Mark Griffin (48 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

AFTER THE FULL-BLOWN CATASTROPHE that was

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

, it seemed like some sort of demented kamikaze mission for MGM to reunite the apocalyptic trio of Minnelli, Glenn Ford, and screenwriter John Gay for

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

. Only this time, the forecast was far sunnier.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

, it seemed like some sort of demented kamikaze mission for MGM to reunite the apocalyptic trio of Minnelli, Glenn Ford, and screenwriter John Gay for

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

. Only this time, the forecast was far sunnier.

Whereas

The Four Horsemen

had been overpopulated and epically scaled,

Eddie’s Father

was an intimate comedy. The characters were the kind of up-scale Manhattanites that captured Vincente’s imagination in ways that

Horsemen

’s underground radicals and resistance fighters had failed to. Also, for the first time, Minnelli was teamed with Joe Pasternak, a producer known for whipping up innocuous crowd-pleasers (

Nancy Goes to Rio

,

Skirts Ahoy!

) that always came in on time and under budget. If an Arthur Freed film was vintage champagne, a Pasternak production was more like strawberry milk.

The Four Horsemen

had been overpopulated and epically scaled,

Eddie’s Father

was an intimate comedy. The characters were the kind of up-scale Manhattanites that captured Vincente’s imagination in ways that

Horsemen

’s underground radicals and resistance fighters had failed to. Also, for the first time, Minnelli was teamed with Joe Pasternak, a producer known for whipping up innocuous crowd-pleasers (

Nancy Goes to Rio

,

Skirts Ahoy!

) that always came in on time and under budget. If an Arthur Freed film was vintage champagne, a Pasternak production was more like strawberry milk.

John Gay’s screenplay was based on a bestselling autobiographical novel by Mark Toby (with an uncredited assist from Dorothy Wilson). It told the story of Tom Corbett, a widowed radio executive coming to terms with his wife’s untimely death while caring for his son Eddie, who even at the age of six proves to be an incredibly resourceful matchmaker.

“I really followed that thing. I mean, it was a beauty,” John Gay says of Toby’s novel. “I didn’t want to lose one line. Of course, I had to open up the story a little with New York and the talk show [subplot] and all of that but it was really a dream job, you know? And this time, it turned out to be a perfect part for Glenn Ford.”

6

In Minnelli’s eyes, Ford would deliver a performance both “touching” and “true” as the Upper West Side’s most coveted bachelor father. The character of a single man balancing parenthood and professional obligations was one that Vincente could certainly relate to, having assumed that role in his own life.

6

In Minnelli’s eyes, Ford would deliver a performance both “touching” and “true” as the Upper West Side’s most coveted bachelor father. The character of a single man balancing parenthood and professional obligations was one that Vincente could certainly relate to, having assumed that role in his own life.

There is a genuine tenderness and poignancy to the film’s father-son exchanges in school hallways, breakfast nooks, and summer camps. The bond between Tom (Glenn Ford) and his precocious Eddie (Ron Howard) could have been patterned after Vincente’s own relationship with Liza. Minnelli usually interacted with his eldest daughter as though she were a pint-sized cocktail-party companion. “While other kids were hearing about Heidi and her goats, I was learning about Colette and her gentlemen,” Liza remembered.

7

7

Like

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Minnelli’s latest effort boasted a bravura performance by a child performer. Eight-year-old Ronny Howard, best known as “Opie” on

The Andy Griffith Show

, would shoot

Eddie’s Father

while his hit series was on hiatus. “I was fascinated by Vincente Minnelli,” Howard

would later recall. “I remember that he was photographing

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

a lot differently than the way the Andy Griffith shows were done. . . . My first exposure to a crane was Vincente Minnelli up there. The way he could handle that thing—it was just incredible.”

8

While Howard may have been fascinated by his director, the rest of the cast was fascinated by him.

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Minnelli’s latest effort boasted a bravura performance by a child performer. Eight-year-old Ronny Howard, best known as “Opie” on

The Andy Griffith Show

, would shoot

Eddie’s Father

while his hit series was on hiatus. “I was fascinated by Vincente Minnelli,” Howard

would later recall. “I remember that he was photographing

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

a lot differently than the way the Andy Griffith shows were done. . . . My first exposure to a crane was Vincente Minnelli up there. The way he could handle that thing—it was just incredible.”

