Mark Griffin (30 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Determined to avoid becoming a cinematic cliché, Houseman wisely decided to shift the story’s setting from Broadway to Hollywood. There may have been another reason for this transition, too, and it was called

Sunset Boulevard

. Billy Wilder’s sardonic masterpiece had copped three Oscars in 1950, and although Louis B. Mayer would berate Wilder (“You befouled your own nest”

2

), he and every other executive in town were keenly aware of how much acclaim the self-reflexive saga of Norma Desmond had garnered. Houseman assigned screenwriter Charles Schnee to rework “Memorial to a Bad Man.” In addition to making the story more cinematic, Schnee would also work in plot elements from Bradshaw’s similarly themed

Cosmopolitan

novelette “Of Good and Evil.”

Sunset Boulevard

. Billy Wilder’s sardonic masterpiece had copped three Oscars in 1950, and although Louis B. Mayer would berate Wilder (“You befouled your own nest”

2

), he and every other executive in town were keenly aware of how much acclaim the self-reflexive saga of Norma Desmond had garnered. Houseman assigned screenwriter Charles Schnee to rework “Memorial to a Bad Man.” In addition to making the story more cinematic, Schnee would also work in plot elements from Bradshaw’s similarly themed

Cosmopolitan

novelette “Of Good and Evil.”

When Schnee’s script was ready, Houseman summoned Minnelli to lunch at Romanoff’s. As Vincente later recalled, “The screenplay fascinated me. It told of a film producer who uses everyone in his rise to the top. . . . It was a harsh and cynical story, yet strangely romantic. All that one loved and hated about Hollywood was distilled in the screenplay.”

3

3

What’s more, Minnelli recognized that the characters (now more Schnee than Bradshaw) would register as more authentic if they were patterned after real-life models: First there was Jonathan Shields, the unscrupulous producer who rose from the B-movie junk heap. Shields seemed to be a clever composite of

Cat People

producer Val Lewton and Louis B. Mayer’s former son-in-law, the fanatically involved David O. Selznick. Then there was Georgia Lorrison, the boozy has-been who deifies her dead father and scrapes her way to stardom, reportedly modeled on John Barrymore’s daughter Diana. Henry Whitfield, a British director with a taste for the macabre, could have been either Alfred Hitchcock or James Whale. The even more exacting auteur Von Ellstein seemed reminiscent of Fritz Lang or Erich von Stroheim. All of these roles were camouflaged just enough to keep everyone guessing with a general “Wait a minute,

Is that supposed to be

? . . .” effect permeating the entire picture—exactly the kind of illusion-on-an-illusion that Minnelli and Houseman had hoped to achieve.

ag

Cat People

producer Val Lewton and Louis B. Mayer’s former son-in-law, the fanatically involved David O. Selznick. Then there was Georgia Lorrison, the boozy has-been who deifies her dead father and scrapes her way to stardom, reportedly modeled on John Barrymore’s daughter Diana. Henry Whitfield, a British director with a taste for the macabre, could have been either Alfred Hitchcock or James Whale. The even more exacting auteur Von Ellstein seemed reminiscent of Fritz Lang or Erich von Stroheim. All of these roles were camouflaged just enough to keep everyone guessing with a general “Wait a minute,

Is that supposed to be

? . . .” effect permeating the entire picture—exactly the kind of illusion-on-an-illusion that Minnelli and Houseman had hoped to achieve.

ag

In December 1951, Hedda Hopper had announced to her readers that MGM hoped to entice Clark Gable to play Jonathan Shields. When that casting didn’t pan out, producer and director had only one other actor in mind for the wily, backstabbing heel you love to hate: Kirk Douglas.

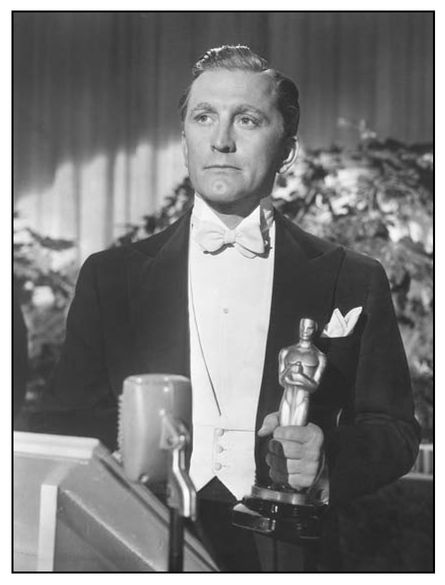

Tribute to a Bad Man:

