Marie Curie (3 page)

Authors: Kathleen Krull

Tags: #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology, #Science & Nature, #General, #Fiction

Meanwhile, Bronia was reaching her own goal of becoming a doctor. In 1891, she was one of three women in a class of thousands to get her medical degree at the renowned Sorbonne, the central school at the University of Paris. She married another doctor, and with their thriving practice they could finally afford to bring Marie to Paris.

Now, after almost eight years, the escape hatch was lifted. So did Marie rush to buy a ticket and take the next train to France? No. At the last minute, Marie almost gave up her dream, her ambition. Casimir may have still been in the picture. Also her father needed her in Poland. Her vision slid out of focus: “I have lost hope of ever becoming anybody.” She was confused, torn: “On the other hand, my heart breaks when I think of ruining my abilities.”

Bronia set her younger sister straight. “You must make something of your life,” she insisted in a letter, convincing Marie to abide by their pact. Her father, though pained to see her go, didn’t hold her back.

In 1891, the twenty-four-year-old mostly self-taught scholar boarded the train to Paris. A thousand miles, three days, sitting all the while on a chair she had brought with her (fourth-class travel didn’t provide seats).

Honoring the pact was a turning point in her life.

Paris was . . . amazing, and so different from Poland. There was a glorious sense of freedom. Brand-new contraptions (automobiles) appeared on the streets. Lamps were lit with a new “magic fluid” (electricity). And such beauty—graceful, arching bridges over the Seine River that curled around the breath-taking Cathedral of Notre dame, monuments like the Panthéon (final resting place for French heroes), lavish theaters like the Opéra, and the newly built marvel called the Eiffel Tower, the tallest structure in the world. Multiple-story apartment buildings with lacy balconies of wrought iron overlooked wide avenues with fabulous bookshops, boutiques and cafés, people strolling about in the most fashionable clothes. Impressionists like Mary Cassatt and Claude Monet wowed the art world. daily newspapers mushroomed, fueling readers’ appetite for any new sensation. Over at the wild Moulin Rouge, the great actress Sarah Bernhardt appeared, as well as other performers, like a man who could fart the French national anthem, and racy can-can dancers memorialized by the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Marie, however, was not a big party girl. She had not come for a good time. She moved in with her sister and brother-in-law in the “Little Poland” area of Paris. It was an hour’s commute by horse-drawn bus to her real new home: the Sorbonne. She promptly enrolled in physical sciences, one of 23 women among 1,800 students. On registering for classes, she signed her name as Marie, the name she used ever after. With a bit of struggle, she became perfectly fluent in French (though she never lost her unmistakable Polish accent).

After a few months with her sister and brother-in-law, Marie struck out on her own, determined to take care of herself as cheaply as possible, without any help. She moved to the Latin Quarter, a funky area for students and artists, which was closer to school. She lived alone in a series of unheated attics—what were formerly servants’ rooms, often six flights up. In the winter, when the water in her washbasin would freeze solid, she slept with all her clothes piled on top of her. At night, after classes, experiments in the lab, and reading in the library, she ate a piece of chocolate with some bread, or once in a while an egg. One time she fainted on the street. Bronia brought her home and made her stubborn sister eat steak and potatoes.

Yet Marie always recalled this period with fondness, as “one of the best memories of my life.” She was happy: “It was like a new world open to me, the world of science which I was at last permitted to know in all liberty.”

Even in France, “No Girls Allowed” signs were still around. All the laws favored men—French women couldn’t vote, and young girls were educated separately in inferior schools. A popular book of the day discussed the “feeble-mindedness” of women. Female college students were so rare that the word in French (

étudiante

) was also slang for mistress of a male student. “Their study makes them ugly,” wrote one wit—they were considered a joke, attempting to change the laws of nature, probably not respectable.

All that mattered to ultra-serious Marie was that the Sorbonne allowed her to keep coming to classes. Her childhood in Poland had taught her how to fly under the radar. She didn’t dwell on how unusual she was, never talked about it, and always reported that other students treated her respectfully. Clearly not husband-hunting, she didn’t indulge in parties or café life. Now her only social interest was “serious conversations concerning scientific problems.”

