Marie Curie (8 page)

Authors: Kathleen Krull

Tags: #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology, #Science & Nature, #General, #Fiction

She was not to see Ève and Irène for almost a year. For a while, Marie recuperated at the home of an old friend in England. Hertha Ayrton was a scientist (studying, among other things, sand ripples), a nurse, and a militant supporter of women’s right to vote. Ayrton had nursed back to health other suffragettes who had carried out hunger strikes in prison; now she applied her ministrations to Marie.

Marie did return home. However, for almost two years, illness hindered her career. She had managed to attend the first Solvay Conference in 1911, sponsored by Ernest Solvay, a wealthy Belgian chemist. He gathered the top twenty-one physicists around the world to discuss the new concepts of Einstein and the German physicist Max Planck. Marie contributed to the lively discussion but made no presentations and left early.

The following year, she was too sick to attend the Solvay Conference. Its ongoing project was to finalize a standard measurement for the amount of radioactivity found in anything. A “standard” sample of radium was needed. From her sickbed, Marie made it known that she would help the project but only on her own terms. For instance, she wanted the standard piece of radium to be kept at

her

lab. She had discovered the element, after all.

Rutherford was brought in to mediate, and although he referred to her as “a rather difficult person to deal with,” he managed to bring her around. Although still harboring a protective, almost motherly attitude toward radium, she worked to establish the standard, then in 1913 dutifully handed over the necessary amount of radium in person to the committee. Kept in a safe at the Office of Weights and Measures in Sèvres, the radium was to be made available to five continents. The committee agreed to call the standard unit of measurement a “curie”—the name by which it is known to this day.

Paul Langevin quietly went back to his wife. Marie closed herself to the possibility of love and concentrated on getting the Radium Institute off the ground.

She was having great difficulty regaining her full health, when a new crisis made all her previous troubles seem small.

CHAPTER NINE

War Heroine

I

N JULY OF 1914, war broke out, first between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, then widening across Europe, eventually pulling in some twenty-five countries, including the United States. As the deadliest confrontation in history so far, the Great War interrupted Marie’s work. Science that wasn’t war-related was put on hold.

“Senseless” was Marie’s word for war: “It is hard to think that after so many centuries of development, the human race still doesn’t know how to resolve difficulties in any way except by violence.” But while condemning the notion of war, she was determined to help France however she could, possibly also hoping to repair her tarnished reputation. First she offered to donate her prize medals when France asked citizens to donate their gold and silver (the offer was refused).

Then she carried out a daring mission at great personal risk. In September of 1914, after Germany dropped three bombs on Paris, the French president moved the government headquarters outside of Paris to Bordeaux. He worried that if Paris was captured, the valuable radium would fall into German hands and be used somehow against France. He assigned Marie to transport all the radium in France to Bordeaux.

With each tube encased in lead, it was such a heavy suitcase that people wonder to this day how she carried it. A young soldier on the train shared a sandwich with her and asked if she was Marie Curie. She gave her usual denial, in part from her abhorrence of publicity but also for fear that other passengers might think she was a coward fleeing Paris.

From the start, the death tolls were staggering—obscenely so. By November 1914, there would be 310,000 dead, and 300,000 wounded soldiers in France. Scientific “progress” had created new weapons; the Germans were concocting deadly gases like mustard and chlorine, never used before in warfare. Marie’s friend and nurse Hertha Ayrton invented a fan to blow the gases out of trenches, and Marie, too, was galvanized to do something healing for French soldiers. “We must act,

act

,” she said, putting her research aside—and inspiring her daughter Irène, now seventeen, to join forces with her.