Ruthless producer Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) cops the Oscar in a sequence deleted from the release print of

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Douglas said of his director: “He was a genius and for whatever reason, that has never been properly recognized.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Ruthless producer Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas) cops the Oscar in a sequence deleted from the release print of

The Bad and the Beautiful

. Douglas said of his director: “He was a genius and for whatever reason, that has never been properly recognized.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

“I was the teacher’s pet,” Douglas says of working with Minnelli on the first of their three pictures together:

We seemed to be on the same wavelength. We were so different but we seemed to understand each other very well. He told me something and I got it the first time. I never had such gratification making a movie than I did with Vincente Minnelli. You know, he was an unusual guy. He was always humming and he was always rearranging the props all over the set but he really knew what he was doing. He was a perfectionist—without question. And he was always annoyed with everybody but me. He would smile at me with approval and then he would snap at someone else. Sometimes he could be very impatient and irritable with incompetence in an actor. But we never had a problem.

In his own way, I think Vincente had a tremendous sense of humor, which would come out in some of the most unusual ways. . . . I liked him so much. He encouraged me in everything that I did and, as an actor, I think that I blossomed under his direction. He was a genius and for whatever reason, that has never been properly recognized.

4

4

As Douglas began shaping his performance, Minnelli suggested that the actor soft-pedal his trademark intensity and “play it for charm.” The suggestion worked so well that Douglas, like his character, was charm personified. “Kirk’s behavior was exemplary,” Houseman would recall, refuting rumors that the photogenic leading man could be prickly and hot headed. “He was up on the lines of his huge role—indefatigable, intelligent and receptive to Minnelli’s direction.”

5

5

Another surprise was leading lady Lana Turner, who campaigned for the role of Georgia Lorrison. After her latest outings,

The Merry Widow

,

Mr. Imperium

, and

A Life of Her Own

,

ah

all tanked at the box office, Turner knew that her career was desperately in need of rehabilitation. The role of the gin-soaked starlet who rises to fame seemed like just the ticket. “When the script reached me, I knew right away that I understood the character—a film star who is seen at first as a soggy mess and then is resuscitated by an unscrupulous producer,” Turner said. “I could believe in her. Moreover, the screenplay was a much better one than those I usually received.”

6

And how.

The Merry Widow

,

Mr. Imperium

, and

A Life of Her Own

,

ah

all tanked at the box office, Turner knew that her career was desperately in need of rehabilitation. The role of the gin-soaked starlet who rises to fame seemed like just the ticket. “When the script reached me, I knew right away that I understood the character—a film star who is seen at first as a soggy mess and then is resuscitated by an unscrupulous producer,” Turner said. “I could believe in her. Moreover, the screenplay was a much better one than those I usually received.”

6

And how.

For once, Turner’s costume changes would not be substituted for legitimate character development. This would be the “sweater girl’s” meatiest role since her memorable turn as the white-turbaned femme fatale in

The Postman Always Rings Twice

in 1946. And Minnelli was determined to extract a real performance from Turner—one that, ironically, called for her to strip away her movie star veneer in order to play a movie star. For her first scene in the picture, Turner is present only as a disembodied voice (as Georgia lurks in the shadows of Crow’s Nest, her late father’s decaying mansion)—a legitimate challenge for an actress accustomed to relying on her physical gifts to make an impression.

The Postman Always Rings Twice

in 1946. And Minnelli was determined to extract a real performance from Turner—one that, ironically, called for her to strip away her movie star veneer in order to play a movie star. For her first scene in the picture, Turner is present only as a disembodied voice (as Georgia lurks in the shadows of Crow’s Nest, her late father’s decaying mansion)—a legitimate challenge for an actress accustomed to relying on her physical gifts to make an impression.

Metro veteran Walter Pidgeon convinced Minnelli that he could check his Brooks Brothers persona at the door and play the penny-pinching producer Harry Pebbel, who only wants “pictures that end with a kiss and black ink on the books.” Originally, Barry Sullivan was cast as southern novelist James Lee Bartlow and Dick Powell was scheduled to play director Fred Amiel. Powell (who was still an important marquee draw at that time), immediately realized that the gentrified novelist was a better part, and he asked Minnelli and Houseman to cast him as Bartlow and reassign Sullivan as the director. They complied. The one and only Gloria Grahame (she of the insolent pout and bee-stung lips) was cast as the writer’s wife, “a modern day Southern

belle,” at the suggestion of Houseman, who said of the actress: “She had an instinctive talent complicated by a number of peculiar aberrations—including a taste for facial surgery that she did not need.”