8

While Howard may have been fascinated by his director, the rest of the cast was fascinated by him.

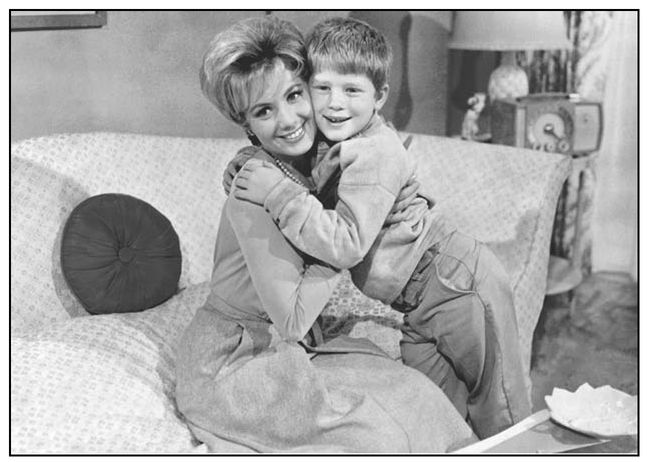

The Courtship of Eddie’s Father

featured two future television icons, Shirley Jones and Ron Howard. “I was fascinated by Vincente Minnelli,” recalled Howard, who went on to helm his own films. “My first exposure to a crane was Vincente Minnelli up there. The way he could handle that thing—it was just incredible.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

featured two future television icons, Shirley Jones and Ron Howard. “I was fascinated by Vincente Minnelli,” recalled Howard, who went on to helm his own films. “My first exposure to a crane was Vincente Minnelli up there. The way he could handle that thing—it was just incredible.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

“Ron Howard was never a child,” says Stella Stevens, who played Dollye Daly, the wide-eyed masher magnet “picked up” by both father and son. “I think Ron Howard probably came out of the womb acting . . .

Ta da! Here I am! I’m going to sing and dance and work.

He was like an old man trapped in a boy’s body. He was great as a child and wonderful to work with. When I see him in that movie, he makes me cry every time, especially when his goldfish dies.”

9

Ta da! Here I am! I’m going to sing and dance and work.

He was like an old man trapped in a boy’s body. He was great as a child and wonderful to work with. When I see him in that movie, he makes me cry every time, especially when his goldfish dies.”

9

For a light family comedy, there are some unsettling emotions lurking in the shadows of the story. Minnelli’s knack for transforming such everyday occurrences as moving out of the neighborhood or the death of a pet into arias of childhood anguish is indelibly displayed in one sequence. Distraught over his mother’s death, Eddie loses it when he discovers one of his goldfish

has also succumbed. While child actors in other films might shed glycerin tears or set their lower lips to quivering to indicate despair, Vincente encouraged his young performers to completely freak out. As essayist Carlos Losilla has observed, “[Minnelli] understands that one should film not only the body but the psychology of the infantile mind racked by pain.”

10

has also succumbed. While child actors in other films might shed glycerin tears or set their lower lips to quivering to indicate despair, Vincente encouraged his young performers to completely freak out. As essayist Carlos Losilla has observed, “[Minnelli] understands that one should film not only the body but the psychology of the infantile mind racked by pain.”

10

Eddie’s fear of death (his mother has died only days before the story begins) is mirrored in all of the lonely grown-ups he encounters. Every adult in Eddie’s universe is attempting to step out of a self-protective shell and forge a meaningful connection with another person. In their search for a surrogate wife/mother, Tom and Eddie meet the Three Faces of Woman (according to the very narrow definition of 1962): saintly nurse (Shirley Jones), sweet sexpot (Stella Stevens), and steely fashionista (Dina Merrill). “We were very lucky. They all turned out to be very good casting,” John Gay says of the leading ladies who starred as

Courtship

’s blonde, brunette, and redhead. This talented trio of actresses not only had to contend with a natural scene-stealer in the form of their young costar but also a director who sometimes confused his actors with what Stevens described as “decor de Minnelli.”

