More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory (28 page)

Read More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory Online

Authors: Franklin Veaux

Tags: #intimacy, #sexual ethics, #non-monogamous, #Relationships, #polyamory, #Psychology

Compulsory sharing is always a bit suspect. When others demand that we reveal ourselves, intimacy is undermined rather than strengthened, because something that is demanded cannot be shared freely as a gift. Intimacy is built by mutually consensual sharing, not by demands.

At the other extreme, some people insist on knowing absolutely nothing about a partner's other lovers. Not even how many, not even their names. These "Don't ask, don't tell" relationships raise troubling questions about boundaries, consent and denial. If we know nothing about a partner's other activities, we will find it difficult to make informed choices about our relationship—particularly the sexual aspects. "Don't ask, don't tell" relationships put outside lovers in an unenviable position too. Often such relationships include restrictions on calling a partner at home, and they almost always preclude visiting a partner at home, much less meeting the other partner to check on how this setup is sitting with him.

Demanding to know everything undermines intimacy, but so does demanding to know nothing. When we demand to know nothing, we cut ourselves off from a part of our partners' experience, and that must necessarily limit how intimate we can be.

The issue always seems to circle back to these questions: "How much do you trust your partners? How much do you trust your relationships? Do you trust your partners enough to allow intimacy, not limiting what you can hear? Do you trust your partners enough to leave them their private spaces, knowing that they will share things that are important and relevant to you so you can continue to make informed choices?"

DOUBLE STANDARDS

Rules that place different restrictions on different people are problematic in any situation, and polyamory is no exception. Double standards can be blatant and obvious: for example, Playboy founder Hugh Hefner is famous for having sexual relationships with multiple women simultaneously, all of whom are expected to have no lovers but him. But double standards can also be more subtle and sneaky. A common example is when a couple has a rule stating that they can interrupt each other's dates with other partners if a member of the couple needs attention, but their other partners are not allowed to interrupt the couple's dates with each other.

A double standard might not even be a hardship for the person agreeing to it. If someone genuinely does not want multiple partners, for instance, and is okay with his partner having other lovers, a rule that she can but he can't would not limit him. But it's still a double standard; the rules are still different for her than for him. (It also raises the question of why the rule exists. If she genuinely isn't interested in others, why was the rule imposed?)

Sometimes double standards are deliberately engineered to create different classes of people. If members of a couple claim the right to veto relationships with other people, but other partners are not given veto power over the couple's relationship, a deliberate double standard exists. The couple may see this double standard as a way to prevent new partners from "causing" them to break up.

Whenever rules apply unevenly to different people, there is potential for trouble, resentment and jealousy. (Ironically, double standards are often instituted as a way to prevent jealousy, at least within an established relationship, but far more often they end up creating it.) Rules that codify a double standard are disempowering. Be careful with rules that create double standards—both in setting them and, if you're starting a new relationship with someone who has them, in agreeing to them.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

When considering your needs for agreements or rules, or whether to sign on to someone else's, these questions can be useful.

- What needs am I trying to address with this agreement?

- Does the agreement offer a path to success?

- Does everyone affected by the agreement have the opportunity to be involved in setting its terms?

- How is the agreement negotiated, and under what circumstances can it be renegotiated?

- What happens if the agreement doesn't work for my partners, or my partners' partners?

- Do I feel like I need rules to feel safe? If so, will the rules actually keep me safe?

- Are my rules equally binding on everyone they affect, or do they create a double standard?

11

HIERARCHY AND PRIMARY/SECONDARY POLY

You must love in such a way that the person you love feels free.

