Mind and Emotions (17 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

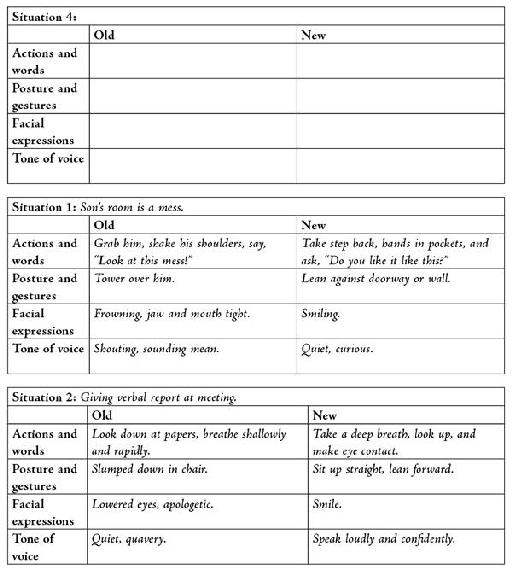

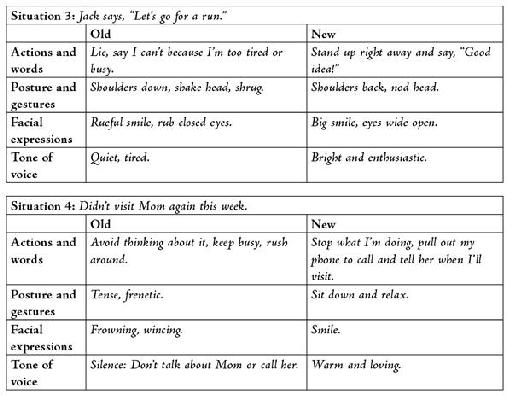

Doing the Opposite

Now for the hard part: actually doing the opposite. Pick the easiest, least threatening situation to start with, then commit to doing the opposite in a particular situation with a particular person. As the situation unfolds and you feel the familiar anxiety, sadness, or whatever, remember your plan. Take the actions you outlined and say what you intend to say, adopt the posture and use the gestures you planned, force your face into the intended expression, and be sure your tone of voice supports doing the opposite. Afterward, evaluate the experience with these questions in mind:

- How did you do? Be kind to yourself and realize that you won’t get it 100 percent right the first time.

- More importantly, how did you feel? Did your usual feelings decrease or change in any way? Did you experience any emotions that felt new in that situation?

- What did you learn that will help you do better next time? Incorporate these new ideas into your plan.

Use the last question to improve and fine-tune your plan for the next time you find yourself in that situation. If you struggle with doing the opposite, here are some tips that may help:

- Select an easier person or situation to start with.

- Create reminders so you won’t forget to follow through on your commitment.

- Share your plan and your commitment to it with someone who cares about you.

- Do part but not all of what you planned, and then gradually do more.

Work your way through all of the situations you explored, from least to most difficult. In each case, do the opposite, evaluate your results, and revise your plan for that situation accordingly. Continue until you’ve done the opposite successfully in all of the problem situations you described. At that point, you’ll have enough practice to begin incorporating this skill into your day-to-day life. You may want to continue to analyze your old responses and draw up plans for doing the opposite, or you may find that this skill starts to come to you more naturally.

Finding Motivation

If you’re having trouble putting this chapter into practice, consider the threefold benefits of doing the opposite. First, pushing through your painful feelings to do the opposite of your usual emotion-driven behaviors will let you in on a valuable secret about difficult feelings: They are neither permanent nor fatal. All feelings, including anxiety, sadness, fear, anger, and guilt, arise, come to a peak, and then subside and go away, leaving you calmer and more functional on the other side. Second, acting contrary to your feelings will give you a sense of empowerment—a sense that you’re more in control. And third, it will allow you to participate more fully in your life, living according to your values rather than your fears and doubts.