11

Courtship

’s blonde, brunette, and redhead. This talented trio of actresses not only had to contend with a natural scene-stealer in the form of their young costar but also a director who sometimes confused his actors with what Stevens described as “decor de Minnelli.”

11

“He was not necessarily an actor’s director,” says Shirley Jones, who was cast in

Courtship

fresh from her Oscar-winning turn in

Elmer Gantry

. “He sort of moved you around like a piece of scenery. I found it more difficult to work with Vincente than I had with several other directors that I had worked with earlier. But the result of what he did was always extraordinary. . . . I felt that I needed more direction from him, but that’s not the way he worked.”

12

Courtship

fresh from her Oscar-winning turn in

Elmer Gantry

. “He sort of moved you around like a piece of scenery. I found it more difficult to work with Vincente than I had with several other directors that I had worked with earlier. But the result of what he did was always extraordinary. . . . I felt that I needed more direction from him, but that’s not the way he worked.”

12

Dina Merrill, cast as Eddie’s “skinny-eyed” adversary, Rita Behrens, also recalled that actors weren’t exactly a top priority for the scenically obsessed Minnelli. “He was more concerned, it seemed to me, with painting a picture than he was with the performances. You had to kind of go on your own for the performances.”

13

13

Of the three, only Stella Stevens (singled out for praise in Minnelli’s memoir) was completely sold: “I’ve often said that Vincente was my favorite director. . . . You know, most directors don’t pay much attention to the women [in a film] but this man took a long time to talk to me about the part, so that we both understood what I was doing. . . . I would argue with a signpost. I would never argue with Vincente. He knew his stuff. He was a true genius.”

14

14

Released in March 1963, Minnelli’s comedy garnered generally favorable reviews, though

Cue

noted: “The story is too, too familiar; Vincente Minnelli directed it in Panavision and high-glossy Metrocolor, and Joe Pasternak produced. Joe is always happiest when he is making happy pictures about happy people with happy problems. Everybody’s happy, except sometimes the audience.”

Cue

noted: “The story is too, too familiar; Vincente Minnelli directed it in Panavision and high-glossy Metrocolor, and Joe Pasternak produced. Joe is always happiest when he is making happy pictures about happy people with happy problems. Everybody’s happy, except sometimes the audience.”

33

Identity Theft

AFTER VINCENTE LOST OUT on his opportunity to direct the highly anticipated screen version of

My Fair Lady

, many of his admirers found themselves playing the “What if? . . .” game. What if . . . he had directed Audrey Hepburn’s Eliza? Or what if Minnelli had helmed

Gypsy

instead of Mervyn LeRoy? What if his plans for a biopic of bisexual blues singer Bessie Smith had actually come off? In the latter half of Minnelli’s career, there seemed to be missed opportunities aplenty—such as Irving Berlin’s

Say It with Music

. MGM touted this “super spectacular” as though it were the greatest thing to happen to movies since the advent of sound.

My Fair Lady

, many of his admirers found themselves playing the “What if? . . .” game. What if . . . he had directed Audrey Hepburn’s Eliza? Or what if Minnelli had helmed

Gypsy

instead of Mervyn LeRoy? What if his plans for a biopic of bisexual blues singer Bessie Smith had actually come off? In the latter half of Minnelli’s career, there seemed to be missed opportunities aplenty—such as Irving Berlin’s

Say It with Music

. MGM touted this “super spectacular” as though it were the greatest thing to happen to movies since the advent of sound.

“When you decide to go ahead on a big picture, go with the pros—and the .400 hitters,” said MGM’s vice president, Robert Weitman, at a studio press conference in April 1963.

1

The heavy hitters Weitman had assembled included Arthur Freed, Vincente Minnelli, and Irving Berlin. They were joining forces to mount an ambitious, multimillion-dollar musical tentatively entitled

Say It with Music

. The score would include a cavalcade of Berlin standards and seven new songs by the celebrated composer of “God Bless America” and “White Christmas.” Arthur Laurents was tapped to write the screenplay. Jerome Robbins was lined up to choreograph a ragtime ballet. Robert Goulet would star as a globe-trotting lothario who romances beautiful women around the world, including Sophia Loren, Julie Andrews, and Ann-Margret.

