Mark Griffin (50 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

With everyone’s eyes trained on the bottom line, it’s no wonder that what emerged on-screen was, as critic John Simon put it, “straight Louisa May Alcott interlarded with discreet pornographic allusions.” Everywhere you turn,

The Sandpiper

is simply bad—though in many ways, deliciously so. “For me, just seeing Elizabeth Taylor holding a brush and palette makes the screen start vibrating,” says film historian Richard Barrios. “I kind of liken Liz as a painter to when you see Joan Crawford in her nurse’s uniform in

Possessed

. When you see someone who can only be a movie star trying to play some kind of working person, it’s ridiculous. . . . With

The Sandpiper

, you can really sense a talented director trying to do his best with what he’s been given to work with.”

6

The Sandpiper

is simply bad—though in many ways, deliciously so. “For me, just seeing Elizabeth Taylor holding a brush and palette makes the screen start vibrating,” says film historian Richard Barrios. “I kind of liken Liz as a painter to when you see Joan Crawford in her nurse’s uniform in

Possessed

. When you see someone who can only be a movie star trying to play some kind of working person, it’s ridiculous. . . . With

The Sandpiper

, you can really sense a talented director trying to do his best with what he’s been given to work with.”

6

An example of Metro gloss that has hardened into shellac, the movie offers plenty of camp compensations. MGM’s idea of a free-spirited beatnik is an ultra-glamorous Elizabeth Taylor, stunningly coiffed by Sydney Guilaroff, wrapped in a Sharaff poncho and dwelling in a palatial beach house direct from the pages of

Architectural Digest

. The entire movie follows suit. It’s a big, square commercial venture masquerading as 1965’s version of hip and cutting edge, complete with clean-cut, mild-mannered hippies sent over from central casting. There isn’t much that Minnelli could do with such an overblown “sex-on-the-sand soap opera,” except make sure it looked good—and this he did. Cinematographer Milton Krasner (an indispensable member of the expert team that now followed Minnelli from one picture to the next) captured some breathtaking images of the film’s two natural beauties: the violet-eyed Taylor and Big Sur.

Architectural Digest

. The entire movie follows suit. It’s a big, square commercial venture masquerading as 1965’s version of hip and cutting edge, complete with clean-cut, mild-mannered hippies sent over from central casting. There isn’t much that Minnelli could do with such an overblown “sex-on-the-sand soap opera,” except make sure it looked good—and this he did. Cinematographer Milton Krasner (an indispensable member of the expert team that now followed Minnelli from one picture to the next) captured some breathtaking images of the film’s two natural beauties: the violet-eyed Taylor and Big Sur.

If only the story was as arresting as the scenery. Taylor’s character, atheistic naturalist Laura Reynolds, may be the latest in a long line of Minnelli nonconformists, but she is unquestionably the blandest. It also doesn’t help that

all of the characters speak in beatific platitudes (“Thinking is almost always a kind of prayer . . .”) instead of more naturalistic dialogue. It’s nobody’s best work, but Eva Marie Saint manages one good scene when she tells Burton off. And Robert Webber is a lot of fun as Ward, the creepy swinger who punctuates nearly every sentence with “baby.”

all of the characters speak in beatific platitudes (“Thinking is almost always a kind of prayer . . .”) instead of more naturalistic dialogue. It’s nobody’s best work, but Eva Marie Saint manages one good scene when she tells Burton off. And Robert Webber is a lot of fun as Ward, the creepy swinger who punctuates nearly every sentence with “baby.”

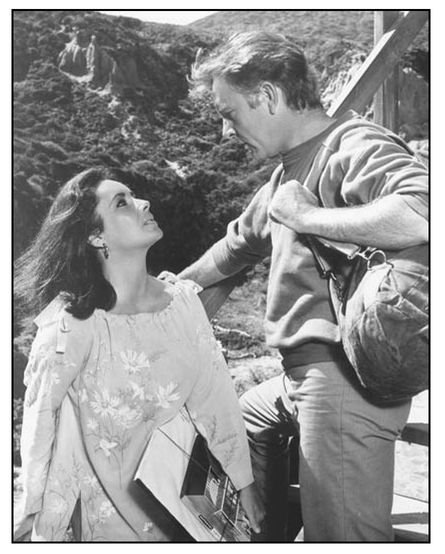

“The Shadow of Your Smile”: Laura Reynolds (Elizabeth Taylor) and Dr. Edward Hewitt (Richard Burton) go bohemian in

