Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (52 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

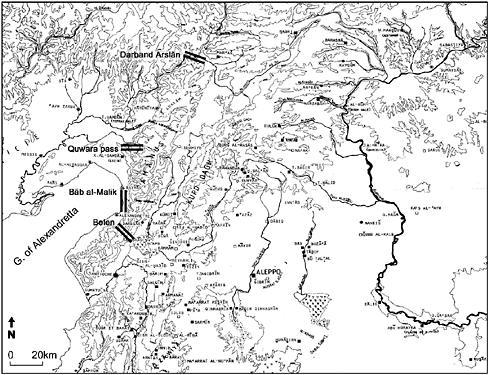

Map 3.1

The four main mountain passes in Cilicia

The Crusader enclaves

The thee Crusader entities, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Tripoli, and the Principality of Antioch, formed enclaves that broke the geographical and political continuity along the Syrian littoral within the Sultanate. The attempts of the lkhānids to form an alliance with the Pope and with European monarchs in order to receive their support in fighting the Mamluks constituted a threat that hovered over the Sultanate and could not be ignored. In addition, the Principality of Antioch and the other Frankish settlements in Syria occasionally cooperated with the Īlkhānids and spied on their behalf.

22

By the early 1270s the Crusader kingdom had lost large parts of their territories along the coast. The aggressive policy of Baybars was carefully followed by his successor. Except for Chastel Pelerin and Acre, most of the fortresses and towns along the southern coast and further inland had capitulated by 1265. Antioch fell in 1268, Qalāwūn sacked Tripoli in 1289 and with it fell many of the northern coastal towns and strongholds, among them Marqab. Acre, the last important city, was besieged in 1291 and fell to al-Ashraf Khalīl. The destruction of the Crusader enclaves eventually gave the Sultanate political and geographical continuity from Cairo to Aleppo. These changes had a direct influence on the distribution of fortresses in the Levant; some of the strongholds conquered and rebuilt in the early decades gradually lost their military importance due to geopolitical changes throughout the region.

23

To build or not to build: the military, political and economic priorities that dictated which fortresses should be reconstructed

Throughout the second half of the thirteenth century Mamluk military activity barely ceased. The Mamluk forces in Syria and the sultan’s army in Cairo were constantly employed in siege warfare, raids and full-scale battles. Though an efficient and mobile force, the army could not fight on several fronts simultaneously.

Each of the political entities concerned – the Franks, Īlkhānids, Armenians and – had its own interests as well as its own army. Both the size of each entity’s army and methods of warfare were quite different. The ranks, at this stage, fought mainly from within their fortresses. They carried out raids in their vicinity but rarely initiated open-field battles. This defense policy which relied on strongholds and fortified cities was carefully followed until the end of the Crusader period.

– had its own interests as well as its own army. Both the size of each entity’s army and methods of warfare were quite different. The ranks, at this stage, fought mainly from within their fortresses. They carried out raids in their vicinity but rarely initiated open-field battles. This defense policy which relied on strongholds and fortified cities was carefully followed until the end of the Crusader period.

24

In contrast to the Mamluk ability to organize efficient relief forces, throughout most of the second half of the thirteenth century each Frankish stronghold had to stand and defend itself, knowing that relieving armies were rarely available. Although they were well versed in the art of siege warfare, Frankish forces could not threaten Mamluk strongholds without considerable assistance from an outside military ally.

One of the few Frankish assaults on a Mamluk fort was led by Prince Edward of England, who tried to conquer Qāqūn in 1271. Even when a considerable reinforcement had arrived from Europe, little effort was made to join forces with the Īlkhānid army or the Armenians,

25

and even modest ambitions such as capturing Qāqūn (by far one of the smallest Mamluk strongholds) were unsuccessful. The English prince finally returned home without achieving any of his aims.

The Īlkhānid army, on the other hand, was highly mobile in comparison to the Franks, the Armenians and the Mamluks. It did not suffer from a lack of manpower and could summon a large force. Mounted archers composed the core of the army and fighting in the open field was clearly preferred to any other form of combat. The ranks were familiar with this form of warfare though they did not adopt it in the East. As far as fortresses were concerned, the Īlkhānids did not follow the practice of establishing strongholds. Camps were set up in the field and packed and folded when the army was ready to move. Thee are no contemporary accounts attesting to Īlkhānids building or restoring fortifications along the Euphrates and there appears to have been no large permanent Mongol presence along the eastern frontier.

