Mark Griffin (53 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

While furthering the nostalgia craze that swept through the ’70s,

That’s Entertainment!

also revived interest in Minnelli’s movies, which were suddenly in demand in art houses and on college campuses. It was around this time that cults formed around some of Vincente’s more esoteric efforts, especially

The Pirate

and

Yolanda and the Thief

. In the psychedelic ’70s, Minnelli’s Technicolor fantasylands and surrealistic dream sequences suddenly found a very receptive—if heavy-lidded—audience.

That’s Entertainment!

also revived interest in Minnelli’s movies, which were suddenly in demand in art houses and on college campuses. It was around this time that cults formed around some of Vincente’s more esoteric efforts, especially

The Pirate

and

Yolanda and the Thief

. In the psychedelic ’70s, Minnelli’s Technicolor fantasylands and surrealistic dream sequences suddenly found a very receptive—if heavy-lidded—audience.

In 1975, writer and documentarian Richard Schickel interviewed Minnelli on camera for his acclaimed eight-part television series

The Men Who Made the Movies

, which profiled master directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. “I stayed in touch with Vincente a little bit after

The Men Who Made the Movies

,” says Schickel. “He was a very kindly gentleman. He was kind of inarticulate—stammering and so forth. And sort of hidden in certain ways. You know, he wrote that autobiography

I Remember It Well

and I always laugh when I look at that title on the shelf because he didn’t remember anything. But he was a fabulous filmmaker. You know, as the years go on and you look at Vincente’s contributions, he seems to loom larger in film history than maybe he seemed to at the time.”

14

The Men Who Made the Movies

, which profiled master directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks. “I stayed in touch with Vincente a little bit after

The Men Who Made the Movies

,” says Schickel. “He was a very kindly gentleman. He was kind of inarticulate—stammering and so forth. And sort of hidden in certain ways. You know, he wrote that autobiography

I Remember It Well

and I always laugh when I look at that title on the shelf because he didn’t remember anything. But he was a fabulous filmmaker. You know, as the years go on and you look at Vincente’s contributions, he seems to loom larger in film history than maybe he seemed to at the time.”

14

37

A Matter of Time

FOR YEARS, VINCENTE AND LIZA had searched for the perfect project on which to collaborate. At one point, the Minnellis thought they had found an ideal vehicle in Nancy Milford’s acclaimed 1970 biography of Jazz Age icon Zelda Fitzgerald. Milford’s recounting of the life of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s free-spirited though deeply troubled wife seemed like natural biopic material. Although Paramount initially expressed interest, this

Zelda with a “Z”

was not to be. Undaunted, Vincente turned his attention to a story that had long fascinated him. “When I first read the English translation of Maurice Druon’s

Film of Memory

, I felt it would make a marvelous picture,” Vincente recalled. “The book had been optioned by several film producers over the years. Whenever I got my offer in, it was either too little or too late. I had given up hope that I’d ever be involved with that lovely story.”

1

Zelda with a “Z”

was not to be. Undaunted, Vincente turned his attention to a story that had long fascinated him. “When I first read the English translation of Maurice Druon’s

Film of Memory

, I felt it would make a marvelous picture,” Vincente recalled. “The book had been optioned by several film producers over the years. Whenever I got my offer in, it was either too little or too late. I had given up hope that I’d ever be involved with that lovely story.”

1

Published in 1955, Maurice Druon’s novel

The Film of Memory

seemed ready-made for Minnelli.

az

The story concerned Carmela, a timid, impressionable chambermaid living vicariously through the memories of the half-mad Contessa Sanziani, a resident in the dilapidated hotel where Carmela works. The old Renaissance queen’s recollections of her glamorous past as a coveted European courtesan inspire Carmela to fantasize about an exotic existence beyond her mindless routine of changing bed sheets.

The Film of Memory

seemed ready-made for Minnelli.

az

The story concerned Carmela, a timid, impressionable chambermaid living vicariously through the memories of the half-mad Contessa Sanziani, a resident in the dilapidated hotel where Carmela works. The old Renaissance queen’s recollections of her glamorous past as a coveted European courtesan inspire Carmela to fantasize about an exotic existence beyond her mindless routine of changing bed sheets.