7

belle,” at the suggestion of Houseman, who said of the actress: “She had an instinctive talent complicated by a number of peculiar aberrations—including a taste for facial surgery that she did not need.”

7

Kirk Douglas, Paul Stewart, Vanessa Brown, Barry Sullivan, and singer Peggy King in a party sequence from

The Bad and the Beautiful

. King’s bit part was inspired by Judy Garland’s impromptu vocal performances at Hollywood parties. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The Bad and the Beautiful

. King’s bit part was inspired by Judy Garland’s impromptu vocal performances at Hollywood parties. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Even with his formidable line-up of stars in place, Minnelli continued casting—supporting roles, bit players, and walk-ons. In a Vincente Minnelli production, there was no such thing as a small part. “I was doing a cameo in the picture but he directed me as if it was the most important scene in any film he ever directed,” says singer Peggy King, who performs the haunting ballad “Don’t Blame Me”

ai

in a party sequence. “It was very strange being a starlet at Metro in those days. Everybody was doing stuff behind everybody else’s back. But not Vincente. He was so wonderful. He treated me as if I were on an equal footing with Kirk and Lana and the other stars. . . . Wasn’t

I lucky that if I was going to do a cameo in a picture that it turned out to be that one and with Minnelli as the director?”

8

ai

in a party sequence. “It was very strange being a starlet at Metro in those days. Everybody was doing stuff behind everybody else’s back. But not Vincente. He was so wonderful. He treated me as if I were on an equal footing with Kirk and Lana and the other stars. . . . Wasn’t

I lucky that if I was going to do a cameo in a picture that it turned out to be that one and with Minnelli as the director?”

8

Houseman fought to have the film photographed in color and to retain the story’s original title, but he lost the battle on both counts. With Turner receiving top billing over Douglas, it was suggested that a more romantically attuned title was in order. MGM’s chief publicist, Howard Dietz, suggested

The Bad and the Beautiful

, and despite Houseman’s very vocal objections, it stuck. Production began on April 9, 1952.

The Bad and the Beautiful

, and despite Houseman’s very vocal objections, it stuck. Production began on April 9, 1952.

Musicals aside,

The Bad and the Beautiful

would contain some of the most indelible images that Minnelli would ever capture on film, including Shields paying off the mourners-for-hire at his despised father’s funeral (“He lived in a crowd, I couldn’t let him be buried alone . . .”) and Georgia’s ascent to superstardom, which Minnelli accomplishes in one magnificently fluid transition: After capturing Georgia’s performance on the set, the camera sails all the way up to the soundstage rafters, where several seen-it-all grips and electricians are beaming with pride: a blazing arc light that one of them is operating morphs into a blinding klieg light on the eve of Georgia’s big premiere. The star trip in shorthand. This is followed by Lana’s gloriously over-the-top vehicular nervous breakdown, which critic Tom Shales would salute as “one of the great melodramatic arias ever staged for a film.”

9

And who can forget character actor Ned Glass as a grizzled wardrobe man peddling some unintentionally hilarious cat suits (“lots of character in the tail . . .”) for Jonathan’s low-budget horror flick

The Doom of the Cat Men

.

The Bad and the Beautiful

would contain some of the most indelible images that Minnelli would ever capture on film, including Shields paying off the mourners-for-hire at his despised father’s funeral (“He lived in a crowd, I couldn’t let him be buried alone . . .”) and Georgia’s ascent to superstardom, which Minnelli accomplishes in one magnificently fluid transition: After capturing Georgia’s performance on the set, the camera sails all the way up to the soundstage rafters, where several seen-it-all grips and electricians are beaming with pride: a blazing arc light that one of them is operating morphs into a blinding klieg light on the eve of Georgia’s big premiere. The star trip in shorthand. This is followed by Lana’s gloriously over-the-top vehicular nervous breakdown, which critic Tom Shales would salute as “one of the great melodramatic arias ever staged for a film.”

9

And who can forget character actor Ned Glass as a grizzled wardrobe man peddling some unintentionally hilarious cat suits (“lots of character in the tail . . .”) for Jonathan’s low-budget horror flick

The Doom of the Cat Men

.