THÍCH

NAHT

HANH

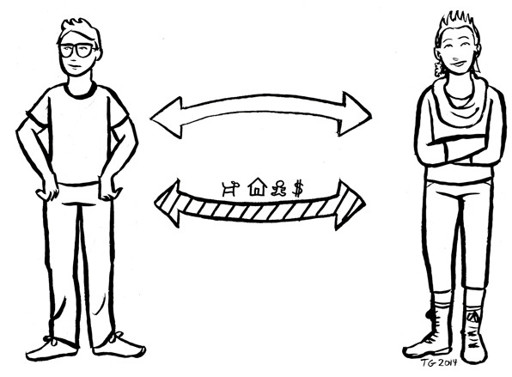

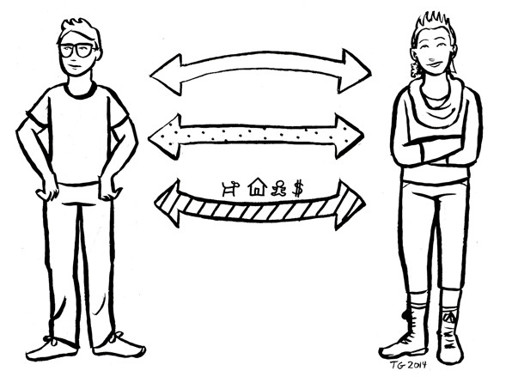

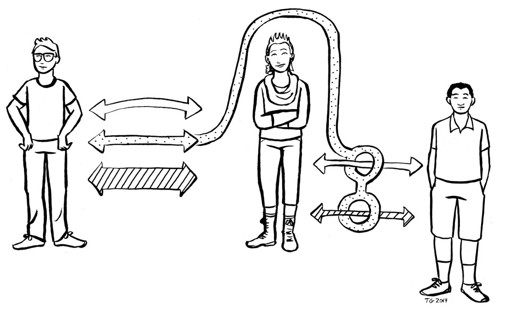

Whatever your position may be in a relationship network, polyamory brings risk. We have already talked about some of the ways people try to deal with these risks, not always wisely, and the strategies we recommend. Before we go further, we want to examine some of the underlying forces that shape any relationship. We're going to simplify—a lot—to construct a framework that lets us get our ideas across. The three main forces we will discuss here are

connection, commitment

and

power

.

HOW HIERARCHIES EMERGE

Connection

can mean a whole bunch of things, but here it represents what people see as the exciting bits of a relationship: intensity, passion, shared interests, sex, joy in each other's presence. It's the things that bring you together.

Commitment

consists of what you build in a relationship over time. It includes expectations: perhaps of continuity, reliability, shared time and communication, activities that will be done together, or a certain public image. Commitment often supports life responsibilities, such as shared finances, a home, or children.

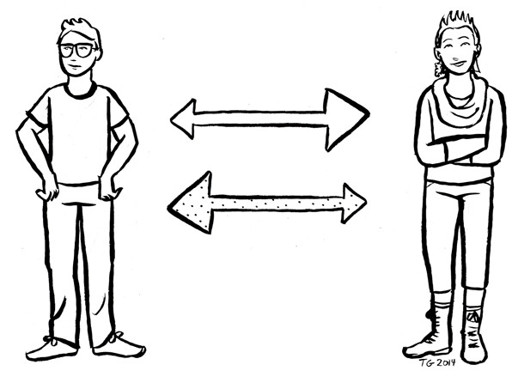

It's common for connection to start out very large and exciting and shrink as a relationship deepens and stabilizes, or sometimes to start out small, grow to a peak and then wane. Commitment tends to start small and grow. People in long-term, very committed relationships may still struggle to maintain connection.

Each of these flows—connection, commitment—gives people

power

in a relationship. Power tends to be proportional to the size of the other flows. The more we've committed to a relationship, and the more connection we feel with someone, the greater the power that person has—to affect not only ourselves and our relationship with that person, but all our other relationships as well.

Ideally, the power flows within intimate relationships would always be equal. In practice, they often are not. Power imbalances tend to arise when the other flows are asymmetrical: when one person feels more connection or commitment than the other. That's normal. The person who feels less connection or commitment tends to hold more power. Other things influence power dynamics too, of course: things like economic or social status, physical dominance or persuasion skills.

When someone is in a relationship with a large mutual commitment, especially when that commitment supports a lot of life responsibilities, it's common for a member of that relationship to feel threatened when a partner's new relationship has a really big connection—perhaps one that feels (and maybe really is) bigger than the existing connection.

Often, it's just the

idea

of a big connection that's scary, even when the flow is new and small. And the idea of a partner creating significant commitments to a new partner may feel (and sometimes is) threatening to the commitments that already exist.

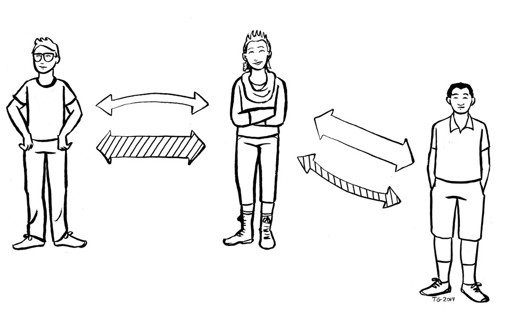

One way people deal with this fear is by using the power from within their own relationship to restrict the connection, commitment, or both in other relationships.

Such restrictions have a couple of defining features:

- Authority.

A person or people in one relationship, usually called the "primary" relationship, have the authority to restrict other relationships, often called "secondary." - Asymmetry.

The people within the secondary relationships do not have the same authority to limit the primary relationship.

When these two elements are present within a poly relationship, that relationship is hierarchical.

WHAT IS HIERARCHY?

Some people use the word

hierarchy

whenever one relationship has more commitments or responsibilities than another—for instance, members of a long-married couple with a house and kids becoming involved with a friend-with-benefits. This is

not

how we are using the word

hierarchy

in this book. When we talk here about a hierarchy, we mean a very specific

power dynamic:

where one relationship is subject to the control of someone outside that relationship. For instance, a hierarchy exists if a third party has the power to veto a relationship or limit the amount of time the people in it can spend together.

You can't throw a calendar in a group of poly people without hitting a hierarchical relationship. Hierarchical behavior might take the form of a rule that "No other partner may ever live with us," for example. Alternatively, it might manifest as restrictions on how strong another relationship is allowed to become, or on what a new person is allowed to do, where they are allowed to go, or what they are allowed to feel. Some common examples of prescriptions in hierarchical polyamory are: