Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (31 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

The Supreme Court could have overturned Ali’s conviction on this basis alone. Instead, it granted him a different form of reprieve. On March 11,1969, the Court ruled that Ali’s case would be sent back to a lower court to determine if the wiretaps had had any influence on his prosecution.

“It wasn’t the best thing which could have happened,” says his lawyer Charles Morgan, “but it kept him out of prison and gave us another chance to pull something out of our hat.”

Ali’s new hearing was scheduled for Federal District Court on June 4,1969. Two days before the hearing was scheduled to begin, Morgan filed a motion demanding the government produce complete records of the wiretap information against Ali or drop the case. The U.S. Attorney agreed to allow Morgan to inspect four of the five transcripts, but the fifth was being withheld “for national security.”

Two days later, the hearing got underway with an explosive revelation. Under examination by Charles Morgan, FBI agent Robert Nichols took the stand and testified that the Bureau had maintained a telephone surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr. for several years before the civil rights leader’s assassination. For the many people who had long suspected that King was being monitored, this represented the first official confirmation.

Nichols then produced the transcript that affected Ali’s case. It contained a condensation of a September 1964 telephone conversation between Ali and King that had been initiated by lawyer Chauncey Eskridge, who represented the two men. It read, in sum:

Chauncey to MLK, said he is in Miami with Cassius, they exchanged greetings. MLK wished him well on his recent marriage. C. invited MLK to be his guest at his next championship fight. MLK said he would like to attend. C. said that he is keeping up with MLK, that MLK is his brother and is with him 100 percent but can’t take any chances and that MLK should take care of himself, that MLK is known worldwide and should watch out for them Whities, said that people in Nigeria, Egypt, and Ghana asked about MLK.

But Ali’s lawyer Chauncey Eskridge, who had also represented King, then testified that he had placed this particular call from Ali’s Miami home to Dr. King’s home in Atlanta, and that Ali had talked from an extension. He said the conversation had lasted forty-five minutes and included a discussion about Ali’s religious activities. This prompted Morgan to demand a complete transcript of the entire conversation; however, the FBI agent claimed the original recording had been destroyed.

On the initial copy provided to the court, the FBI had altered the document to take out Nichols’s handwritten name and remove the comma at the end of the transcript, to make it appear that the conversation was much shorter than it had, in fact, been.

“They were committing legal fraud,” recalls Morgan. “Luckily we caught them at it and we forced them to produce the original log. But we still only got ten lines of a forty-five-minute conversation.”

Among the other conversations the FBI released were several between Ali and Elijah Muhammad, whose phone had been bugged since 1960. In one, the Messenger told Ali that he would “not be a good Minister” until he gave up boxing.

The fifth conversation remained a mystery. The judge concurred with the U.S. Attorney that divulging its contents would compromise “national security,” a decision that helped fuel rumors that the conversation involved a member of a foreign government. If this was indeed the case, its disclosure would confirm that the U.S. government was illegally bugging foreign embassies, which would have resulted in a highly embarrassing international incident.

The next day, FBI agent Warren L. Walsh testified that two of Ali’s bugged conversations had been sent from the FBFs Phoenix office to the Bureau’s office in Louisville, the location of Ali’s draft board. But Oscar Smith, former head of the Justice Department’s Conscientious Objector Section—the man who ruled against Ali’s conscientious objector claim—denied that he had ever heard of the monitored conversations.

This was enough for Judge Joe Ingraham, who ruled the wiretap evidence was irrelevant to Ali’s draft case and re-sentenced the boxer to five years in prison and a ten-thousand-dollar fine. Before handing down his sentence, the judge asked if Ali had anything to say.

“No, sir,” came the polite reply. “Except I am sticking to my religious beliefs. I know this is a country which preaches religious freedom.”

