Mark Griffin (27 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Musical supervisor Saul Chaplin, on the other hand, was all too aware of how unique Production #1507 was. “All I can say is that I never worked on any score that I had more respect for, and that I did so carefully,” said Chaplin, who combed through countless compositions in the Gershwin catalog, not only selecting numbers for musical sequences but also themes for the film’s underscoring. All the while, Chaplin was conscious of the specter of George Gershwin hovering over the project, “I must have chosen 50 songs that absolutely

had

to be in the picture. . . . I was careful and I was worried. I was

careful because I wanted to make sure it came out to the best of my ability, to see if I could match the master. And worried that I might be doing something wrong.”

7

had

to be in the picture. . . . I was careful and I was worried. I was

careful because I wanted to make sure it came out to the best of my ability, to see if I could match the master. And worried that I might be doing something wrong.”

7

Chaplin said that he “considered George Gershwin ‘God,’” a reverence shared by Minnelli, Levant, and virtually everyone connected with the film. It almost went without saying that as a cinematic tribute, the climactic

American in Paris

ballet would have to be extraordinary. There had been ambitious, even groundbreaking ballets featured in Metro musicals before—Astaire’s surrealist spin in

Yolanda and the Thief

, Kelly’s memorable “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” in

Words and Music

—but in retrospect, those efforts would seem like elaborate dress rehearsals for what would ultimately be proclaimed “MGM’s masterpiece.”

American in Paris

ballet would have to be extraordinary. There had been ambitious, even groundbreaking ballets featured in Metro musicals before—Astaire’s surrealist spin in

Yolanda and the Thief

, Kelly’s memorable “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” in

Words and Music

—but in retrospect, those efforts would seem like elaborate dress rehearsals for what would ultimately be proclaimed “MGM’s masterpiece.”

“We had no definite plan for the ballet all the while we were shooting the book,” Minnelli told author Donald Knox:

We knew in a vague way that it had to incorporate parts of Paris that artists had painted, but we had no time to figure this out until Nina Foch came down with chicken pox. There was nothing left to shoot whatsoever, so Irene Sharaff, who I had hired to design the costumes, and Gene Kelly and I locked ourselves in my office for hours and hours and hours on end. We worked out the entire ballet during those days. It was the luckiest chicken pox I’ve ever known.

8

8

At first, an all-too-literal Parisian ballet was proposed. Kelly would romp through the City of Light’s most enchanting boulevards in a variation on his on-location ramble through Manhattan in

On the Town

. To Freed, this seemed redundant. And to Minnelli and his colleagues, it was clear that something more

psychological

was in order—which is what George Gershwin appeared to have in mind to begin with: “The individual listener can read into the music such as his imagination pictures for him,” Gershwin said of his orchestral tone poem, which had debuted at Carnegie Hall in 1928.

9

For Minnelli, reading into the music resulted in plenty of pictures—all of them by the Impressionists. Cued by the varying moods of the music, each section of the ballet would feature settings, costumes, and styles of dance inspired by masterworks by Henri Rousseau, Raoul Dufy, and Vincent van Gogh.

On the Town

. To Freed, this seemed redundant. And to Minnelli and his colleagues, it was clear that something more

psychological

was in order—which is what George Gershwin appeared to have in mind to begin with: “The individual listener can read into the music such as his imagination pictures for him,” Gershwin said of his orchestral tone poem, which had debuted at Carnegie Hall in 1928.

9

For Minnelli, reading into the music resulted in plenty of pictures—all of them by the Impressionists. Cued by the varying moods of the music, each section of the ballet would feature settings, costumes, and styles of dance inspired by masterworks by Henri Rousseau, Raoul Dufy, and Vincent van Gogh.

Having settled on the visual look of the ballet, Minnelli and company next turned to the matter of theme. “Gene thought you had to have a story,” Vincente remembered. “I said, ‘You can’t have a story because if it’s a new story, that’s bewildering. . . . I said, ‘It has to be something to do with

emotions

, the time in his mind, the way he feels having just lost his girl, and a whole

thing about Paris.’ Everything had to become a jumble in his mind, a kind of delirium because Leslie’s leaving him hits him so hard.”

10

emotions

, the time in his mind, the way he feels having just lost his girl, and a whole

thing about Paris.’ Everything had to become a jumble in his mind, a kind of delirium because Leslie’s leaving him hits him so hard.”