“If you look at the cat man sequence in

The Bad and the Beautiful

, nobody else would have done that in quite the way he did that,” says writer and Minnelli enthusiast Sir Gerald Kaufman:

The Bad and the Beautiful

, nobody else would have done that in quite the way he did that,” says writer and Minnelli enthusiast Sir Gerald Kaufman:

Or that scene at the end with all of them clustering around the telephone, listening to what was being said by Jonathan Shields on the other end—I can’t imagine another director staging it that way. Despite the difficulties of the Hollywood studio system, it’s perfectly clear in my mind that Minnelli put an enormous amount of himself into his films. I can’t think of another Hollywood director, except, say, John Ford or Alfred Hitchcock, whose films were theirs in the same way that Minnelli’s films were his. I mean, let’s face it, MGM was there to make films to make money. . . . They wouldn’t have kept him as long as they did or allow him to make all kinds of films—a western like

Home from the Hill

or a comedy like

The Long, Long Trailer

—if they didn’t have enormous confidence in him. He wasn’t just a journeyman director. He was a totally unique director. And you can see that in every frame of

The Bad and the Beautiful

.

10

Home from the Hill

or a comedy like

The Long, Long Trailer

—if they didn’t have enormous confidence in him. He wasn’t just a journeyman director. He was a totally unique director. And you can see that in every frame of

The Bad and the Beautiful

.

10

Film audiences of the day may have relished what appeared to be a privileged glimpse of the world behind the screen, but it was “real life,” according to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Composer David Raksin, who would furnish the film with one of the most haunting themes in movie history, summed it up perfectly: “This is no mere photograph of Hollywood but rather a romantically diffused look into a mirror. . . . When it looks at scars and wrinkles, it is with a lover’s eye.”

11

11

The sweet and sour tone sustained throughout

The Bad and the Beautiful

does feel authentic, and who better to direct a study of driven careerists in the business of manufacturing illusion than Minnelli, who by that time had seen more than his fair share of bad and beautiful. Although Vincente is adept at handling the cynical tone, it is the cynicism of a die-hard romantic who still believes in happy endings, Hollywood style.

The Bad and the Beautiful

does feel authentic, and who better to direct a study of driven careerists in the business of manufacturing illusion than Minnelli, who by that time had seen more than his fair share of bad and beautiful. Although Vincente is adept at handling the cynical tone, it is the cynicism of a die-hard romantic who still believes in happy endings, Hollywood style.

On September 18, 1952,

The Bad and the Beautiful

was previewed in Pacific Palisades. Of the 160 preview cards returned, 44 audience members rated the film “outstanding” and 67 thought it was “excellent,” though many patrons grumbled about the film’s length. As a result, some footage was excised—including an elaborate Peter Ballbusch “star-seeing” montage—before the picture was released in January 1953.

The Bad and the Beautiful

was previewed in Pacific Palisades. Of the 160 preview cards returned, 44 audience members rated the film “outstanding” and 67 thought it was “excellent,” though many patrons grumbled about the film’s length. As a result, some footage was excised—including an elaborate Peter Ballbusch “star-seeing” montage—before the picture was released in January 1953.

“Let’s say that any resemblance to persons living or dead is hardly a coincidence,” wrote Josh Rosenfield in his

Dallas Morning News

review. “The picture is a directorial feat for Vincente Minnelli, who shows imposing stature. He holds all the strands of a complicated story in tight rein. He gives the whole a treatment of unexpected twists.”

12

Dallas Morning News

review. “The picture is a directorial feat for Vincente Minnelli, who shows imposing stature. He holds all the strands of a complicated story in tight rein. He gives the whole a treatment of unexpected twists.”

12

Other books

Casca 3: The Warlord by Barry Sadler

Anonymous Sources by Mary Louise Kelly

30 - It Came from Beneath the Sink by R.L. Stine - (ebook by Undead)

An Unfinished Score by Elise Blackwell

First Sight by Donohue, Laura

Letters From a Cat: Published by Her Mistress for the Benefit of All Cats and the Amusement of Little Children by Ledyard Addie, Helen Hunt 1830-1885 Jackson

All or Nothing by Dee Tenorio

Heart of Gold by Beverly Jenkins

Lace & Lassos by Cheyenne McCray

CHERUB: Maximum Security by Robert Muchamore