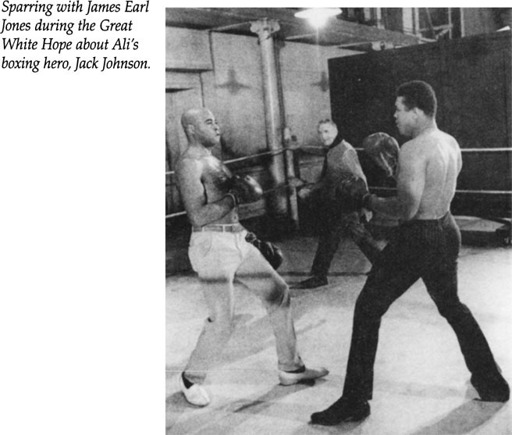

Soon after the hearing, Ali was invited to the opening of a new Broadway play called

The Great White Hope,

with James Earl Jones starring as Jack Johnson. As he approached the theater, Ali looked up at the blown-up photograph of a black man with a shaved skull in bed with a white woman.

“So that’s Jack Johnson,” he said to himself, pursing his lips in a silent whistle. “That was a b-a-a-a-d nigger!”

As the curtain rose, Jones appeared on stage in the persona of the notorious black boxer, mocking sportswriters at a press conference. He told the reporters that the reason he smiled so much in the ring was because “Ah like whoever ah’m hitting to see ah’m still his friend.” When Jones told a white opponent that he looked as if he were “about ta walk da plank,” Ali laughed and said to his seatmate, “Hey! This play is about me. Take out the interracial love stuff and Jack Johnson is the original me.” It appeared to be the first time Ali had ever made the connection.

At the end of the first act, Johnson decides to leave the country rather than be sent to prison and be stripped of the title he won in the ring.

As Ali stood in the lobby signing autographs during intermission, he said, “Hey, that Jack Johnson just gave me an idea.”

“If you went to Canada,” said a white middle-aged businessman, “I wouldn’t blame you.”

“Sssh,” Ali said, looking around in mock terror and then smiling. “I couldn’t do that. They’d raise hell with my people.”

A while later, he repeated his joke about going to Canada to a young black woman.

“Oh don’t do that,” she pleaded. “We need you

here

in this country.”

When a reporter asked him if he could ever really contemplate fleeing the country, he said, “You understand? They done picked up my passport and took my job. But I couldn’t leave this country like Jack Johnson did even if I wanted to. But you know I’ve been visiting jails just to get used to it. Man, that is a bad place, jail. All cooped up, nothing to do, eating bad food. Oh, man.”

After the play, Ali visited the cast backstage. He said to Jones, “You know, you just change the time, the date, and the details and it’s about me.”

“Well, that’s the whole point,” said the actor.

Ali’s tone became somber. “Only one thing is bothering me.”

“What?”

“Me,” he said. “Just what are they gonna do fifty years from now when they gotta write a play about me.” He paused and thought about it. “I just wish I knew how it was gonna turn out.”

CHAPTER NINE:

Return from the Wilderness

B

Y THE SPRING OF

1969, two years of exile from the ring had left a mark on the marginalized champion. His grueling lecture tours brought in barely enough money to pay his outstanding lawyers’bills and his recent week-long jail stint had forced him to confront the reality of what likely lay ahead. He had long since been dismissed as a boxing footnote by the time his old friend Howard Cosell invited him to appear for an interview on ABC’s

Wide World of Sports

in early April.

Revisionist history notwithstanding, Cosell had yet to publicly call for the reinstatement of Ali’s heavyweight title almost two years after he had refused induction. During the course of the interview, however, he asked his old verbal sparring partner if he had any desire to return to boxing. Ali’s answer was offhand and curt. Still, it was enough to tear apart his world.

“Yeah, I’d go back if the money was right,” he responded. “I have a lot of bills to pay.” As Ali spoke, Elijah Muhammad watched the interview at his Chicago mansion with his lieutenant John Ali. That week’s edition of

Muhammad Speaks

had already been sent to the printers. The Messenger made a phone call and stopped the presses. Two days later, the Nation’s 500,000 members were stunned by the front-page headline,

WE TELL THE WORLD WE’RE NOT WITH MUHAMMAD ALI.