10

Once the production team convinced themselves that their idea for an Impressionistic ballet was sound, they had to turn around and sell it to the powers that be. As Gene Kelly recalled, “Dore Schary had now taken over Mayer’s job as head of production, so we brought all the sketches to him and gulped and cleared our throats and said, ‘You know, we want to do this ballet . . .’ and I described it. He finally said, ‘Wait a minute. Wait a minute! I don’t understand one word that you’re all talking about but, you know something, it looks good and I trust you people. . . . Get out of here and go and do it.’”

For the reunited team of Minnelli and Kelly, the division of duties that existed on

The Pirate

continued through

An American in Paris

. For Kelly, as both star and choreographer, the film—and particularly the ballet—provided an opportunity for the kind of virtuosic tour de force that he’d been building toward since his debut in

For Me and My Gal

nearly a decade earlier.

The Pirate

continued through

An American in Paris

. For Kelly, as both star and choreographer, the film—and particularly the ballet—provided an opportunity for the kind of virtuosic tour de force that he’d been building toward since his debut in

For Me and My Gal

nearly a decade earlier.

Whereas other directors would brook no interference from

some actor

, Minnelli was smart enough to know when to let a collaborator do what he or she did best for the benefit of the picture. As Alan Jay Lerner expressed it, “Vincente doesn’t try to do your creating for you. . . . Vincente knows the direction, but he will let you drive.”

11

Relinquishing the reins to Kelly was also a practical necessity, as Minnelli was contractually obligated to direct

Father’s Little Dividend

,

ae

the pleasant though pedestrian sequel to

Father of the Bride

, at the same time.

some actor

, Minnelli was smart enough to know when to let a collaborator do what he or she did best for the benefit of the picture. As Alan Jay Lerner expressed it, “Vincente doesn’t try to do your creating for you. . . . Vincente knows the direction, but he will let you drive.”

11

Relinquishing the reins to Kelly was also a practical necessity, as Minnelli was contractually obligated to direct

Father’s Little Dividend

,

ae

the pleasant though pedestrian sequel to

Father of the Bride

, at the same time.

Dividing his attention between a routine vehicle that failed to inspire him and a Gershwin-scored ballet that paid homage to his Impressionist idols was the sort of situation that would reemerge later in Minnelli’s career. To some extent, it was also the kind of psychological predicament that Vincente struggled with on a daily basis. Reality, like some colorless, uninspired screenplay, always seemed to be tugging him back from a place he’d much rather be—namely, wandering through his own mind, the ultimate MGM musical.

“MY FIRST DAY ON

An American in Paris

, I looked around and I thought, ‘Wow! This is a really good group,’” says dancer Marian Horosko, who appeared in the ballet:

An American in Paris

, I looked around and I thought, ‘Wow! This is a really good group,’” says dancer Marian Horosko, who appeared in the ballet:

