Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (16 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

It took longer to sing the national anthem than it did for Ali to knock out Sonny Liston in the first round and prove the first fight was no fluke. Despite renewed speculation by Ali’s detractors that the challenger had taken a dive—the FBI investigated the rumors and found no merit to them—it was clear to the boxing world that Muhammad Ali was a force to be reckoned with.

“Even those who didn’t like him—and there were plenty—had to respect him after the second Liston fight,” says Robert Lipsyte. “For a little while at least, people stopped dwelling on all the controversy and began to admire his boxing skills.”

A month after the Liston fight, Ali had his marriage to Sonji Roi annulled on the grounds that she had failed to follow the tenets of the Muslim religion. To many, this signaled the increasing grip of the Nation of Islam over every facet of his life. And not without some foundation: Elijah Muhammad had assigned his son Herbert to handle Ali’s business affairs, and a large Muslim entourage traveled with the champion wherever he went.

“They’ve stolen my man’s mind,” Sonji charged after the annulment. “I wasn’t going to take on all the Muslims. If I had, I’d probably have ended up dead.”

Meanwhile, the boxing world searched in vain for somebody to send Ali back to oblivion. In Jack Johnson’s day, the call had gone out for a “white hope” to silence the upstart champion. Now a similar call went out but this time with an ironic twist. The challenger this time would have to be a black “white hope”—and it looked like there was only one man to fit the bill.

Floyd Patterson had been a popular heavyweight champion before he lost the title a few years earlier to Sonny Liston in a humiliating first-round knockout. A rematch between the two fighters had ended even more quickly. In marked contrast to Ali, Patterson was soft-spoken, humble, and well-loved by the black and white establishments. He had marched for integration with Martin Luther King Jr., moved into an all-white neighborhood before being hounded out by angry neighbors, and even married a white woman. As historian Jeffrey Sammons once observed, “Ironically in Jack Johnson’s era, Ali would have been the hero and Patterson the villain.”

Shortly after the first Ali-Liston fight, Patterson had drawn the battle lines by announcing his intention to “bring the title back to America.” This attack didn’t sit well with Ali, who countered, “If you don’t believe the title already is in America, just see who I pay taxes to. I’m an American. But he’s a deaf dumb so-called Negro who needs a spanking …. We don’t consider the Muslims have the title any more than the Baptists had it when Joe Louis was champ.”

Ali agreed to a title match with Patterson, vowing not to let “one old Negro make a fool of me.” Patterson, a Catholic, made much of his own religious ties, and the fight was billed as a modern-day holy war between the forces of Christianity and Islam, even though the real issues had more to do with racial ideology and patriotism than religion.

At a press conference, Patterson declared, “The Black Muslim influence must be removed from boxing. I have been told Clay has every right to follow any religion he chooses, and I agree. But by the same token, I have the right to call the Black Muslims a menace to the United States and a menace to the Negro race.”

While Ali surrounded himself with an entourage of Muslims, Patterson traveled with an array of civil rights workers, liberal whites, and celebrities—including Frank Sinatra, who supplied Patterson with his own personal physician. All were rooting for him to shut Ali up once and for all.

The spectacle was not lost on the outspoken champion, who was offended by Patterson’s constant invocation of his civil rights credentials. “When he was champion,” Ali charged, “the only time he’d be caught in Harlem was when he was in the back of a car waving in some parade. The big shot didn’t have no time for his own kind, he was so busy integrating. And now he wants to fight me because I stick up for black people.”

On November 22,1965, the two fighters took their holy war into the ring. Ali had never been known as a brutal fighter. His artistry in the ring regularly reminded observers why boxing was known as “the sweet science.” A few months before the Patterson fight, he had even publicly contemplated retiring from the sport, declaring, “I don’t like hurting people.” But the constant attacks against his religion and his character had taken their toll and he was clearly out for revenge. What seemed to irk him most was Patterson’s declaration that he would never call his opponent by his Muslim name. Addressing the challenger, he vowed to “give you a whipping until you call me Muhammad Ali.” Before the fight, he announced his intentions poetically:

I’m gonna put him flat on his back

So that he will start acting black.