The Sandpiper

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The Sandpiper

. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Johnny Mandel and Paul Francis Webster’s haunting theme song, “The Shadow of Your Smile,” may be the only guilt-free pleasure associated with the movie. Recorded by everyone from Barbra Streisand to Pinky Winters, that lovely chart topper would win

The Sandpiper

its sole Oscar.

The Sandpiper

its sole Oscar.

35

“At Best, Confused”

IN 1932, DEPRESSION ERA AUDIENCES had flocked to see Greta Garbo as the exotic temptress Mata Hari. And forever after, the public would identify “The Swedish Sphinx” with the slinky secret agent. But to Vincente Minnelli, Mata Hari had always been a more complex figure—a question mark. Did the cooch-dancing vamp who called herself Mata Hari betray her legions of French lovers by passing their secrets on to the Germans? When the alluring femme fatale was executed by a firing squad, was she gunned down more for her loose morals than for her spying?

Vincente believed all of the ambiguity surrounding Mata Hari would make for compelling drama. “I wanted the audience to leave the theatre having great doubts about her,” Minnelli would say of the central character in the stage production of

Mata Hari

that he ended up directing in 1967. He certainly got his wish. The privileged few who saw her would leave the theater having great doubts not only about the subject but about nearly everything else connected with the show decades after it was staged.

Mata Hari

still ranks as one of the most notorious debacles in theatrical history—Vincente Minnelli’s very own

Springtime for Hitler

.

Mata Hari

that he ended up directing in 1967. He certainly got his wish. The privileged few who saw her would leave the theater having great doubts not only about the subject but about nearly everything else connected with the show decades after it was staged.

Mata Hari

still ranks as one of the most notorious debacles in theatrical history—Vincente Minnelli’s very own

Springtime for Hitler

.

In the beginning, a musicalized

Mata Hari

seemed like a sure thing. A trio of talented collaborators—Jerome Coopersmith (book), Edward Thomas (music), and Martin Charnin (lyrics)—had created an antiwar musical originally entitled

Ballad of a Firing Squad

. It retold the Mata Hari saga from the point of view of one of her lovers, Captain Henry LaFarge of French Military Intelligence. The musical juxtaposed Mata Hari’s exploits with

scenes in which a character known only as “The Young Soldier” marches off to the front lines. In a haunting song entitled “Maman,” the young but no longer innocent soldier sings the contents of a letter he has sent home to his mother:

“He was young, maman. He was small. I was trapped, maman, by a wall. Then he lunged, Maman, and I spun, face to face, Maman, gun to gun. Then and there, Maman, I could see . . . He was me, Maman. He was me. Just a boy, Maman, not a man . . . Can I kill, Maman? Yes I can.”

Mata Hari

seemed like a sure thing. A trio of talented collaborators—Jerome Coopersmith (book), Edward Thomas (music), and Martin Charnin (lyrics)—had created an antiwar musical originally entitled

Ballad of a Firing Squad

. It retold the Mata Hari saga from the point of view of one of her lovers, Captain Henry LaFarge of French Military Intelligence. The musical juxtaposed Mata Hari’s exploits with

scenes in which a character known only as “The Young Soldier” marches off to the front lines. In a haunting song entitled “Maman,” the young but no longer innocent soldier sings the contents of a letter he has sent home to his mother:

“He was young, maman. He was small. I was trapped, maman, by a wall. Then he lunged, Maman, and I spun, face to face, Maman, gun to gun. Then and there, Maman, I could see . . . He was me, Maman. He was me. Just a boy, Maman, not a man . . . Can I kill, Maman? Yes I can.”

Although ostensibly about World War I, the show seemed to offer up-to-the-minute commentary on the current political situation—the American occupation of Vietnam. “We were in a time of producing shows that had virtually no contemporary political or social significance,” recalls Martin Charnin. “The shows that were going on then were

The Happy Times

and

How Now, Dow Jones?