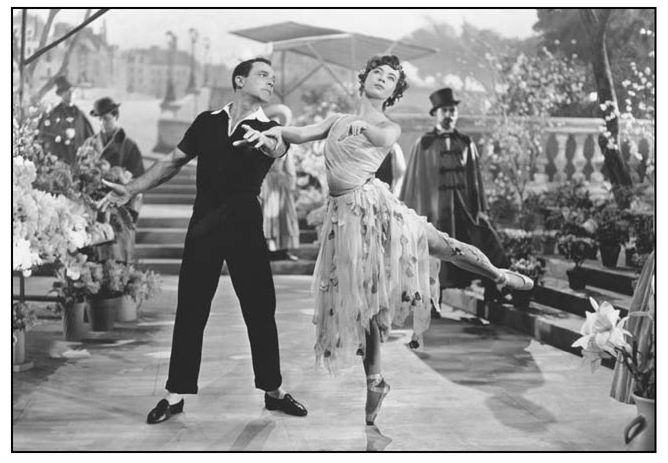

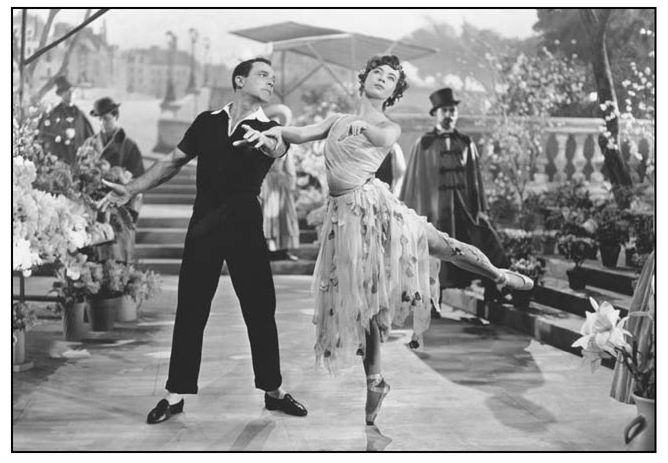

Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron in the ballet from

An American in Paris

. Minnelli decreed: “It has to be something to do with

emotions

, the time in his mind, the way he feels having just lost his girl, and a whole thing about Paris. . . . ” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

An American in Paris

. Minnelli decreed: “It has to be something to do with

emotions

, the time in his mind, the way he feels having just lost his girl, and a whole thing about Paris. . . . ” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

You could tell that this was not your cute little Hollywood number. . . . I remember Gene Kelly had a sweetness about him that you would just do whatever he wanted. He was your baby brother. He was jazzy and he had a good sense of humor and he sometimes looked concerned but not worried. The constant worrier was Vincente Minnelli. He always had a frown on his face and a twitch around his mouth and you wondered, “Does he hate us? . . . Are we all going to get fired?” Some of his physical tics were off-putting but if you could see through that, you found that he was a very intelligent man and his involvement was thorough. It was not just a director directing. He used fewer words than any director I’ve ever known except Balanchine. . . . He was always thinking and shaping things in his mind.

12

12

As the ballet was taking shape, it was easy to forget that there was another world going on beyond the one that had been carefully manufactured on the set, though every now and then reality would intrude. As Horosko recalls:

Underneath the joy and happiness and the good work, there was this undercurrent of unease with the House Un-American Activities. That whole business with the McCarthy investigations. You know those big gates that they have at

MGM? They would close the gates at lunch time and Louis B. Mayer would come out and say, “If you know anybody who’s not loyal to the United States, come to my office. We understand these things and just come and talk to us about it.” And I thought, “Oh, boy!” To me, that was pure Nazi stuff. I came back to New York fast enough.

13

MGM? They would close the gates at lunch time and Louis B. Mayer would come out and say, “If you know anybody who’s not loyal to the United States, come to my office. We understand these things and just come and talk to us about it.” And I thought, “Oh, boy!” To me, that was pure Nazi stuff. I came back to New York fast enough.

13

The ballet would include some of the most indelible imagery in the entire Minnelli canon. The long, slow dissolve from the Dufy-inspired Place de la Concorde to the Renoir-styled flower market (“Marché aux Fleurs”) at dawn is gracefully synched to Gershwin’s music. The shot of Kelly and Caron intertwined on the Greutert fountain as John Alton’s

fumata

cascades over them is undoubtedly one of the most unapologetically erotic moments in all of Minnelli. As Kelly and Caron jump up and down on the fountain during the euphoric climax, their exuberance is not only about finding one another but about willing such a beautiful moment into being. For Vincente, the sequence was both a daunting challenge and the realization of many fantasies—suddenly his cherished art-book images were vibrantly alive, as they had been for so many years in his mind.

fumata

cascades over them is undoubtedly one of the most unapologetically erotic moments in all of Minnelli. As Kelly and Caron jump up and down on the fountain during the euphoric climax, their exuberance is not only about finding one another but about willing such a beautiful moment into being. For Vincente, the sequence was both a daunting challenge and the realization of many fantasies—suddenly his cherished art-book images were vibrantly alive, as they had been for so many years in his mind.

As the ballet dominated the second half of the picture and extended its running time, a number of deletions were deemed necessary. Although it was Kelly’s favorite of his own numbers, “I’ve Got a Crush on You” was excised from the release print along with two Guetary solos, “Love Walked In” and “But Not for Me.” However, the most poignant cutting-room floor casualty belonged to Nina Foch.