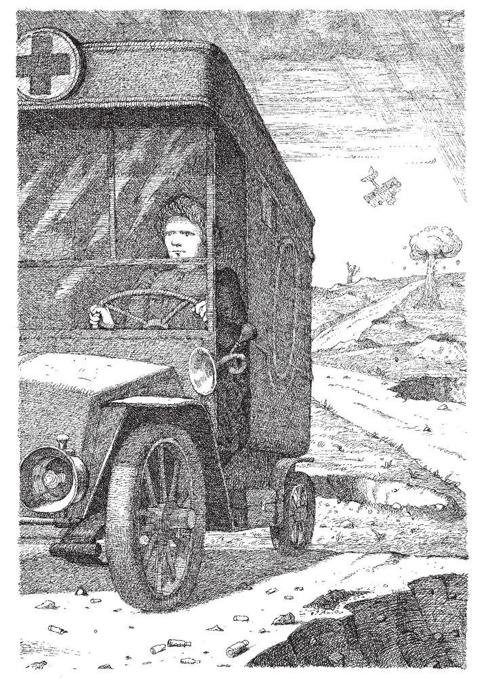

She learned that doctors on the battlefield had no X-ray equipment or technicians available to show where wounded soldiers had been hit by bullets and shrapnel. At the frontlines, wounded men were simply put in ambulances, “in a mixture of mud and blood,” as she described it, often dying on the way to a hospital. She knew X-rays could help save lives, so she invented a portable X-ray machine that could be transported to battlefields where it could immediately spot the location of a bullet, for example, inside a soldier’s body. Then she struggled for funding for an ambulance. Women drivers were still quite rare, but she got her license so she could drive to the front herself. But still she was not satisfied: she wanted to do more.

So next she commandeered all unused X-ray and automotive equipment in Paris. She assembled a fleet of cars (even limousines), installing X-ray machines inside that could be hooked up to a car battery if electricity wasn’t available. Keeping careful notebooks about everything, she trained 150 women technicians to go to the war front.

By 1916, she was director of the Red Cross Radiology Service, overseeing mobile X-ray units, which became known as “little curies.” She was unstoppable, unflappable, ingenious. Again proving herself to be her mother’s daughter, she even mastered the basics of car repair so she could take care of breakdowns on the field herself.

She was more than ably assisted by Irène, who was unusually intrepid for her age. Irène taught radiology classes to the military doctors and nurses, went to battle sites and performed X-rays herself, and drew diagrams showing exactly where to operate, sometimes arguing with doctors suspicious of her expertise. She described one doctor as “the enemy of the most elementary notions of geometry” while he was probing a patient’s wound. Neither Irène nor Marie bothered to take any precautions against excessive exposure to X-rays, the dangers of which were little known at the time.

Marie’s contributions to the war didn’t end with her fleet of X-ray units. In 1917, she also assisted Paul Langevin in inventing an early form of sonar that could capture ultrasonic vibrations—from deadly German submarines, for example.

Paint containing her discovery, radium, also proved useful to the military. Soldiers in the trenches were wearing a new type of watch, one that strapped onto their wrists. The soldiers needed to be able to tell time in the dark. Radium-based paint was used to make luminous numbers on the watch faces, as well as to highlight the dials of instruments on ships, planes, and tanks.

After four long years, World War I ended in November 1918. The joint forces of France, Italy, Great Britain, and the United States finally defeated Germany and its allies.

On the day victory was announced, Marie was in her lab. It was a day for celebration, and she rushed out to buy red, white, and blue material. With help, she sewed giant French flags to hang from the windows. She rejoiced further when news broke that for the first time in 123 years, Poland was liberated from foreign rule. An independent nation once again. Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the famous pianist and an old friend from her early Paris days, became free Poland’s first prime minister.

In France, the war had left one out of every six young men in the army dead—1,333,000. The figure would have been even higher had not more than a million X-ray procedures been performed on wounded soldiers. A medical technique in limited use before 1914 became standard practice by war’s end. American military doctors, before leaving for home, got training from Marie in X-ray procedures. After this, no surgeon would think of removing a bullet without precise knowledge of its location. This was due in large part to Marie Curie.

Now that it was peacetime, she did what she always did—she got back to work. The first order of business was writing

Radiology in War

. The beneficial use of X-rays was proof that pure science improved lives, although “only through peaceful means can we achieve an ideal society.”