1

The heavy hitters Weitman had assembled included Arthur Freed, Vincente Minnelli, and Irving Berlin. They were joining forces to mount an ambitious, multimillion-dollar musical tentatively entitled

Say It with Music

. The score would include a cavalcade of Berlin standards and seven new songs by the celebrated composer of “God Bless America” and “White Christmas.” Arthur Laurents was tapped to write the screenplay. Jerome Robbins was lined up to choreograph a ragtime ballet. Robert Goulet would star as a globe-trotting lothario who romances beautiful women around the world, including Sophia Loren, Julie Andrews, and Ann-Margret.

With such a staggering array of talent involved,

Say It with Music

was shaping up as a surefire, can’t miss, good old-fashioned Arthur Freed extravaganza.

Too bad it never got made. “Every time they were ready to shoot, the whole management of the studio changed,” says Barbara Freed Saltzman. “They would say, ‘Well, this is too expensive . . .’ or ‘We want to do something differently with this. . . .’ The people who made the decisions changed. They became much more business oriented and less artistic.”

2

Say It with Music

was shaping up as a surefire, can’t miss, good old-fashioned Arthur Freed extravaganza.

Too bad it never got made. “Every time they were ready to shoot, the whole management of the studio changed,” says Barbara Freed Saltzman. “They would say, ‘Well, this is too expensive . . .’ or ‘We want to do something differently with this. . . .’ The people who made the decisions changed. They became much more business oriented and less artistic.”

2

By 1968, Minnelli was out and Blake Edwards was in as director. After countless false starts and a ballooning budget, it looked as though

Say It with Music

was finally hitting the big screen. Edwards’s wife, Julie Andrews, was set to star in a 70-millimeter reserved-seat attraction. That is, until MGM was dismantled by its new studio chief, James Aubrey, who seemed far more interested in making real-estate deals than in making movies. Freed’s dream project died, and in essence, so did the studio where Vincente had spent more than two decades of his working life.

Say It with Music

was finally hitting the big screen. Edwards’s wife, Julie Andrews, was set to star in a 70-millimeter reserved-seat attraction. That is, until MGM was dismantled by its new studio chief, James Aubrey, who seemed far more interested in making real-estate deals than in making movies. Freed’s dream project died, and in essence, so did the studio where Vincente had spent more than two decades of his working life.

As the type of grand-scale musicals that Minnelli specialized in began to fall out of favor in the ’60s, the director was forced to turn his attention elsewhere and accept whatever projects were being offered to him. Sadly, several of Vincente’s later assignments didn’t seem well suited to his talents.

Goodbye, Charlie

, for example: George Axelrod’s comedy concerned Charlie Sorel, a chauvinistic screenwriter who is bumped off and then reincarnated as the kind of luscious little tomato he used to lust after (or, as the transformed Charlie puts it: “It’s as though I’ve been a gourmet all my life and now, suddenly, I’m a lamb chop”).

Goodbye, Charlie

, for example: George Axelrod’s comedy concerned Charlie Sorel, a chauvinistic screenwriter who is bumped off and then reincarnated as the kind of luscious little tomato he used to lust after (or, as the transformed Charlie puts it: “It’s as though I’ve been a gourmet all my life and now, suddenly, I’m a lamb chop”).

In 1959—the same year that Axelrod’s sex farce hit the Great White Way—moviegoers had lined up for Billy Wilder’s

Some Like It Hot

. Marilyn Monroe plus a gender-bending comedy added up to a mega-blockbuster. Hoping to duplicate the phenomenal success that United Artists had with the picture, 20th Century Fox snatched up the rights to

Goodbye, Charlie

with an eye toward developing the property for Monroe, the studio’s top star. Fox executives believed that Marilyn in the title role would result in an avalanche of box-office receipts. However, the actress didn’t see it that way at all: “The studio people want me to do

Goodbye, Charlie

for the movies, but I’m not going to do it. I don’t like the idea of playing a man in a woman’s body, you know? It just doesn’t seem feminine.”

