Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (37 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

Harlan had been appointed to the Court by President Eisenhower fifteen years earlier and had a reputation as a fair-minded jurist, despite his Republican views.

“He had been a high ranking officer in World War II so he definitely supported the military,” says one of his clerks at the time, Thomas Krattenmaker. “But he was very torn by the Vietnam War, he thought it was an ill-defined adventure. He was not the kind of guy to say ‘my country right or wrong.’”

A short while previously, Harlan, who was dying of cancer, had demonstrated a strong commitment to free speech in the case of

Radich vs. New York,

in which the proprietor of a Manhattan art gallery had been convicted of displaying American flags in a “lewd, vulgar and disrespectful way.” The flags were actually thirteen different impressionistic sculptures, each portraying the Stars and Stripes in the shape of a penis. Harlan presumed the display was a protest against the war and lobbied hard—unsuccessfully—to convince his colleagues to overturn the conviction.

It was with this sort of open mind that Harlan took home

Message to the Blackman in America.

By the next morning, he had done a complete about-face. Without informing his colleagues or the Chief Justice, he immediately set about drafting a memo arguing that the government had mistakenly painted Ali as a racist and misinterpreted the doctrine of the Nation of Islam pertaining to Holy Wars, even though the Justice Department’s own hearing examiner, Judge Lawrence Grauman, found that Ali was sincerely opposed to all wars at the original hearing in 1966. In that decision, Grauman ruled, “I believe that the registrant is of good character, morals and integrity, and sincere in his objection on religious grounds to participation in war in any form. I recommend that the registrant’s claim for conscientious objector status be sustained.”

If the government had followed Judge Grauman’s advice at the time, Harlan believed, this whole case could have been avoided. In conversations with his colleagues, Harlan had hinted that he was having second thoughts about the case, but none were aware of how serious he was.

“The most important thing that caused him to change his mind was that he now understood the Muslim concept of Holy War,” explains Krattenmaker. “Basically, a Holy War was more of a purely philosophical religious speculation. Ali was saying that if Allah came down and commanded it, he would fight a war. You knew that wasn’t really going to happen. It was almost exactly the reason the Jehovah’s Witnesses won their conscientious objector cases during World War II.”

On June 9, Harlan shocked the Chief Justice by sending him a copy of his memo along with the following cover letter:

Dear Chief:

My original Conference vote was to affirm, and it was of course on that basis you assigned the opinion to me. As I tentatively indicated to the Conference a week or so ago and in later conversation with you, subsequent work on such an opinion brought me serious misgivings, and I am now convinced the conviction should be reversed.

In his memo, Harlan cites the religious doctrine of the Nation of Islam, quoting Elijah Muhammad’s

Message to the Blackman in America,

which states:

The very dominant idea in Islam is the making of peace and not war; our refusing to go armed is our proof that we want peace. We felt that we had no right to take part in a war with nonbelievers of Islam who have always denied us justice and equal rights; and if we were going to be examples of peace and righteousness (as Allah has chosen us to be) we felt we had no right to join hands with the murderers of people or to help murder those who have done us no wrong.…We believe that we who declared ourselves to be righteous Muslims should not participate in any wars which take the lives of humans.

The justice believed this passage proved that Black Muslims were legitimately opposed to all wars on religious grounds. But in recommending against Ali’s conscientious objector claim, the government had maintained his objection rested “on grounds which primarily are political and racial. These constitute only objections to certain types of war in certain circumstances, rather than a general scruple against participation in war in any form.” In his memo, Harlan called these arguments “misreadings and overdrawings.”

Harlan’s switch meant the justices were now deadlocked four to four. A tie vote meant that Ali would still go to prison. But Burger was furious, telling one of his clerks that Harlan had become “an apologist for the Black Muslims.” If Harlan had his way and stressed the government’s twisting of the facts, Burger believed, it might mean that all Black Muslims would be eligible for conscientious objector status.