Madame Curie was now at the high point of her fame. And as Einstein pointed out, “Marie Curie is, of all celebrated beings, the only one whom fame has not corrupted.” By now, she’d learned that fame could be useful, after all—a tool for fulfilling her humanitarian wish to “ease human suffering.”

The world “needs dreamers,” she said, and society should support them so that their lives “could be freely devoted to the service of scientific research.” She hoped to carry her words into action through the Radium Institute, her ultimate and long-postponed dream. After the war, in 1918, the buildings—two pavilions, with a rose garden in between—were opened at last.

CHAPTER TEN

Madame Curie

M

ARIE CURIE’S RADIUM Institute became one of the great research centers of the world. Its purpose was to study the chemistry of radioactive substances and to search for their medical applications. Through her institute Marie was providing shoulders on which the next generation of researchers could stand.

She ran the lab, keeping forty carefully selected researchers on staff, the best and brightest she could find (though talented women and Poles had a slight edge). Quietly but efficiently, researchers made breakthroughs.

A medical doctor, Claudius Regaud, headed the side of the Radium Institute devoted to medical advances, primarily in the treatment of cancer. Marie followed the work with great interest but didn’t contribute directly. Her discovery, radium, was now used in radium therapy, called curietherapy. doctors exposed patients to tiny amounts of radiation in the attempt to kill their tumors and cure them. The radium might be implanted under the patient’s skin, injected, or even swallowed! Early radiation sessions were very long, with patients given books to read and—unfortunately—cigarettes to smoke while waiting.

Between 1919 and 1934, under Marie’s serene guidance, the Institute published nearly five hundred books and papers, while its doctors treated over eight thousand patients. It was a small city, where she kept herself aware of every detail, multitasking her days away for a worthy cause. Marie, according to Regaud, “under a cold exterior and the utmost reserve . . . concealed in reality an abundance of delicate and generous feelings.”

Among her top priorities was the need to stockpile radium for use at the Institute as well as for scientists all over the world. Unfortunately, radium had become the most expensive substance in the world, approximately $3 million for a single ounce. As much as she hated wasting time with public relations, she did it. Publicity helped get money, and she played a part in exaggerating the highs and lows of her own career—the legend of Marie the martyr—in order to raise precious funds.

Americans were among her most devoted fans, entranced by the story of Marie. (Except for one chemist at Yale, who once called her “a plain darn fool . . . pathetic,” and later stated, “I feel sorry for the poor old girl.”) Newspapers had headlines like “Curie Cures Cancer!” and “The Greatest Woman in the World.” So to the United States Marie set sail, in 1921, with her two daughters. She did long to see the Grand Canyon and Niagara Falls, but the main purpose of the trip was fund-raising. She gave numerous college lectures, shook so many hands she had to wear a sling on her right arm, and collected honorary doctorates, medals, and membership in academies. The president of Harvard compared her to Isaac Newton, while

The New York Times

called her “a motherly-looking scientist in a plain black frock.” (Her best dress was still the same one she had worn to both Nobel ceremonies.)

The grand finale was an invitation to the White House, where President Warren G. Harding presented her with a gram of radium, almost doubling what she had. This gram was made possible by a $100,000 gift from the American Association of University Women. To women in America—who’d won the right to vote only a year earlier in 1920—she was a heroine, a role model. She was proof that women, even women with families, could become groundbreaking scientists.

Madame Curie’s radium stash was unrivaled until the appearance, after 1930, of accelerators that could produce radium in large quantities. Her hoard of radium made a decisive contribution to experiments undertaken for years afterward, especially those performed by Irène Curie, who was maturing into the superstar researcher at the Institute.

What remained was the still vexing question of how much exposure to radiation was too much. Marie was so determined that radium would benefit humanity that she tended to be blind to evidence that it might also harm. Usually she (as well as other scientists) maintained a certain state of denial about radiation sickness. But her own husband, Pierre, was possibly the first person to suffer from its effects. So sometimes she did admit its existence, but minimized its risks, viewing it as an annoyance, a hangnail instead of a death sentence. And so what if you had to put yourself in danger pursuing the noble cause of discovery? In her eyes, those who worried didn’t have a serious commitment to science.