26

The third army that often clashed with Mamluk forces throughout this period was the Armenian, which combined various elements and styles of warfare acquired from the Byzantine Empire, Central Asia and Western Europe. It was composed of mounted archers who rode beside heavily armoured knights.

27

The kingdom was guarded and secured by fortresses built along mountain passes, central junctions and the Mediterranean ports.

28

According to Molin the Armenians knew that their military forces were not sufficient to encounter the Mamluks on the open battlefield. They therefore chose strongholds in mountain areas to lure the Mamluk forces into rough, steep and forested terrain that would be difficult for a large mounted force to negotiate.

29

After 1264, the Armenians never initiated raids or crossed into Mamluk territory of their own accord, though they never avoided or refused any of the Īlkhānids’ invitations to join forces.

Among all these armies the were exceptional. This small group established itself in a chain of fortresses along the southern Nasseriyya Mountains. Their methods of warfare and their military activities were based on a small group of trained assassins who were sent out to murder carefully chosen political, religious and military leaders.

were exceptional. This small group established itself in a chain of fortresses along the southern Nasseriyya Mountains. Their methods of warfare and their military activities were based on a small group of trained assassins who were sent out to murder carefully chosen political, religious and military leaders.

30

Although this type of warfare did not cause mass destruction of villages, cities, crops and the like, it could easily destabilize the entire region.

31

The only army that had both the knowledge and the real capabilities of engaging in siege warfare and could threaten Mamluk fortifications was that of the Īlkhānids. While the Armenians supported and often joined Īlkhānid campaigns they could not mount a full scale siege with their own forces. The did not prossess a field army that could employ siege warfare methods. And, although the Franks had both the knowledge and the experience, they did not have sufficient manpower to carry out either long or short siege campaigns.

did not prossess a field army that could employ siege warfare methods. And, although the Franks had both the knowledge and the experience, they did not have sufficient manpower to carry out either long or short siege campaigns.

Unlimited variety

By the mid thirteenth century numerous fortresses were scattered throughout the region under Mamluk rule. The majority ere built in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries by the Ayyubids, the Franks, the Armenians, the and numerous local rulers. Points of particular military or economic significance, sites that overlooked central roads and junctions as well as strategically important mountain passages and fords – most such sites were fortified long before the Mamluks came to power. Some fortresses represented the finest and most advanced military architecture of the time. The nature of these strongholds, the quality and standard of construction depended on the importance rulers ascribed to the site. One should bear in mind, however, that the importance of fortresses changed in accordance with political developments, which often brought about significant modifications in the layout of frontiers and borders.

and numerous local rulers. Points of particular military or economic significance, sites that overlooked central roads and junctions as well as strategically important mountain passages and fords – most such sites were fortified long before the Mamluks came to power. Some fortresses represented the finest and most advanced military architecture of the time. The nature of these strongholds, the quality and standard of construction depended on the importance rulers ascribed to the site. One should bear in mind, however, that the importance of fortresses changed in accordance with political developments, which often brought about significant modifications in the layout of frontiers and borders.

The first impression one gets from a preliminary survey of Baybars’ military activity is that the Mamluks’ chief aim during their first decades in power was to destroy as many fortresses as they could, thus reducing their adversaries’ hold on the region. It seems that what guided Baybars was the knowledge that a considerable amount of time and money would be required to rebuild a fortress whose towers and walls were badly damaged, food, grain and weapons supplies burnt or confiscated and whose garrison was put to death or taken into captivity.

More than any other political entity, the Franks, consistently lacking human resources, found it increasingly difficult to man and replace garrisons in fortresses they had lost. Even where the archaeological remains show that the fortress was not completely destroyed, the damage to the infrastructure was enough to prevent the Franks from returning to it – they simply did not have the forces and funds to re-take and repair their strongholds. This lack of a central organized regime and of unity

amongst their forces hampered any attempt to regain lost territory. Thus, fortresses taken by the Mamluks were never recovered by the Franks.

In contrast, the Armenians in Cilicia managed to recover their fortresses, via diplomatic negotiations or by besieging and re-taking them in battle. They quickly rebuilt, manned and supplied them. In one case where funds were in short supply they appealed to the Pope. The fortifications at the port of Ayās, in need of reconstruction after a severe Mamluk assault, were restored using papal funds.