Mind and Emotions (13 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

Understanding the Purpose of Negative Focus

As we’ve said, all behavior, even thought, has a function. Focusing on the negative usually has one of these four functions:

- Discharging negative affect that has built up in painful situations

- Reducing expectations and disappointments

- Avoiding future negative experiences

- Trying to perfect oneself or get rid of flaws through negative self-evaluation

Think about some of the negative thoughts you return to again and again. Which of the above four functions might apply? You may discover functions for these thoughts other than those we listed; that’s fine too.

Now, for the key question: Are these negative thoughts doing what they’re supposed to do? Are they discharging pain, reducing disappointment, helping you avoid future pain, or making you a better person? If so, fine. But if not, they aren’t working. The fact is, most people don’t derive much benefit from a negative focus. They feel more pain, not less, and more disappointment because they spend so much time remembering things that went wrong. Paradoxically, they don’t seem able to avoid painful events, but this is actually a function of their focus: negative events are all they pay attention to, so they tend to miss positive experiences. And self-critical thoughts usually have the effect of making people feel more flawed, not less.

So when you catch yourself in a negative focus, ask yourself, “Is this working? Does this help me in any way?” If the answer is no, acknowledge the thought and label it, saying something like “There’s one of my ‘life’s no good’ thoughts.” Then let it go. Of course, it will show up again, but just keep labeling these thoughts and letting them go. Eventually they’ll seem less important and less convincing.

Cognitive Flexibility with Negative Attributions

We humans like to find out why things happen, because if you can explain events you can often control or anticipate them. The trouble is, an event or behavior can often be explained in different ways. This is particularly true of ambiguous behavior, like someone frowning, shrugging, or moving a little distance away. You can’t help trying to interpret such events, even though it’s impossible to know for sure what they mean. And if you have a negative bias, you’ll often interpret ambiguous behavior as a sign of rejection or displeasure.

The need to explain things is especially evident when something really bad happens: Your job is eliminated, you develop a serious illness, or someone you love withdraws. In such cases, a negative bias almost always leaves you at fault. You attribute these events to your own shortcomings or something you did wrong.

When the mind grabs onto explanations, it often won’t let go. Once you have an interpretation of why something happened, you tend to believe it and stick with it. The exercises in this section will help you be a little less absolute about negative attributions. They’ll help you discover multiple plausible explanations for the same event so that you’re less likely to cling to negative attributions with a sense that they must be true.

Finding Alternative Explanations

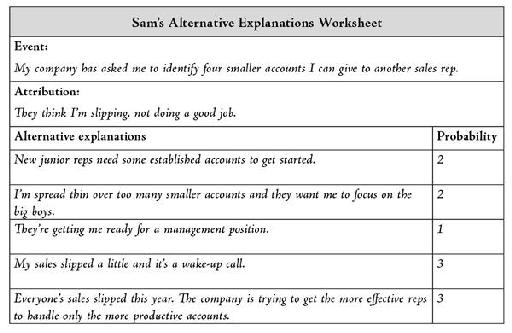

Whenever you answer the question

why

with a negative attribution, blaming yourself or someone’s negative feelings about you for the event, fill out the following Alternative Explanations Worksheet. (Make several copies and leave the version in the book blank for future use.) Describe the event briefly, along with your negative attribution as to its cause. Then brainstorm five to ten other possible explanations. For example, someone frowning could mean that the person was tired, bored, thinking of something to say, having an unpleasant memory, noticing physical pain, wanting to go home, worrying about something, and so on. If it seems helpful, you can rate the probability of each alternative using a scale of 1 to 3 in which 1 means slightly possible, 2 means somewhat likely, and 3 means likely. A sample worksheet follows the blank version.

It’s important to develop alternative explanations every time you have a negative attribution because it helps the attribution seem a little less absolute. Once you’re a bit less convinced of an attribution, your thinking becomes more flexible and you can see the same event from a number of vantage points.

Exploring Concurrent Realities

Sometimes it’s helpful to find out what other people think. Maybe they see the same event through a very different lens. When you find yourself seriously caught up in a negative attribution, find other people who witnessed the same event and ask them how they assessed the ambiguous frown, the layoff, the strange remark, or the sudden withdrawal. If you can’t find someone who witnessed the event, pick a sympathetic friend, describe what happened, and ask how your friend would explain the event. If the event hinges on another person’s behavior, you might even consider asking that person why he or she behaved that way. Once you’ve gathered one or two opinions from others, add them to your Alternative Explanations Worksheet for that event and rate their probability.

Here’s an example of how it works: When Sam told another sales rep about having his accounts reassigned, he was surprised to learn that his colleague had experienced the same thing. His colleague thought it was because small accounts were taking too much time and not earning much, and maybe the company didn’t want to service them anymore. Sam thought this seemed somewhat likely, so he added it to his list of alternative explanations and rated it a 2.