In these post-Pasteur years, the French government was more generous with its financial support of the sciences. The Sorbonne had new lecture halls as big as theaters, and shiny, modern labs with state-of-the-art equipment. Marie’s teachers were the best men in science in France at the time.

Her physics professor, for example, was Gabriel Lippmann, who invented color photography a few years later (winning the 1908 Nobel Prize for it). Emile duclaux, a cutting-edge researcher and early advocate of Pasteur’s theories, was her biological chemistry professor. For math, Marie had Henri Poincaré, the greatest mathematician of his day. Her professors were impressed by Marie, and several helped her later on at various points in her career.

One textbook she had already mastered was the latest edition of Mendeleyev’s

Principles of Chemistry

. His periodic table was a system of ordering the elements according to what a single atom of the element was believed to weigh (its atomic mass). He went from the lightest (hydrogen, which became number 1) to the heaviest.

Among the sixty different elements known at the time, many had common characteristics in their chemical properties. Mendeleyev saw these subtle, shared similarities. And when he arranged the elements in horizontal rows of a certain length, he ended up with a chart where the vertical columns were of elements that all shared common characteristics.

He was so sure his pattern was correct that when arranging elements in rows, if the next heaviest known element didn’t conform to the pattern, Mendeleyev left a gap in the row and placed that particular element where its characteristics did fit the pattern. He understood that there must be a “missing” element, and at some point in the future, that new element would be discovered and slide into the gap.

In 1875, gallium was discovered, fitting in a gap under aluminum. In 1886, germanium was discovered, fitting in under silicon in a column that also included carbon, silicon, tin, and lead. As other new elements were discovered, Mendeleyev revised his table again and again.

The concept of the atom was nothing new. The Greek philosopher democritus in the fifth century B.C. had been the first to propose that nothing was smaller than the atom (from

atomos

, meaning “indivisible”).

Almost 2,500 years later, at the Sorbonne, the atom was still defined as “the smallest particle of matter.” End of story, no dispute. The nature of the atom was one of the few areas in science that was considered a closed case.

In other areas Marie had professors who said, “don’t trust what people teach you, and above all what

I

teach you.” In other words, think independently and test supposed “facts.” She was in heaven.

In 1893, she was one of only two women and hundreds of men pursuing a degree in physical sciences. She made herself ill over the upcoming final tests: “The nearer the examinations come the more I am afraid of not being ready.” She froze up during the difficult exam and was sure that she’d done badly. But when she went to hear the results of the exam, announced in order of merit, her name was read first. If the Sorbonne gave out gold medals, one would have been hers.

Now what? Something called the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry heard about Marie, this exceptional female student. It hired her to research the magnetic properties of various steels. The project involved work that demanded precision with much testing and graphing.

At the same time, she continued her studies, and in 1894 she earned a second degree, in mathematical sciences. did she come in first? No, Marie fell all the way to second place. Her plan at this point was to return to Poland and live with her father. With her two degrees she’d surely be in high demand as a teacher, able and willing to help her homeland.

It was in the spring of that year that she met Pierre Curie.

CHAPTER THREE

Magnetic Attraction

S

HE HAD HEARD his name before. Pierre Curie was semi-famous. Currently he was head of the lab at the brand-new Paris School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry. It was because Marie needed a bigger lab space of her own that mutual friends thought to introduce them.

Her very first impression was of a “dreamer absorbed in his reflections.” Also, “he seemed to me very young.” But in fact he was thirty-five, nine years older than Marie.

He was intense, shy, so quiet as a schoolboy that teachers dismissed him, saying he had a “slow mind.” His handwriting was terrible and he couldn’t spell. (Today Pierre Curie would likely be diagnosed with a learning disability, perhaps dyslexia.) So he was educated at home by tutors. His father and grandfather, both doctors, taught him how observations could be made about things invisible to the naked eye. At sixteen, he went into physics at the Sorbonne, then into chemistry at the School of Pharmacy, publishing his first article at twenty-one. With his brother Jacques, a professor of chemistry, he was making exciting discoveries about quartz crystals, which would later have applications for cell phones, Tv tubes, quartz watches, and microphones. Pierre and Jacques also invented an early version of an electrometer, an instrument that measured electric charges. Other physicists considered it quite cool and were using it.