Because when he was champ he didn’t do as he should.

He tried to force himself into an all-white neighborhood.

The fight was no contest. Yet rather than putting the outmatched Patterson flat on his back quickly, Ali toyed with him, inflicting one brutal punch after another—but always holding back from ending it so as to prolong the agony. Finally, the referee showed mercy on the ex-champ and ended the fight in the twelfth round. Shocked by Ali’s uncharacteristic cruelty, the media—even those few reporters previously sympathetic to him—turned against him.

Life

magazine called the fight “a sickening spectacle in the ring.”

In his black cultural manifesto

Soul on Ice

—written shortly after the Patterson fight—Eldridge Cleaver explained the outpouring of negative reaction against Ali. “Muhammad Ali is the first ‘free’black champion ever to confront white America,” he wrote. “In the context of boxing, he is a genuine revolutionary, the black Fidel Castro of boxing. To the mind of ‘white’ white America and ‘white’ black America, the heavyweight crown has fallen into enemy hands, usurped by a pretender to the throne. Ali is conceived as ‘occupying’ the heavyweight kingdom in the name of a dark, alien power, in much the same way as Castro was conceived as a temporary interloper, ‘occupying’ Cuba.”

At the time, only a handful of white reporters were willing to defend Ali. Although he wouldn’t use the same fiery rhetoric as Cleaver, Robert Lipsyte of the

New York Times

seemed to sense the parallels between Ali and Jack Johnson as far back as November 1965. Analyzing the mounting backlash against the champion, he wrote, “The public—through the press—was not ready to receive the antithesis of Louis and Patterson. Once before it had been presented with a nonconforming Negro champion, and society rejected, harassed, and eventually persecuted Jack Johnson.”

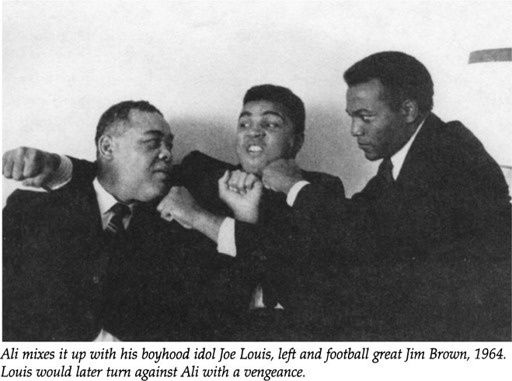

Nobody was more aware of Ali’s refusal to bow to the whims of the establishment than Joe Louis, who had perfected this role to become the first black man ever to be embraced by white America. Louis, who had once been Ali’s hero, had showed up in Patterson’s camp to give support to the challenger and took every opportunity to denounce Ali’s religion and fighting skills.

“Clay has a million dollars worth of confidence and a dime’s worth of courage,” he said. “He can’t punch; he can’t hurt you … I would have whipped him.”

Ali seemed to have Louis in mind when he later explained his rationale for speaking out. “When I first came into boxing, tied up as it was with gangster control and licensed robbers, fighters were not supposed to be human or intelligent… A fighter was seen but hardly heard on on any issue or idea of public importance. They could call me arrogant, cocky, conceited, immodest, a loud mouth, a braggart, but I would change the image of the fighter in the eyes of the world.”

The outpouring of disgust reached the highest levels of Washington, where President Johnson continued to receive hundreds of angry letters from citizens demanding to know why Ali wasn’t serving his country.

One of the most telling letters, indicating how little some racial attitudes had changed in a hundred years—not to mention the level of backwardness of the boxing establishment—was sent to General Lewis Hershey, director of the U.S. Selective Service, by the legal advisor to the World Boxing Association.

“I have watched with disgust the publicity surrounding the draft status of Cassius Clay, the boxer,” wrote Robert M. Summitt. “It now appears that Clay and his

owners axe

going to attempt further to evade the draft through your organization or even to the President of the United States [our italics].”