Cognitive Flexibility with Shoulds

It’s important to have values: guiding principles that help you live your life in a way that’s meaningful to you. However, values must always be understood in context. Sometimes the value of being open and truthful may have to play second fiddle to the value of being loving if truthfulness would do unnecessary damage in a particular situation. So it’s important to act on your values flexibly, depending upon the needs and circumstances of everyone involved.

Shoulds and rules are often too inflexible. Shoulds insist that you and others always act a certain way, no matter what, and rule-bound behavior can get you in trouble because it often brings you into conflict with other people’s rules or needs. Since rules and shoulds tend to be absolute—thought of as applying to everyone at all times—we often label ourselves or others as bad or wrong when rules are broken and shoulds are violated. This results in a lot of anger, guilt, shame, and depression.

To soften shoulds and rules and make them more flexible, you can do two things: express shoulds as preferences, not absolute rules; and broaden your understanding of why people break rules.

Transforming Shoulds into Preferences

Sometimes simply phrasing things differently can be a powerful way to increase cognitive flexibility, and this is definitely the case with shoulds. Whenever you’re inclined to use the words “should,” “ought to,” or “must,” try using the word “prefer” instead. Here are some examples:

- “You should work harder” becomes “I would prefer that you work harder.”

- “I should never show fear” becomes “I would prefer not to show fear.”

- “I must look confident” becomes “I would prefer to look confident.”

- “You should never be late” becomes “I’d prefer you not be late.”

Notice that “prefer” softens the absolute quality of shoulds and transforms them into an expression of what you personally desire. Start working on establishing this habit right now. Every time the word “should” pops up in your vocabulary, take note of it and immediately restate the sentence as a preference.

Understanding Reasons for Breaking the Rules

Why do people sometimes behave in ways that violate cherished beliefs about how we should act? Why do things happen that shouldn’t? The answer is largely cause and effect. Long chains of events lead people to see the world in a certain way, need certain things, fear certain outcomes, know or not know how to do certain things, resist or dislike certain things, and so on. When you add all of that up (if you actually could), it accounts for most behavior. People do what they do not because it’s what they should do, but because of long strands of cause and effect, often originating in their deep past. It might be useful to move beyond the idea that people

should

do anything. We all do what we do because of a matrix of complex causes.

The Breaking the Rules Worksheet that follows will help you identify people’s reasons for breaking the rules—whether the person is you or someone else. (Make several copies and leave the version in the book blank for future use.) Start by briefly describing a recent situation where you or someone else broke a rule or violated a should. Next, briefly describe the rule that was violated. Then, under “Influencing Factors,” list your speculations about how each factor might have influenced what happened. Each time you fill out this worksheet, you’ll gain insight into how choices get made—and perhaps find more acceptance or forgiveness for those times when people, yourself included, break the rules. A sample worksheet follows the blank version.

Breaking the Rules Worksheet

Situation:

_______________

_______________

Rule that was violated:

_______________

_______________

Influencing Factors

Fears:

_______________

_______________

Other emotions triggered:

_______________

Needs:

_______________

_______________

Pain or pleasure triggered by the situation:

_______________

_______________

History

(old experiences that might influence a response): _______________

_______________

Beliefs, values, and attitudes:

_______________

_______________

The behavior of others:

_______________

_______________

It’s okay to guess about influencing factors. The point isn’t to be right; it’s to recognize possible drivers for the behavior. Behavior isn’t just a matter of being good or bad, or right or wrong. It’s pushed and prodded by a lot of factors. Learning what some of them are is the key to developing cognitive flexibility around shoulds.

Laura filled out several Breaking the Rules Worksheets before she started to think more flexibly about why people don’t do what they should. This one was triggered by an evening when her mother got angry at her.

Laura’s Breaking the Rules Worksheet

Situation:

Mom got mad at me for “always complaining” when I said I don’t like cheese on breaded veal.

Rule that was violated:

People shouldn’t get angry; they should be polite.

Influencing Factors

Fears:

Mom is afraid of disapproval.

Other emotions triggered:

I think she was embarrassed.

Needs:

Mom needs to feel like she’s pleasing and taking care of everybody. She feels like she screwed up if I don’t like something she does.

Pain or pleasure triggered by the situation:

I took away her pleasure in making us a nice meal.

History

(old experiences that might influence a response):

Mom’s mother was the self-sacrificing type. Everything was about doing for others.

Beliefs, values, and attitudes:

She thinks her main job in life is to make everyone happy; I guess I made her feel she was failing at it.

The behavior of others:

I think what I said sounded sharp and disapproving.