Stuff like that. We wanted to do something of real substance. . . . We thought that the Vietnamese experience and how ugly and terrifying the war was could be paralleled by virtue of the Mata Hari story.”

1

Charnin was slated to direct. All he and his partners needed was a producer willing to roll the dice.

The Happy Times

and

How Now, Dow Jones?

Stuff like that. We wanted to do something of real substance. . . . We thought that the Vietnamese experience and how ugly and terrifying the war was could be paralleled by virtue of the Mata Hari story.”

1

Charnin was slated to direct. All he and his partners needed was a producer willing to roll the dice.

In 1967, showman David Merrick was recovering from several recent failures, most notably a misguided musical version of

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

that featured Mary Tyler Moore as a singing, swearing Holly Golightly. This recent catastrophe aside, Merrick’s Broadway record spoke for itself:

Gypsy

,

Hello, Dolly!

and

Carnival

. If anybody could make a musical out of the legend of Mata Hari, it was Merrick. When Martin Charnin pitched the musical to Merrick, he was pleasantly surprised that the unpredictable producer seemed receptive to the concept—even the antiwar theme. What’s more, Merrick wanted to move ahead immediately—though with a director more experienced than Charnin (whose mega-smash

Annie

was still a decade away). Merrick believed that it was important to have a big name attached to such an ambitious, epically scaled production.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s

that featured Mary Tyler Moore as a singing, swearing Holly Golightly. This recent catastrophe aside, Merrick’s Broadway record spoke for itself:

Gypsy

,

Hello, Dolly!

and

Carnival

. If anybody could make a musical out of the legend of Mata Hari, it was Merrick. When Martin Charnin pitched the musical to Merrick, he was pleasantly surprised that the unpredictable producer seemed receptive to the concept—even the antiwar theme. What’s more, Merrick wanted to move ahead immediately—though with a director more experienced than Charnin (whose mega-smash

Annie

was still a decade away). Merrick believed that it was important to have a big name attached to such an ambitious, epically scaled production.

At that moment, Minnelli was once again a hot commodity in Hollywood, thanks to the announcement that he’d soon be directing Barbra Streisand in a lavishly budgeted screen version of the Broadway musical

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever

. But in terms of Broadway, Minnelli was about as sought after as an Actor’s Equity strike. In fact, the sixty-five-year-old Minnelli hadn’t directed a theatrical production since

Very Warm for May

, way back in 1938—when Zsa Zsa Gabor was still on her first husband. Despite Vincente’s former glories on the Great White Way, selecting him as the director of a piece that addressed the futility of war seemed ill-advised at best. “It was totally Merrick’s idea to have Minnelli as the director,” Charnin says.

“We were not given a choice. It was sprung on us. It was all about having a name director. Even though the name was a little musty. Even so, there was this gigantic cachet just in terms of Minnelli’s name value.”

2

Merrick would surround Minnelli with a team of top theater professionals, including designer Jo Mielziner and two transplants from Hollywood whom Vincente knew and respected—choreographer Jack Cole and designer Irene Sharaff.

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever

. But in terms of Broadway, Minnelli was about as sought after as an Actor’s Equity strike. In fact, the sixty-five-year-old Minnelli hadn’t directed a theatrical production since

Very Warm for May

, way back in 1938—when Zsa Zsa Gabor was still on her first husband. Despite Vincente’s former glories on the Great White Way, selecting him as the director of a piece that addressed the futility of war seemed ill-advised at best. “It was totally Merrick’s idea to have Minnelli as the director,” Charnin says.

“We were not given a choice. It was sprung on us. It was all about having a name director. Even though the name was a little musty. Even so, there was this gigantic cachet just in terms of Minnelli’s name value.”

2

Merrick would surround Minnelli with a team of top theater professionals, including designer Jo Mielziner and two transplants from Hollywood whom Vincente knew and respected—choreographer Jack Cole and designer Irene Sharaff.