Teetering on the edge of insanity, the contessa tutors the unworldly fifth-floor maid in the fine art of living. As La Sanziani retreats further into her

hallucinatory film of memory, she is more than a few frames out of synch with the world around her, and her decline seemed to eerily mirror Vincente’s fading status in the film industry. In an era dominated by the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese, the seventy-two-year-old Minnelli was seen as an out-of-touch, fusty relic and one totally dependent on his daughter’s star power to secure financing for any new endeavors. Friends recalled that after

On a Clear Day

, Vincente seemed perfectly content ensconced in his Crescent Drive sanctuary, lounging in an elegant silk robe and painting. Why should he have to trouble himself with mounting another elaborate film production when most of his colleagues were enjoying a quiet retirement?

hallucinatory film of memory, she is more than a few frames out of synch with the world around her, and her decline seemed to eerily mirror Vincente’s fading status in the film industry. In an era dominated by the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese, the seventy-two-year-old Minnelli was seen as an out-of-touch, fusty relic and one totally dependent on his daughter’s star power to secure financing for any new endeavors. Friends recalled that after

On a Clear Day

, Vincente seemed perfectly content ensconced in his Crescent Drive sanctuary, lounging in an elegant silk robe and painting. Why should he have to trouble himself with mounting another elaborate film production when most of his colleagues were enjoying a quiet retirement?

“I think he did it because of Liza,” says screenwriter John Gay, who was tasked with transferring Druon’s psychologically layered prose to film. “[Vincente] looked at it as a project to star his daughter and they always wanted to work together. They really were devoted to each other.” Naturally, Liza would be playing Carmela

ba

—though an eternally sequined, Studio 54 habitué seemed more suitably cast as the hedonistic Sally Bowles in

Cabaret

than a mousy maid from the provinces. “I have to tell you I was a little bit surprised,” Gay says of casting Liza, the glittering showstopper, as a shrinking violet. “I mean, I know why he wanted his daughter for it but Liza is like you see her on the screen. I mean, she’s just

all over

. I thought the personality of Liza would be a little bit over the top, shall we say, and she’d have to hold it down to play the maid.”

2

ba

—though an eternally sequined, Studio 54 habitué seemed more suitably cast as the hedonistic Sally Bowles in

Cabaret

than a mousy maid from the provinces. “I have to tell you I was a little bit surprised,” Gay says of casting Liza, the glittering showstopper, as a shrinking violet. “I mean, I know why he wanted his daughter for it but Liza is like you see her on the screen. I mean, she’s just

all over

. I thought the personality of Liza would be a little bit over the top, shall we say, and she’d have to hold it down to play the maid.”

2

Even with a red hot, post-

Cabaret

Liza on board, a character-driven drama about a dreamy chambermaid and a senile countess didn’t seem destined for box-office glory. As

Carmela

would be competing against the likes of

Mother, Jugs and Speed

, and

Corvette Summer

, the story the Minnellis were pitching seemed almost hopelessly quaint—about as up-to-the-minute as the Victrola. From a marketing standpoint, there was no sizzling romance to exploit, at least not one of the traditional Streisand-Redford variety.

Cabaret

Liza on board, a character-driven drama about a dreamy chambermaid and a senile countess didn’t seem destined for box-office glory. As

Carmela

would be competing against the likes of

Mother, Jugs and Speed

, and

Corvette Summer

, the story the Minnellis were pitching seemed almost hopelessly quaint—about as up-to-the-minute as the Victrola. From a marketing standpoint, there was no sizzling romance to exploit, at least not one of the traditional Streisand-Redford variety.

“Actually, the thing was a love story between the chambermaid and the countess, if you want took at it that way. That’s really what it was all about,” says Gay.