Burger was among the most conservative of the justices and strongly supported President Nixon’s obsession with stifling anti-war dissent. The day after the Court heard arguments in Ali’s case, the chief justice accepted an emergency petition from the Justice Department to evict from their makeshift campsite on the Washington Mall hundreds of peaceful army veterans who were protesting the war. Burger upheld the government’s claim that the veterans represented a threat to national security.

Neither Burger nor the other members of the original majority had any intention of changing their vote. If the deadlock stood, Ali would go to prison. A tie vote is not accompanied by a decision, so he would never know why he lost.

Justice Potter Stewart believed a clear injustice was about to be perpetrated. First, Ali had been convicted for political reasons; now the Court was about to send him to prison because they were afraid of the political consequences of setting him free.

Meanwhile, Ali awaited the Court’s decision with the same aplomb he had displayed for the last four years. “If the judges look at me in what I believe, they’ll vindicate me,” he told an interviewer. “But if they send me to jail, I’m not going to leave the country. You don’t run away from something like that. When you go to jail for a cause, it’s an honor. If I have to go, I’ll be a famous prisoner.”

Stewart and his clerks studied the case carefully until they discovered a compromise alternative.

In order to satisfy a claim for conscientious objection, an applicant must satisfy three basic requirements. He must show that he is conscientiously opposed to war in any form. He must show that this opposition is based on religious training and belief, as interpreted in two key Supreme Court rulings. And he must show that his objection is sincere.

In 1966, after a hearing officer ruled that Ali’s claim was sincere, the Justice Department sent a letter to the Selective Service Board—which eventually ignored the hearing officer—disputing his finding. In the letter, the Department implied that it had found Ali had failed to satisfy each of the three tests of conscientious objection.

To the requirement that the registrant must be opposed to war in any form, the letter said Ali’s beliefs “do not appear to preclude military service in any form, but rather are limited to military service in the Armed Forces of the United States.”

To the requirement that the registrant’s opposition must be based on religious training and belief, the letter said that Ali’s “claimed objections to participation in war insofar as they are based upon the teachings of the Nation of Islam, rest on grounds which primarily are political and racial.”

To the requirement that a registrant’s opposition to war must be sincere, the letter contained several disparaging paragraphs reciting the timing and circumstances of Ali’s conscientious objector claim and concluded that “the registrant has not shown overt manifestations sufficient to establish his subjective belief where his conscientious-objector claim was not asserted until military service became imminent.”

Stewart pointed out that, in oral arguments before the Court, Solicitor General Griswold himself had conceded that Ali’s beliefs were based upon “religious training and belief.” Presenting the government’s case against Ali, Griswold had been asked by Justice Douglas whether he personally believed Ali had been sincere in his beliefs. He admitted that he believed so, which proved to be a critical legal lapse.

This kind of mistake by an accomplished legal scholar like Griswold—the government’s highest-ranking prosecutor—is unusual. It is possible that, because of the changing political winds since the original conviction and growing public sympathy for Ali, Griswold deliberately decided to give the Court an “out”—an excuse to reverse the conviction and avoid the inevitable outcry that would have resulted from Ali’s imprisonment.

Stewart had found his compromise. “Since the Appeal Board gave no reasons for its denial of the petitioner’s claim,” he wrote to his colleagues, “there is absolutely no way of knowing upon which of the three grounds offered in the Department’s letter it relied. Yet the Government now acknowledges that two of those grounds were not valid and… the Department was simply wrong as a matter of law in stating that the petitioner’s beliefs were not religiously based and were not sincerely held.”

Stewart’s clerks spent all night researching court precedents until they found the 1955 case of

Sicurella vs. the United States,

which involved a similar error in an advice letter by the Justice Department. In that case, the Court ruled the error was sufficient to overrule a conviction.

This technicality—the Justice Department’s wrong advice to the Appeal Board—was sufficient excuse for every justice except Burger to reverse Ali’s conviction. Even the previously reluctant justices were willing to set Ali free as long as it didn’t give carte blanche for every Black Muslim to evade the draft.

“It’s what Justice Harlan always called a ‘peewee,’” explains his former clerk Krattenmaker. “It was a way of correcting an injustice without setting a precedent and changing the law.”