For the role of Captain LaFarge, an actor with a powerful stage presence and voice to match was required. Yves Montand was offered the role but declined. Pernell Roberts, best known as Adam Cartwright on television’s highly rated

Bonanza

, agreed to star.

Bonanza

, agreed to star.

In terms of the crucial casting of the leading lady, it was not Vincente but Minnelli’s wife Denise Giganti who played talent scout. A stunning Viennese-born model regularly appearing in the pages of

Vogue

and

Harper’s Bazaar

had caught her eye. “It was Denise, who made the first contact with Marisa Mell,” Vincente recalled. “After they met in Rome and lunched together, Denise cabled back, ‘She’s your girl.’”

Washington Post Times Herald

reporter Eugenia Sheppard, however, noted that “since they spoke in Italian all through the luncheon, Mrs. Minnelli forgot to ask Marisa if she spoke English. She didn’t find out, either, whether she could sing.”

3

Vogue

and

Harper’s Bazaar

had caught her eye. “It was Denise, who made the first contact with Marisa Mell,” Vincente recalled. “After they met in Rome and lunched together, Denise cabled back, ‘She’s your girl.’”

Washington Post Times Herald

reporter Eugenia Sheppard, however, noted that “since they spoke in Italian all through the luncheon, Mrs. Minnelli forgot to ask Marisa if she spoke English. She didn’t find out, either, whether she could sing.”

3

Although Mell’s English was acceptable, many connected with the show recalled that her “singing” was not. In fact, prior to

Mata Hari

, Mell’s only musical experience had been a stint in an obscure European touring company of

Kiss Me Kate

. “Marisa Mell was only hired to be the lead because she was having an affair with Denise Minnelli,” says Hugh Fordin, who was David Merrick’s head of casting at the time.

4

Whether or not the rumors were true, a Broadway musical featuring a lead performer who could neither sing nor dance proved to be the tip of the iceberg.

Mata Hari

, Mell’s only musical experience had been a stint in an obscure European touring company of

Kiss Me Kate

. “Marisa Mell was only hired to be the lead because she was having an affair with Denise Minnelli,” says Hugh Fordin, who was David Merrick’s head of casting at the time.

4

Whether or not the rumors were true, a Broadway musical featuring a lead performer who could neither sing nor dance proved to be the tip of the iceberg.

As Fordin recalls:

I was casting

Mata Hari

for Minnelli and he had the nerve to have Elaine Stritch come in to audition for what turned out to be the Tessie O’Shea role in the second act—a flower girl. Ridiculous. . . . Minnelli turned to me during one of the audition days and said, “Remind me before we start to go into rehearsal, I want to run my movie of

The Band Wagon

for the whole company.” And instantly I knew what he was saying was that this was going to turn into that disaster in

The Band Wagon

—the musical version of

Faust

.

Mata Hari

for Minnelli and he had the nerve to have Elaine Stritch come in to audition for what turned out to be the Tessie O’Shea role in the second act—a flower girl. Ridiculous. . . . Minnelli turned to me during one of the audition days and said, “Remind me before we start to go into rehearsal, I want to run my movie of

The Band Wagon

for the whole company.” And instantly I knew what he was saying was that this was going to turn into that disaster in

The Band Wagon

—the musical version of

Faust

.

Even at the beginning, when I sat in the office to read that script and meet the three guys who created the show, Martin Charnin was not talking to Ed Thomas, the composer, nor was he talking to Jerome Coopersmith, the book

writer. This was even before Minnelli came in. And I went into Merrick and told him it was going to be a disaster and he said, “I don’t care. It’s not my money anyway. It’s RCA/Victor’s money.”

5

writer. This was even before Minnelli came in. And I went into Merrick and told him it was going to be a disaster and he said, “I don’t care. It’s not my money anyway. It’s RCA/Victor’s money.”