To highlight the benefits of doing the opposite for you personally, consider each of the situations you worked with in this chapter and make a list of the benefits you hope to gain. You might want to make several copies of the blank worksheet so you can use it for multiple situations, or you can just list the benefits on a separate piece of paper.

Benefits of Doing the Opposite

Relationship with your spouse or partner: _______________

_______________

Relationship with friends and family: _______________

_______________

Work or school: _______________

_______________

Financial: _______________

_______________

Living situation: _______________

_______________

More time, energy, or opportunity for: _______________

_______________

Safety and security: _______________

_______________

Long-term goals: _______________

_______________

If you haven’t already started working on doing the opposite, now is the time to make a written commitment to do so. Pick the least threatening situation on your list and write down precisely when, where, and with whom you will first do the opposite. Then follow through on your commitment.

When I’ll do it: _______________

Where I’ll do it: _______________

With whom I’ll do it _______________

Applications

Doing the opposite when you feel anxious is a matter of turning toward and approaching whatever you would normally turn away from and avoid. For example, during the lunch hour at a conference, instead of slipping away on your own to eat a quiet, solitary lunch, you’d accept your coworkers’ invitation to go to a restaurant and, once there, you’d actively engage in the conversation.

If you’re depressed and would normally throw the day’s mail on the dining room table, where it accumulates for weeks, instead do the opposite: Open the mail right away, sort it, pay the bills, throw out the junk, and so on. Keep up with the mail daily and keep the dining room table clear of everything but fresh flowers.

For anger, doing the opposite involves changing your usual gestures, tone of voice, and how quickly you respond to provocation. If you’d normally respond to your father’s political opinions with sarcastic interruptions, escalating to loud name-calling and pounding on the table, instead listen respectfully until your father finishes a sentence. Then keep your hands in your lap and ask a neutral question in a normal tone of voice, for example, “That’s an interesting way of looking at it. How did you arrive at that conclusion?”

If you feel ashamed and guilty you might enter a family reunion with your head down and shoulders slumped, and then slip into a seat in the corner without making eye contact or saying hello to the others in the room. To do the opposite, walk briskly into the room with your head and shoulders up, stride over to your aunt, greet her enthusiastically, and give her a big hug.

Duration

It will take two to six months to make a habit of doing the opposite. As you practice this powerful technique, you’ll have surprising successes, occasional setbacks, and periods when you seem to plateau and nothing changes for a while. But over time, you will form new habits of reacting to old painful feelings that lessen those feelings and help make them more short-lived.

Eventually, difficult feelings will become a signal to automatically employ opposite action. You’ll react almost unconsciously, accepting previously overwhelming emotions and allowing them to arise, subside, and flow through you without disrupting your life or controlling your behavior.

Chapter 10

Interpersonal Effectiveness

What Is It?

Many painful emotions come up when dealing with other people, especially if you don’t use good communication skills. This chapter teaches the basic communication skills you need to improve your relationships with your partner, family, and friends. When you can hear and understand other people’s desires and feelings and communicate your own clearly and assertively, dealing with other people becomes easier and you feel less anxiety, depression, anger, shame, and guilt.

Improving interpersonal effectiveness skills is a key component of dialectical behavior therapy, and researchers have found that teaching interpersonal effectiveness skills is an important part of treating emotional disorders (Linehan 1993).

Why Do It?

Interpersonal effectiveness leads to healthy, meaningful, and long-lasting relationships. The skills you’ll learn in this chapter will help you feel less overwhelmed by emotions such as anger, guilt, fear of rejection, or sadness about relationships that aren’t working.

Interpersonal effectiveness directly targets two transdiagnostic factors: hostility or aggression and response persistence. When you can recognize your feelings, express your needs, and set reasonable limits, you’re likely to find yourself in far fewer situations where you’re inclined to respond with anger. And because increased interpersonal effectiveness will give you new and better ways to communicate and interact with others, you won’t be as likely to respond to difficult people and interactions in the old, ineffective ways.