“I had a wonderful scene at the end of the movie where I sat with Oscar Levant and I was complaining and crying about losing Gene,” Foch recalls. “I think it’s one of the best pieces of acting I’ve ever done. I’m just buzzing, about to be a weepy drunk, half-laughing, and suddenly up comes this truly lonely, lonely little girl whose daddy never loved her.” Milo’s big moment was to have taken place in the midst of the black and white ball and included a brilliant bit of improvisation when a piece of confetti tumbled into Foch’s champagne glass—she retrieved it and knocked it back as though it were a pill. “Everyone who had seen it talked to me about that scene,” remembers Foch. “I got a letter from Arthur Freed afterwards saying, ‘We’re sorry we cut that wonderful scene out. We all loved it, but it made Gene look bad.’”

14

14

Though studio insiders were already buzzing about how outstanding the picture was, one of the most important endorsements was phoned in from New York. “I’ve seen your little picture,” Judy told Vincente. “Not bad. Only a masterpiece.” And most of the critics would concur. “Brilliant is the word

for MGM’s

An American in Paris

,” raved the

New York Journal American

. “Here’s a musical that’s out of the very top of the top drawer. . . . Its direction by Vincente Minnelli sets and sustains a sparkling tempo.”

15

In

Compass

, Seymour Peck quipped, “Who knows, it may even put Paris on the map.”

for MGM’s

An American in Paris

,” raved the

New York Journal American

. “Here’s a musical that’s out of the very top of the top drawer. . . . Its direction by Vincente Minnelli sets and sustains a sparkling tempo.”

15

In

Compass

, Seymour Peck quipped, “Who knows, it may even put Paris on the map.”

MARCH 20, 1952. OSCAR NIGHT. Vincente’s “little picture” had been nominated for eight Academy Awards. Despite the fact that Arthur Freed was producing the 24th annual Academy Awards ceremony,

An American in Paris

seemed very much the dark horse in the Best Picture race as it was up against such dramatic heavyweights as

A Streetcar Named Desire

and

A Place in the Sun

. “There is a strange sort of reasoning in Hollywood that musicals are less worthy of Academy consideration than dramas,” Kelly told the press.

16

His point was underlined by the fact that the last musical to snare the top prize had been Metro’s

The Great Ziegfeld

in 1936.

An American in Paris

seemed very much the dark horse in the Best Picture race as it was up against such dramatic heavyweights as

A Streetcar Named Desire

and

A Place in the Sun

. “There is a strange sort of reasoning in Hollywood that musicals are less worthy of Academy consideration than dramas,” Kelly told the press.

16

His point was underlined by the fact that the last musical to snare the top prize had been Metro’s

The Great Ziegfeld

in 1936.

For the first time in his career, Minnelli was nominated as Best Director, an honor many in the industry felt had been deserved as far back as

Meet Me in St. Louis

. When the envelopes were opened,

An American in Paris

would not only prevail as Best Picture but collect six other Academy Awards. Arthur Freed would be honored with the prestigious Irving Thalberg Award, and Gene Kelly received an honorary Oscar “in appreciation of his versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, and specifically for his brilliant achievements in the art of choreography on film.” The film’s director, however, would go home empty-handed. “How could anyone vote for [

An American in Paris

] as Best Picture of the Year and not recognize Vincente’s obvious contribution?”

17

Saul Chaplin would ask, echoing the feelings of many who had observed how tirelessly Minnelli had worked.

Meet Me in St. Louis

. When the envelopes were opened,

An American in Paris

would not only prevail as Best Picture but collect six other Academy Awards. Arthur Freed would be honored with the prestigious Irving Thalberg Award, and Gene Kelly received an honorary Oscar “in appreciation of his versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, and specifically for his brilliant achievements in the art of choreography on film.” The film’s director, however, would go home empty-handed. “How could anyone vote for [

An American in Paris

] as Best Picture of the Year and not recognize Vincente’s obvious contribution?”

17

Saul Chaplin would ask, echoing the feelings of many who had observed how tirelessly Minnelli had worked.

Other books

Monkey on a Chain by Harlen Campbell

The Secret Life of a Dream Girl (Creative HeArts) by Tracy Deebs

Selected Stories by Katherine Mansfield

Black Keys (The Colorblind Trilogy #1) by Rose B. Mashal

Unshapely Things by Mark Del Franco

Digital Gold by Nathaniel Popper

PUCKED Up by Helena Hunting

Manhood: The Rise and Fall of the Penis by Mels van Driel