

was fired and replaced by a young director named Sydney Pollack, who called to ask if he could come over and discuss the script with me. I remember sitting with Sydney at our house and his asking me what I thought the script problems were and would I read the original book carefully and then talk with him about what was missing in the adaptation. Wonderful Sydney had no idea what this meant to me. Naturally I had discussed script problems with Vadim on the movies we had made together, but this was different. This was a director who was actually

seeking

my input. It was a germinal moment. I began to study the book in ways I hadn’t before—identifying moments that seemed essential not just to my character but to the movie as a whole, making sure everything I did contributed to the central theme. This was the first time in my life as an actor that I was working on a film about larger societal issues, and instead of my professional work feeling peripheral to life, it felt relevant.

They Shoot Horses

was an existential story that used the marathon dances of the Depression era as a metaphor for the greed and manipulativeness of America’s consumer society. The entire story took place in a ballroom on the Santa Monica Pier, a place that had been a part of my childhood, where marathon dances had actually been held. During the Depression contestants in the marathons, hoping to win prizes, would dance until they literally dropped from exhaustion, while crowds of people sitting on bleachers would cheer their favorite couples and thrill at the sight of dancers collapsing, hallucinating, going crazy—like spectators at the Roman Colosseum watching Christians being thrown to the lions. From time to time there would be a race around the ballroom to wear the contestants down and speed up the eliminations. After several hours the dancers would get a ten-minute rest break, and then they’d go back out on the floor.

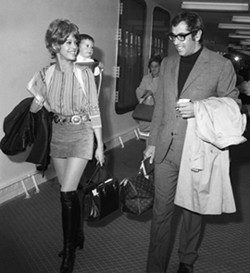

On the

Ile de France

in 1969. I’m wearing a wig, and Dot is following just behind Vadim.

(AFP/Getty Images)

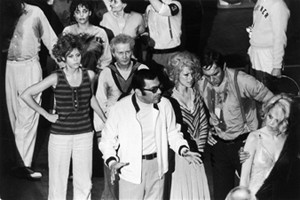

As Gloria in

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

(Photofest)

Sydney Pollack directing

Horses.

Behind him, left to right: me, Red Buttons, and Susannah York in the lower-right-hand corner.

The ballroom had been re-created on a sound stage. Red Buttons would be my partner for several scenes. He and I decided to see what it felt like to dance on the set until we couldn’t stand up, as we would in the movie. We were more or less fine for a day or so, then we got so tired we had to hold each other up as we shuffled around. Neither Red nor I could understand how people had gone on for weeks at a time. After two days I began hallucinating. My face was right up against Red’s cheek, and when I opened my eyes I could see every pore of his skin; I realized that although he was a good deal older than me, his skin was remarkably young.

When we’d decided we’d had enough, that it was time to go home, I told him how impressed I was with his skin, and he told me it was due to a nutritionist, Dr. Walters, in the San Fernando Valley.

I promptly made an appointment to see the doctor, who gave me a thorough examination, which included taking samples of my hair and skin. A week or so later he put me on a complicated regimen of vitamin supplements, gave me a lot of little plastic jars to keep them in, and told me to mark each with “B,” “L,” and D,” for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. (I tell you this because those little plastic jars will resurface and get me into a lot of trouble!)

The film was a turning point for me, both professionally and personally. Sydney, having been an actor himself, is a wonderful actor’s director, and with his guidance I probed deeper into the character and into myself than I had before, and I gained confidence as an actor.

But as I grew stronger I felt a parallel weakening of my marriage, a growing dissatisfaction, and less willingness to swallow the hurt that Vadim’s drinking and gambling—not to mention the threesomes—caused me. But the idea of actually leaving him was still too hard to confront. I didn’t want to be alone. I still felt that it was my relationship with him, however painful, that validated me. What will I be without him? I won’t have any life. I had put so much into creating a life with him, fitting into

his

life, that I’d left myself behind. But who

was

“myself”? I wasn’t sure. And now we had this little girl together, and there was Nathalie, and the home I’d created and all those trees I’d planted. In addition to everything else, a divorce felt like such an admission of—yes—failure. And I’d wanted so much to do better than my dad at marriage.

One day I was driving to the studio and, without noticing, ended up hours to the north, without knowing how I got there. I was having a mini breakdown, I think. Naturally I drew on my real-life anguish for all it was worth to feed my role as Gloria, the suicidal character in the movie who asks her dance partner to shoot her, the way they shoot horses with a broken leg.

I would spend days and nights living at the studio instead of going home to Malibu, partly because I wanted to enhance my identification with Gloria’s hopelessness and partly because I just didn’t want to go home to Vadim. I had a playpen set up in my dressing room and would have Dot bring Vanessa to me so I could feed her and sing to her. I knew only one lullaby from my own childhood, so I got a record of all the best lullabies and memorized them all. Then I would sing them one after the other to her (she sings them to her children now). In spite of my feelings of failure as a mother, giving birth—and to a

girl—

made me feel more connected to life and to femaleness in a way that was all my own, not a reflection of my husband. Even my body seemed to fall into a new, more graceful alignment.

One of the actors on the film was Al Lewis, who’d become famous as Grandpa in

The Munsters

on television. He would spend hours in my dressing room talking about social issues, and in particular about the Black Panther Party. Marlon Brando had taken up their cause and Al thought that I should, too. I remembered the conversations back in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, while filming

Hurry Sundown,

when I’d first learned about black militants. Al talked to me about the Panthers who’d been killed in Oakland, how others were being framed and put in jail with unreasonably high bail, and how Brando was helping to raise bail money and get lawyers.