Americans still overwhelmingly supported the war in Vietnam. But, little by little, the first voices of dissent began to be heard. In June 1965, black civil rights activist Julian Bond—who had co-founded the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) five years earlier—was elected to a seat in the Georgia legislature in a special vote called to fill a vacancy. On January 6,1966—four days before Bond was scheduled to take his seat in the legislature—SNCC issued a “white paper” on the Vietnam War denouncing the United States for its conduct in the war and calling for resistance to the draft. “We are in sympathy with and support the men in this country who are unwilling to respond to the military draft which would compel them to contribute their lives to United States aggression in the name of the ‘freedom’we find so false in this country,” read the controversial paper. The media descended on Bond and asked him if he endorsed the SNCC manifesto. When he answered in the affirmative, he was widely lambasted as a traitor and a renegade. By a vote of 184 to 12, the Georgia House refused to seat him. Bond had marched with Martin Luther King Jr. on the bloody battlegrounds of the fight for civil rights and considered King his mentor. But in 1965, America’s most respected black leader had still not publicly come out against the war.

“At the time of the controversy, when they refused to seat me, it seemed like I was all alone,” recalls Bond. “Dr. King called me to express his support. He knew the war was unjust and he wanted to take a stand but his board at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) wouldn’t let him. President Johnson was supporting civil rights legislation and they didn’t want to alienate his administration.”

To challenge the legislature’s unconstitutional and undemocratic action, Bond hired noted civil liberties lawyer Charles Morgan Jr., who happened to sit on the Board of King’s SCLC. In doing so, he set in motion a freight train of events that would have monumental repercussions.

In July President Johnson had sent an additional 50,000 troops to Vietnam and announced that the monthly draft would increase to 17,500 men. A few years later, at the height of American escalation, the army would face severe shortages of manpower and—as in all wars — be forced to lower its eligibility standards. But in late 1965 there was still a massive draft pool to draw from, and the army could call on its most promising military recruits to fight what was still a small-scale war.

Still, inexplicably, the Pentagon issued a directive in November 1965 lowering the mental aptitude percentile on induction examinations from 30 to 15. Ali had scored 16 on his own exam two years earlier, a score that had rendered him unfit for military service. Now, by only one percentile, Ali was once again eligible for the draft.

“It was suspicious to say the least,” notes Robert Lipsyte.

Immediately, the director of Selective Service in Kentucky, Colonel James Stephenson, issued a statement that Ali was likely to be drafted soon because of the new criteria. It didn’t take long for the boxer’s supporters to voice their opinion of the lowered standards. “The government wants to set an example of Ali and they’ll even change their rules to get him,” declared Elijah Muhammad. “Muhammad Ali is harassed to keep the other mentally sleeping so-called Negroes fast asleep to the fact that Islam is a refuge for the so-called Negroes in America.”

But the skepticism wasn’t confined to Muslims. As far away as Vietnam, U.S. soldiers were following the controversy. Marine PFC Lee Rainey told the

Chicago Tribune,

“I thought Clay’s reclassification did have something to do with his involvement with the Black Muslims. He talked too much.”

On February 14, 1966, Ali’s lawyer, Edward Jacko, went before the Louisville draft board and requested a deferment for his client on a number of procedural grounds, including the financial hardship his family would suffer if he couldn’t box. The board rendered its decision three days later.

In Congress on the morning of February 17, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was debating an emergency appropriations bill to fund the escalating war in Vietnam. General Maxwell Taylor had been invited by the Senate to make the Johnson Administration’s case for more funding. One of the earliest critics of the war, Senator Wayne Morse of Indiana, told his colleagues that America shouldn’t be involved in the mounting conflict. “I want to prevent the killing of an additional thousands of boys in this senseless war,” he said, adding his opinion that Americans would surely repudiate the war before long.

“That, of course, is good news to Hanoi, Senator,” responded General Taylor, accusing Morse and other critics of helping to prolong the war.

“I know that is the smear tactic you militarists give to those who have honest differences of opinion,” Morse fired back, “but I don’t intend to get down in the gutter with you and engage in that kind of debate.”