In a signed editorial, Elijah wrote:

Muhammad Ali is out of the circle of the brotherhood of the followers of Islam under the leadership and teaching of Elijah Muhammad for one year. He cannot speak to, visit with, or be seen with any Muslim or take part in any Muslim religious activity. Mr. Muhammad Ali plainly acted the fool. Any man or woman who comes to Allah and then puts his hopes and trust in the enemy of Allah for survival is underestimating the power of Allah to help them. Mr. Muhammad Ali has sporting blood. Mr. Muhammad Ali desires to do that which the Holy Qur’an teaches him against. Mr. Muhammad Ali wants a place in this sports world. He loves it.

The next edition of the newspaper took the shocking punishment a step further, announcing that the Nation’s most famous recruit would be referred to by his old slave name Cassius Clay rather than be recognized “under the Holy Name Muhammad Ali.”

The paper carried a statement from the Messenger’s son, Herbert Muhammad, that he was “no longer manager of Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay)” and furthermore that he was no longer “at the service of anyone in the sports world.”

Sensitive to the widespread assumption that the boxer’s huge fortune had been plundered by the Nation of Islam, John Ali wrote that the champion’s need to fight to pay off debts resulted from his own “ignorance and extravagance” by failing to follow the teachings of Elijah Muhammad, who advised all of his disciples to be prudent in handling their money.

“Neither Messenger Muhammad, the Nation of Islam, nor the Muslims have taken any money from Muhammad Ali,” stated the movement’s National Secretary. “In fact, we have helped Muhammad Ali. Even Muhammad Ali’s sparring partners made better use of their monies than Muhammad Ali, who did not follow the wise counsel of Messenger Muhammad in saving himself from waste and extravagance.”

It would be the last reference to Muhammad Ali in the newspaper for almost three years. It is difficult to accurately gauge the Nation’s motives in disassociating itself from its most celebrated member, but Elijah Muhammad’s biographer Claude Clegg doesn’t buy the Messenger’s official explanation. “That Ali’s stated desire to be financially rewarded for his boxing talents was suddenly offensive to Muhammad is not credible,” writes Clegg. “For the past five years, the fighter had made his living in the sport. By 1969, Muhammad’s tolerance of the exceptionality of Ali among his followers was simply no longer necessary. In the era of Black Power, the boxer was no longer an essential factor in the appeal of the Nation to young African Americans, and his ouster would not have a significant impact on membership. On another level, the suspension of Ali was reminiscent of the isolation of Malcolm X during 1964. It seemed to raise many of the same issues of authority, generational tensions, and jealousies. Arguably, the punishment was meant to be a reassertion of Muhammad’s dominion over the Nation—a reminder to followers who had become a bit too enamored of Ali.”

According to Jeremiah Shabazz, one of Ali’s earliest spiritual advisers, the comment angered Muhammad, “because to him it was like Ali saying he’d give up his religion for the white man’s money.”

Eugene Dibble recalls his friend’s reaction to the suspension. “He was shattered. The Muslims were his life. First he got his title taken away and they threatened to send him to prison but that was nothing compared to his suspension from the Nation. He acted like a little boy who had been spanked for being bad.”

For years the Nation of Islam had controlled every facet of Ali’s life. Suddenly, he was on his own. Elijah Muhammad had been like a father to him—so much so that he had virtually shunned his own father for more than five years. Now Cassius Clay Sr. re-entered his son’s life and was shocked to discover his son’s financial state. This only confirmed his longstanding suspicion of the Muslims, who he believed had stolen his son’s money.

For his part, Ali was shaken by the suspension but believed it was just one more test by Allah. On the lecture circuit he continued to invoke the name of Elijah Muhammad and constantly praised his spiritual leader. He seemed to show genuine remorse for his words, but continued to call himself Muhammad Ali despite the Messenger’s prohibition.

“I made a fool of myself when I said that I’d return to boxing to pay my bills,” he told one student who asked about the suspension. “I’m glad he awakened me. I’ll take my punishment like a man and when my year’s suspension is over, I hope he’ll accept me back.”

Suddenly shorn of his Muslim entourage, Ali enlisted his old fight publicist Harold Conrad to drum up some paying gigs. The ever-struggling Ali had virtually disappeared from the national radar screen. Before long, though, appearances on national TV shows such as

What’s My Line?

and

Memo Griffin

reminded Americans that Ali was still around and still defiant.