3

But who would finance such a commercially risky venture? The major studios, including MGM (which for a time had optioned the property) took turns turning down the Minnellis. “I found myself, in a way, auditioning the project before the money men,” Vincente recalled. It was a humiliating experience. Despite his legendary Oscar-winning track record, the elder

Minnelli wasn’t received with open arms by junior executives in search of the next big roller-boogie cash cow.

3

But who would finance such a commercially risky venture? The major studios, including MGM (which for a time had optioned the property) took turns turning down the Minnellis. “I found myself, in a way, auditioning the project before the money men,” Vincente recalled. It was a humiliating experience. Despite his legendary Oscar-winning track record, the elder

Minnelli wasn’t received with open arms by junior executives in search of the next big roller-boogie cash cow.

Then came a glimmer of hope from a most unlikely source. Samuel Z. Arkoff’s American International Pictures was famous for such four-star schlock as

The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini

and

Attack of the Puppet People

. AIP, which had launched the careers of Jack Nicholson and “King of the B’s” director Roger Corman, expressed interest in cofinancing Vincente Minnelli’s long-awaited return. In taking on

Carmela

(as the project was then titled), Arkoff would be acquiring two Oscar-winning Minnellis at bargain-basement prices, plus a prestige project that might single-handedly obliterate the memory of such dubious Arkoff enterprises as

I Was a Teenage Werewolf

and

Girls In Prison

. A Vincente Minnelli movie was AIP’s opportunity to finally go legit.

The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini

and

Attack of the Puppet People

. AIP, which had launched the careers of Jack Nicholson and “King of the B’s” director Roger Corman, expressed interest in cofinancing Vincente Minnelli’s long-awaited return. In taking on

Carmela

(as the project was then titled), Arkoff would be acquiring two Oscar-winning Minnellis at bargain-basement prices, plus a prestige project that might single-handedly obliterate the memory of such dubious Arkoff enterprises as

I Was a Teenage Werewolf

and

Girls In Prison

. A Vincente Minnelli movie was AIP’s opportunity to finally go legit.

John Gay attempted to warn the film’s leading lady about the type of fly-by-night producers they now found themselves in bed with. “I said to Liza, ‘These guys are very tough. I mean, Vincente better watch out.’ She said, ‘Are you kidding? Daddy may look flighty but he’s hard as nails. He can handle any of these guys.’ But Vincente was weaker at that time. He was getting older. I don’t think that Vincente had the old stamina that Liza said he always had.”

4

4

Arkoff was being cautioned as well. As the producer recalled, “A couple of my friends in Hollywood warned me, ‘[Minnelli] hasn’t done a picture in a number of years. Be careful what you’re getting yourself into. When he was making the big musicals, MGM surrounded him with the best cameramen and best set designers. All of them knew what the pictures needed without even asking him.’”

5

5

With both factions forewarned, the producers turned their attention to the crucial casting of the secondary lead. Two-time Oscar-winner Luise Rainer and Italian leading lady Valentina Cortesa were both considered for the pivotal role of the grandest dowager of them all, the Contessa Sanziani. AIP and its Italian cofinancier, however, insisted on an actress with more potent box-office allure, and they got exactly that in the form of the incandescent Ingrid Bergman, who had recently won her third Oscar for her supporting role in

Murder on the Orient Express

. Although Bergman readily accepted the challenging role, she was quick to point out that she was nothing like her character: “She is just the opposite of myself, because she is destroying herself by dreams of her youth. I don’t dream about my past. I accept my age [sixty] and make the best of it.”

6

Murder on the Orient Express

. Although Bergman readily accepted the challenging role, she was quick to point out that she was nothing like her character: “She is just the opposite of myself, because she is destroying herself by dreams of her youth. I don’t dream about my past. I accept my age [sixty] and make the best of it.”