Brilliant indeed, but Pierre was also known as an eccentric. He was humble to a fault, absentminded. Thanks to his homeschooling, he was not part of the establishment, and he preferred it this way. The school where he worked was not as prestigious as the Sorbonne, but it allowed him to pursue research in whatever he pleased, which was all he wanted of life. His one romance had ended unhappily (when the woman died); he still lived with his parents, under the assumption that a wife would only hinder his work.

“Women of genius are rare,” he stated. That was before he met Marie.

“We began a conversation,” she wrote later, “which soon became friendly.” Friendly talk about science. Pierre was completing his doctorate on the effect of heat on magnetic properties. He was one of the country’s experts on the laws of magnetism, and—what a coincidence—that happened to be Marie’s area of research as well. Perhaps they spoke about the problem he was currently working on—that at a certain temperature, a substance such as iron or nickel will lose its magnetism. This temperature point is still known as the Curie point in his honor.

His first gift to her was not chocolate or flowers. It was an autographed copy of his latest article, “On Symmetry in Physical Phenomena: Symmetry of an Electric Field and of a Magnetic Field.” She was smitten.

He, in turn, was impressed with her independence and her intelligence—she was even better at math than he was. She asked him to her attic room

with no chaperone present

, a shocking invitation. As there was no furniture, she simply pulled out a trunk for him to sit on, and he was charmed.

Idealists both, they wanted to devote their lives to science, though Marie still intended to return to Poland to serve her country. Each so independent, it took some dancing around and negotiating and a few misunderstandings before they realized that what drew them to each other was as important as their commitment to science. In one letter, he wrote that it would be “a fine thing” if they were together, “hypnotized by our dreams: your patriotic dream, our humanitarian dream, and our scientific dream.”

How could she resist?

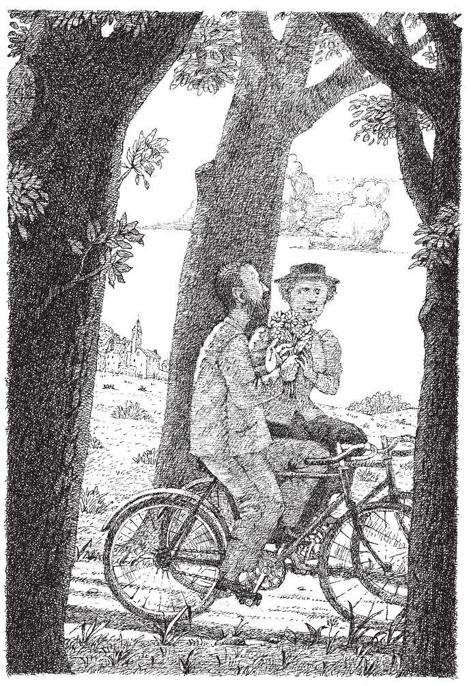

They married in July 1895, in a civil ceremony, with a reception in the garden of his parents’ home in the suburb of Sceaux. For wedding presents, they gave each other new modern bicycles, and their honeymoon was spent biking through scenic parts of France.

To begin married life, they settled into a small apartment on the Left Bank, filled with light and overlooking a garden. Their secondhand furniture included a dining-room table that doubled as a desk. Pierre supported them while Marie studied for her teaching certificate, took more physics classes, and did research on magnetism. He had zero problem with her continuing education—they were each other’s biggest cheerleaders. He always kept his favorite photo of her, labeled “the good little student,” in his vest pocket.

“We dreamed of living in the world quite removed from human beings,” he wrote. They spent their evenings reading scientific journals and discussing the articles. He didn’t pay attention to what he ate and often couldn’t remember whether he

had

eaten. Once in a while they went to the theater or to a brand-new sensation, the movies (pioneered by Frenchmen Auguste and Louis Lumière in 1896). They had little sense of fashion—he wore threadbare jackets and failed to keep his beard and mustache trimmed, while she wore cheap dresses in black or navy blue so as not to show stains from the lab. Their one luxury was fresh flowers in every room.