What to Do

In this chapter, you’ll learn some interpersonal effectiveness skills that will help you cope with difficult emotions—and help prevent problematic situations from arising in the first place: listening to and really hearing others, figuring out what you want and how to express your feelings and needs, and dealing with conflicts assertively rather than passively or aggressively. First we’ll discuss the various skills and help you understand how to use them, then we’ll offer some tips on how to practice them before implementing them in real-life situations.

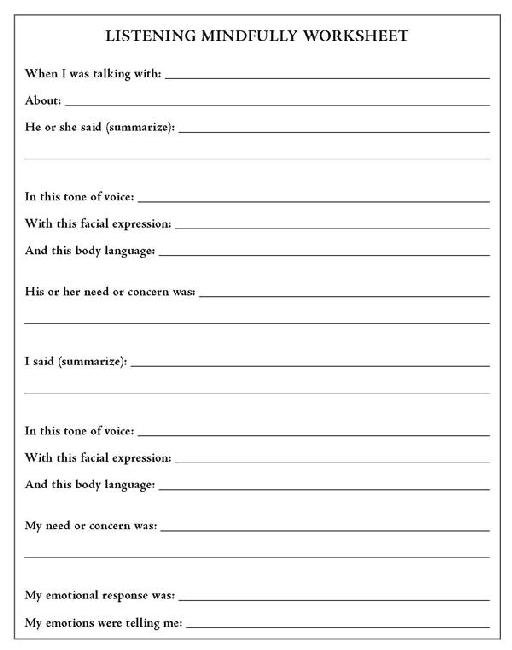

Listening Mindfully

In conversations with others, how often do you daydream or prepare your response while the other person is talking to you? Like many people, you may do this quite often, but if you do, you run the risk of missing important parts of the conversation. Not listening closely is a kind of interpersonal blindness that can lead to misunderstanding and confusion.

When you listen mindfully, you apply the skills you learned in chapter 5, Mindfulness and Emotion Awareness, to your conversations, noticing the full details of a conversation, including the verbal content, your emotional reaction, and nonverbal cues such as tone of voice, gestures, facial expressions, and body language.

While you could just set an intention to listen more mindfully, you may find it helpful to practice increasing the scope of your observations by reviewing a recent conversation. This exercise will help you get a better idea of the types of information you need to tune in to, beyond the verbal content. We recommend that you do this exercise for several conversations, so make a few copies and leave the version in the book blank for future use.

How did you do? Did you have to leave some parts blank because you hadn’t noticed a lot of the emotional and nonverbal parts of the conversation? Try analyzing another recent conversation and see if you can detect a pattern in the information you tend to overlook. Do you miss the nonverbal cues, or are you unclear about the underlying needs or emotions of others or yourself?

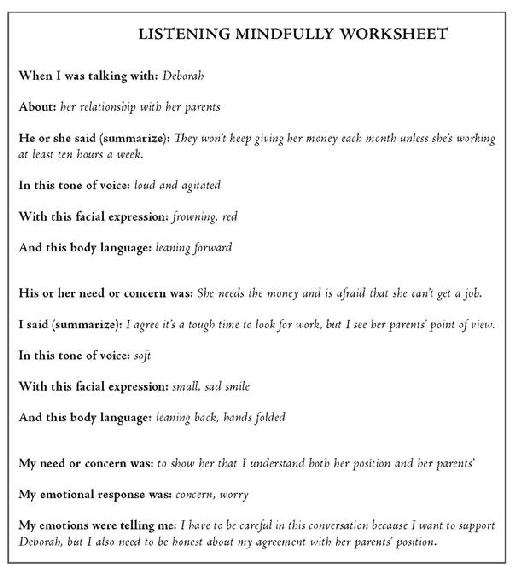

By now it should be obvious that listening mindfully is not a simple task. The next time you have a conversation with someone, pay close attention to all the items covered on the worksheet and then carefully analyze the interaction later. Here is an example of how Diego analyzed his conversation with Deborah, after he had been working on mindful listening for a couple of weeks.