3

Some Like It Hot

. Marilyn Monroe plus a gender-bending comedy added up to a mega-blockbuster. Hoping to duplicate the phenomenal success that United Artists had with the picture, 20th Century Fox snatched up the rights to

Goodbye, Charlie

with an eye toward developing the property for Monroe, the studio’s top star. Fox executives believed that Marilyn in the title role would result in an avalanche of box-office receipts. However, the actress didn’t see it that way at all: “The studio people want me to do

Goodbye, Charlie

for the movies, but I’m not going to do it. I don’t like the idea of playing a man in a woman’s body, you know? It just doesn’t seem feminine.”

3

In 1961, Vincente Minnelli’s name had appeared on the short list of directors that Monroe had agreed to work with (George Cukor, Alfred Hitchcock, and John Huston were among the others). And it’s possible that Fox may have secured Minnelli’s services in an attempt to entice Monroe to appear in

Goodbye, Charlie

. But to no avail. The star could not be persuaded,

av

and

in August 1962, she died of an overdose at the age of thirty-six. Nevertheless, Minnelli remained at the helm of the picture, and for the first time since his aborted stint at Paramount in the ’30s, he found himself working at a studio other than MGM.

Goodbye, Charlie

. But to no avail. The star could not be persuaded,

av

and

in August 1962, she died of an overdose at the age of thirty-six. Nevertheless, Minnelli remained at the helm of the picture, and for the first time since his aborted stint at Paramount in the ’30s, he found himself working at a studio other than MGM.

If Monroe had been ideal casting, her studio-sanctioned substitute, Debbie Reynolds, was not, though at the time the vivacious Reynolds was considered a theater-owner’s dream. Constantly in the headlines as the wronged wife in the Elizabeth Taylor-Eddie Fisher adultery scandal, and fresh from an Oscar-nominated tour de force in Metro’s high-spirited musical

The Unsinkable Molly Brown

, Reynolds was, in

Variety

parlance, “boffo box office.” While Reynolds virtually guaranteed brisk business at the ticket window, her cutie-pie chutzpah seemed wanting compared to Monroe’s triple-threat combination of vulnerability, sex appeal, and offbeat comedic timing.

The Unsinkable Molly Brown

, Reynolds was, in

Variety

parlance, “boffo box office.” While Reynolds virtually guaranteed brisk business at the ticket window, her cutie-pie chutzpah seemed wanting compared to Monroe’s triple-threat combination of vulnerability, sex appeal, and offbeat comedic timing.

MGM’s legendary acting coach Lillian Burns Sidney had advised Reynolds not to take the role of the gender-confused title character, as she was convinced that

Goodbye, Charlie

was essentially a one-joke story. But Reynolds wanted to work with Minnelli, so she signed on. “When one combines her self-possession with a tendency toward cuteness, you don’t get the exact quality I was looking for,” Minnelli would say of Reynolds.

4

However, Vincente was about to be reminded that Reynolds, who had survived Gene Kelly’s rigorous direction during

Singin’ in the Rain

, could be one of the hardest-working troopers in the business. Even if pert, wholesome Debbie was essentially miscast, she was determined to give

Goodbye, Charlie

her all.

Goodbye, Charlie

was essentially a one-joke story. But Reynolds wanted to work with Minnelli, so she signed on. “When one combines her self-possession with a tendency toward cuteness, you don’t get the exact quality I was looking for,” Minnelli would say of Reynolds.

4

However, Vincente was about to be reminded that Reynolds, who had survived Gene Kelly’s rigorous direction during

Singin’ in the Rain

, could be one of the hardest-working troopers in the business. Even if pert, wholesome Debbie was essentially miscast, she was determined to give

Goodbye, Charlie

her all.

Other books

Lacrimosa by Christine Fonseca

Next to Me by AnnaLisa Grant

Anthropology of an American Girl by Hilary Thayer Hamann

Equilateral by Ken Kalfus

Bonjour Cherie by Robin Thomas

The Cat Who Tailed a Thief by Lilian Jackson Braun

The Wanderers by Permuted Press

Spies (2002) by Frayn, Michael

King Lear by William Shakespeare