6

Cast as Lucrezia Sanziani’s former husband was Minnelli favorite Charles Boyer, who had appeared opposite Bergman in

Gaslight

and

Arch of Triumph

. With such a high-profile cast assembled, it seemed as though everything had

finally fallen into place for Minnelli. Nevertheless, once shooting began—on location in Rome—it wasn’t long before word leaked out that the production was floundering; the director known for his attention to the most microscopic details was said to be having inordinate difficulty focusing. Present on the set to interview Liza, writer Clive Hirschhorn observed that Vincente was no longer in full command. “He was really doddery and old and he was shouting ‘

Action

!’ when he meant to say, ‘Cut!’ and vice-versa,” Hirschhorn says. “It was a very sad occasion. No one seemed to know what they were doing.”

7

Gaslight

and

Arch of Triumph

. With such a high-profile cast assembled, it seemed as though everything had

finally fallen into place for Minnelli. Nevertheless, once shooting began—on location in Rome—it wasn’t long before word leaked out that the production was floundering; the director known for his attention to the most microscopic details was said to be having inordinate difficulty focusing. Present on the set to interview Liza, writer Clive Hirschhorn observed that Vincente was no longer in full command. “He was really doddery and old and he was shouting ‘

Action

!’ when he meant to say, ‘Cut!’ and vice-versa,” Hirschhorn says. “It was a very sad occasion. No one seemed to know what they were doing.”

7

Tongue-tied and unintelligible even under the best of circumstances, Vincente found himself at a loss for words on the set. To make matters worse, he was attempting to address a largely non-English speaking crew. Pacing—never Vincente’s strong suit—was another challenge. “Almost immediately, . . . the production fell behind schedule,” Arkoff remembered. “When I was on the set, Vincente would talk endlessly about the sets and costumes, but he just couldn’t seem to pull the picture together. . . . I tried to talk to him a few times—‘Vincente, I think you need to take stronger control of the picture. These actors need more guidance from you.’”

8

8

But the rigors of shooting a major production in a foreign location were proving to be too much for Minnelli, who was grappling with challenges far greater than the movie. “We didn’t realize it yet, but Vincente was already in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” Liza’s half sister, Lorna Luft, would recall in her memoir:

There wasn’t much knowledge of Alzheimer’s at the time, and we didn’t understand why Vincente was acting so strangely. We kept trying to laugh it off when he made odd mistakes. One day he came into the dressing room and called Liza “

Yolanda

.” . . . We comforted ourselves with the notion that he was getting older, and that he hadn’t directed a movie in many years. It was tragic to watch the brilliant man who’d directed

An American in Paris

struggling just to function.

9

Yolanda

.” . . . We comforted ourselves with the notion that he was getting older, and that he hadn’t directed a movie in many years. It was tragic to watch the brilliant man who’d directed

An American in Paris

struggling just to function.

9

By all accounts, Liza offered Vincente unwavering support throughout the production, though even she felt the need to turn to others for guidance, including screenwriter John Gay. “There was one scene where the contessa is by the window,” Gay recalls:

[Liza and Ingrid] had this scene together and the Contessa talks about the birds. And just before that scene, Liza said to me, “Oh, I’m so worried about this scene. Would you please watch it to see how I do?” So, I did. I watched

the scene and I was so elevated by Bergman. She was so absolutely wonderful in that scene. When it was over, I rushed over to Bergman and I said, “That was wonderful . . .” and I turned to Liza and I realized I should have gone to her first. She asked me to watch the scene. She was nervous about the scene. Oh, that was a real faux pas.

10

the scene and I was so elevated by Bergman. She was so absolutely wonderful in that scene. When it was over, I rushed over to Bergman and I said, “That was wonderful . . .” and I turned to Liza and I realized I should have gone to her first. She asked me to watch the scene. She was nervous about the scene. Oh, that was a real faux pas.