The only holdout was the Chief Justice. According to Woodward and Armstrong in

The Brethren,

the compromise left Burger with a problem. If he dissented, his might be interpreted as a racist vote. He decided to join the others and make it unanimous. An eight-to-nothing decision would be a good lift for black people, he concluded somewhat patronizingly.

The Court’s decision was released on June 28, 1971. Gene Dibble was with Ali in Chicago when his newly vindicated friend heard the news. “We were driving in his car and we stopped at a store,” he recalls. “When he stepped out of the car, a guy came running out of the store and said he just heard on the radio that the Court had freed him. For once, Ali didn’t know what to say. I could tell he was happy. I know he thought he was going to prison.”

A swarm of reporters was waiting for the exonerated boxer at his motel, anxious to get his reaction to the news.

“It’s like a man’s been in chains all his life and suddenly the chains are taken off,” he told them. “He don’t realize he’s free until he gets the circulation back in his arms and legs and starts to use his fingers. I don’t really think I’m going to know how that feels until I start to travel, go to foreign countries, see those strange people in the street. Then I’m gonna know I’m free.”

A reporter asked whether he would take legal action to recover damages from those who hounded him into internal exile. His answer displayed the same dignity he had maintained through his seven years as a national pariah.

“No. They only did what they thought was right at the time. I did what I thought was right. That was all. I can’t condemn them for doing what they think was right.”

Ali’s greatest fight was over. Now that American society had begun to catch up to him, now that he had stripped it of some its prejudices and ignorance, he could turn back, rehabilitated, to what had brought him fame in the first place. While his most glorious days as a boxer still lay ahead—his recapturing of the heavyweight crown still to come—as a fighter in the world outside the ring, as a catalyst for change, and as a hero to his people, Muhammad Ali would never have the same impact again.

AFTERWORD

The Legacy

T

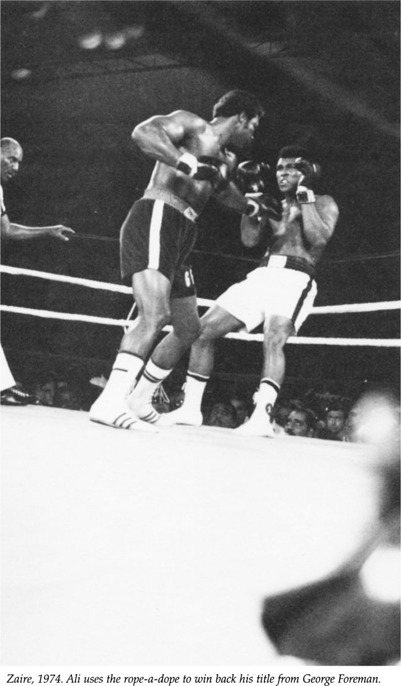

HROUGH THE AFRICAN NIGHT CAME

the repeated cries, “Ali Bomaye! Ali Bomaye! (Ali, kill him!).” In the ring below, George Foreman’s supposedly indomitable punching power was being thwarted by Ali’s improvised rope-a-dope strategy, designed to exhaust the powerful champion.

In the weeks leading up to the fight, he had signalled a return of the old Ali, promising the skeptics he was in top form. “I rassled an alligator, I done tassled with a whale/I handcuffed lightening/threw thunder in jail. That’s bad! Only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone/I’m so mean, I make medicine sick!”

Behind the tallyhoo, however, was an accute understanding of the significance of the fight and what it meant for so many.

“I’m going to win the fight for the prestige,” he vowed, “not for me but to uplift my brothers who are sleeping on concrete floors today in America, black people on welfare, black people who can’t eat, black people who have no future. I want to win my title so I can walk down the alleys and talk to wineheads, the prostitutes, the dope addicts. I want to help my brothers in Louisville, Kentucky, in Cincinnati, Ohio, and here in Africa regain their dignity. That’s why I have to be a winner, that’s why I’ll beat George Foreman.”