5

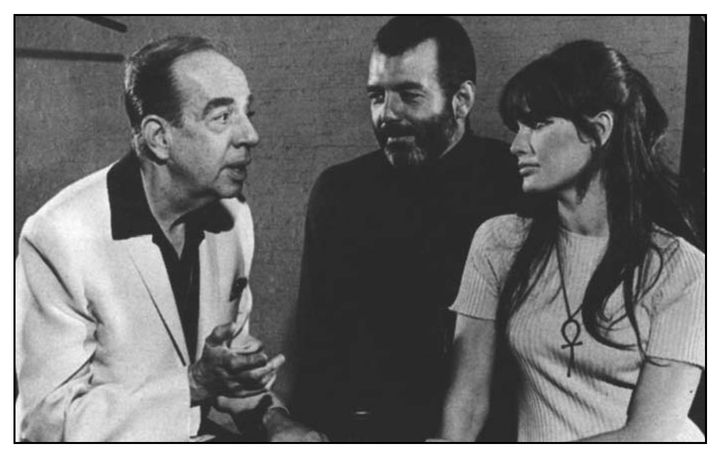

Minnelli rehearses Pernell Roberts and Marisa Mell for the ill-fated

Mata Hari

in 1967. “Jesus, what a nightmare it was . . .” dancer Antony DeVecchi says of the musical, which still ranks as one of the greatest debacles in theatrical history. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Mata Hari

in 1967. “Jesus, what a nightmare it was . . .” dancer Antony DeVecchi says of the musical, which still ranks as one of the greatest debacles in theatrical history. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The record label had ponied up most of the money for

Mata Hari

and planned to recoup part of the investment with the release of the original Broadway cast album. As fate would have it, neither the album nor

Mata Hari

on Broadway would ever materialize.

Mata Hari

and planned to recoup part of the investment with the release of the original Broadway cast album. As fate would have it, neither the album nor

Mata Hari

on Broadway would ever materialize.

There were signs of the disaster to come early on. Although the cast was excited to appear in a production helmed by the legendary Vincente Minnelli, they were dismayed to discover that their director still seemed to think that he was back on a Culver City soundstage. As dancer Antony DeVecchi remembered:

We’d all be ready to rehearse and Vincente would be sitting out in the audience, and he’d yell, “Camera! . . .

Action

!” And we’d say to each other, “What the fuck is going on?” We were used to direction like “Move downstage left,” you know? We were theater people. But it wasn’t his direction that killed the show. It was the script. It was just a lousy, uninteresting story. It didn’t only kill Vincente.

It killed all of us. Mata Hari was this nondescript character. Basically, she was a hooker screwing everything she could get. She didn’t have a brain. If Mata Hari had just been a supporting character who came in and left and you focused on the Deuxième Bureau, the FBI of France, we would still be running on Broadway.

6

Action

!” And we’d say to each other, “What the fuck is going on?” We were used to direction like “Move downstage left,” you know? We were theater people. But it wasn’t his direction that killed the show. It was the script. It was just a lousy, uninteresting story. It didn’t only kill Vincente.

It killed all of us. Mata Hari was this nondescript character. Basically, she was a hooker screwing everything she could get. She didn’t have a brain. If Mata Hari had just been a supporting character who came in and left and you focused on the Deuxième Bureau, the FBI of France, we would still be running on Broadway.

6

Others close to the production believed that Minnelli was the show’s primary problem. “I think he was lost,” says Martin Charnin:

To me, Vincente was very much living in a fantasy about what he thought the show was about. I mean, we had written a very dark musical, but Vincente was far more interested in whether or not there were enough crinolines in the dresses on stage. I mean, he had more meetings with Irene Sharaff than he had with the writers. Practically from minute one, the

Mata Hari

that we had created began to sink into this frou-frou world, and it never recovered. It was swallowed up by silk and feathers.

7

Mata Hari

that we had created began to sink into this frou-frou world, and it never recovered. It was swallowed up by silk and feathers.

7

Other books

The Breadth of Heaven by Rosemary Pollock

One Day (A Valentine Short Story) by Samantha Young

Lakota Dawn by Taylor, Janelle

Jade Dragon Mountain by Elsa Hart

Prowler: Forsaken Ones MC by Leah Wilde

Island Heat (A Sexy Time Travel Romance With a Twist) by Myles, Jill

Captain Nemo: The Fantastic History of a Dark Genius by Kevin J. Anderson

Strapless by Davis, Deborah

SubmittingtotheRake by Em Brown