10

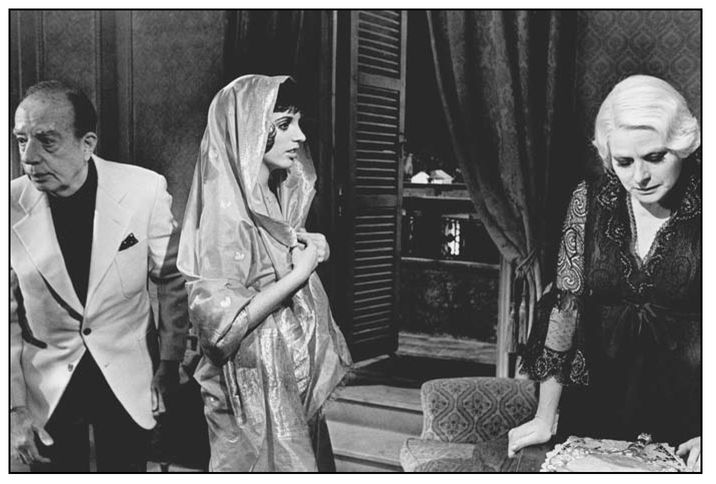

The Minnellis and Ingrid Bergman on the set of

A Matter of Time

. Vincente’s final film was mutilated by American International Pictures, motivating director Martin Scorsese to publish a protest in Hollywood trade papers signed by over thirty directors. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

A Matter of Time

. Vincente’s final film was mutilated by American International Pictures, motivating director Martin Scorsese to publish a protest in Hollywood trade papers signed by over thirty directors. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

While production wrapped on March 13, 1976, Vincente’s real battles were only beginning. The rough cut of the picture, now retitled

A Matter of Time

, seemed unusually long even by Minnelli standards. The psychological subtleties and emotional nuances of the story were apparently lost on Arkoff, who found Vincente’s initial assembly incoherent and interminable. When asked to outline his intentions, Minnelli had difficulty verbalizing his overall vision of the film. Frustrated and impatient, the producer announced that he would supervise a drastic re-edit. After Vincente and Liza pleaded with Arkoff for an opportunity to rework the footage, the producer relented, but he would only allow Vincente to use the footage from his initial assembly—nothing more. Arkoff deemed Minnelli’s second attempt unsatisfactory as well and sharpened his scissors.

A Matter of Time

, seemed unusually long even by Minnelli standards. The psychological subtleties and emotional nuances of the story were apparently lost on Arkoff, who found Vincente’s initial assembly incoherent and interminable. When asked to outline his intentions, Minnelli had difficulty verbalizing his overall vision of the film. Frustrated and impatient, the producer announced that he would supervise a drastic re-edit. After Vincente and Liza pleaded with Arkoff for an opportunity to rework the footage, the producer relented, but he would only allow Vincente to use the footage from his initial assembly—nothing more. Arkoff deemed Minnelli’s second attempt unsatisfactory as well and sharpened his scissors.

Vincente had endured studio tampering with his work before.

The Pirate

,

The Cobweb

,

Two Weeks in Another Town

, and

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever

had all fallen prey to the editor’s sheers, but nothing could have prepared Minnelli for the ensuing massacre. Arkoff gutted the picture. Scenes in which “Sanziani dragged the little maid across Europe on a tour of hallucination” (as Maurice Druon had put it) were mercilessly pruned.

11

Virtually all of Edmund Purdom’s scenes were axed. Anna Proclemer’s role as the contessa’s faithful confidante, Jeanne Blasto, was hacked out entirely, though references to her character remain in the release print.

The Pirate

,

The Cobweb

,

Two Weeks in Another Town

, and

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever

had all fallen prey to the editor’s sheers, but nothing could have prepared Minnelli for the ensuing massacre. Arkoff gutted the picture. Scenes in which “Sanziani dragged the little maid across Europe on a tour of hallucination” (as Maurice Druon had put it) were mercilessly pruned.

11

Virtually all of Edmund Purdom’s scenes were axed. Anna Proclemer’s role as the contessa’s faithful confidante, Jeanne Blasto, was hacked out entirely, though references to her character remain in the release print.

Other books

Justice Done by Jan Burke

King of the Bastards by Brian Keene, Steven L. Shrewsbury

The Ties That Bind by T. Starnes

Koko by Peter Straub

Hired: The Italian's Bride by Donna Alward

The Gemini Virus by Mara, Wil

La velocidad de la oscuridad by Elizabeth Moon

Paying The Piper by Simon Wood

Crash & Burn by Lisa Gardner