Map of a Nation (4 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

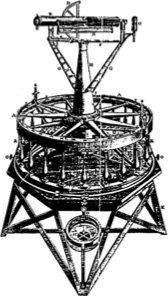

This book describes the circumstances that led to the creation of the First Series of Ordnance Survey maps. It is usually said that the Ordnance Survey was born in 1791, when the Master-General of the Army’s Board of Ordnance paid

£

373 14s for a high-quality surveying instrument and appointed the first three employees of a nationwide map. But in the

following

pages we will see how tricky it is to assign a decisive date to the start of that project. Arguably it really commenced in 1783, when a team of French astronomers approached the Royal Society to instigate a measurement between the observatories at Paris and Greenwich, a measurement that would form the backbone of the Ordnance Survey’s early work. The year 1766 is also a key moment in its gestation, when a far-sighted Scottish

surveyor

petitioned the King to set up ‘a General Military Map of England’. And it could even be suggested that the Ordnance Survey was first conceived twenty years earlier, from a map of Scotland that was conducted by that

same surveyor in the wake of Culloden. Recognising all these landmarks that paved the way to the Ordnance Survey’s completion of its First Series, this book reflects on what it was like to inhabit a nation that lacked a map of itself and how it felt to acquire that mirror.

At the same time as the Ordnance Survey was coming into being as a deeply loved and much-needed institution, the United Kingdom itself was also being formed through unions between England, Scotland and Ireland, and through the growth of national networks of travel, tourism and

communications

. Mile by mile, the Ordnance Survey painstakingly created an exquisite monochrome image of that new state, and the following pages describe how the changing face of the nation placed ever-increasing demands on the maps. But those requirements often led the map-makers astray from their principal focus, the creation of the First Series, so that – thanks to a wealth of fascinating digressions and distractions – it took

seventy

-nine years before those maps were completed in 1870. When that moment finally occurred, it was a landmark in Britain’s history, similar to the publication of the first edition of the

Oxford English Dictionary

in 1928. Both events gave the reading public deeper and wider insights into the physical and intellectual landscapes in which we live our lives.

For its readers today, the name ‘Ordnance Survey’ may conjure up a Betjemanesque image of cycle-touring or hiking through idyllic pockets of the British countryside, with only a map or guidebook for company. But as we shall see, its surveys emerged largely from a long history of

military

map-making

, in which that landscape was tramped over not by ramblers with a walking stick and a bag of sandwiches, but by redcoated soldiers.

1

During the Enlightenment, cartography became a symbol of the taxonomic intellect of the rational thinker, but philosophers were not the only ones to benefit.

2

Soldiers also became more ‘map-minded’ in this period, and the military was one of the principal crusaders in the improvement of British cartography over the course of the eighteenth century.

This book reveals a nation waking up, opening its eyes fully for the first time to the natural beauty, urban bustle and tantalising potential of its

landscape

. The ensuing chapters tell the stories of those who directed the Ordnance Survey’s early course: scientists, mathematicians, leaders, soldiers, walkers, artists and dreamers. They relate the hostility and intermittent friendship that characterised the fraught relationship between England and France over a century in which a prolonged and violent series of wars repeatedly set one against the other: an awkward backdrop, as we can

imagine

, for Anglo-French map-making collaborations. They describe the inanimate celebrities of the Ordnance Survey’s project – the most advanced, accurate, intricate measuring instruments that had ever existed; and the reactions of the maps’ first consumers, which ranged from loving adulation to protest. But above all, this book recounts one of the great British

adventure

stories: the heroic tale of making from scratch the first complete and truly accurate maps of a nation.

1

Survey

has a much wider range of meanings than

map

, referring to sweeping representations of the world in words as well as in images. But to avoid excessive repetition of the word ‘map’, I will use the two terms largely interchangeably, clearly differentiating them where necessary.

2

The word

cartography

refers to ‘the drawing of charts or maps’ and derives from the French

carte

, card or chart, and Greek

γραφία

, writing. Although it is a useful term that crops up

frequently

in this book, it is important to note that the word was only coined around 1859 and therefore was not used by the Ordnance Survey’s earliest map-makers and readers.

C

HAPTER

O

NE

O

N

29 J

UNE

1704, in a north-western suburb of Edinburgh, Mary Baird, the well-to-do wife of a successful merchant called Robert Watson, gave birth to her eleventh child: a son they called David. David Watson’s earliest years were spent in Muirhouse, which is now a sprawling housing estate to the north of Scotland’s capital, but was then a prosperous area populated by traders, where his father had recently purchased an enviable house with surrounding land. David was the baby of a large family, whose siblings ranged in age from two to fourteen, and around whom a host of affluent aunts and uncles clustered. But at the age of eight the young boy’s life underwent a dramatic upheaval: David’s father suddenly died. And in that same year his eldest sister Elizabeth, whose portrait shows her to have had kind but nervous eyes, a hesitant smile and luxuriant auburn hair, married into one of Scotland’s most influential families.

Elizabeth Watson’s suitor was a 27-year-old lawyer called Robert Dundas, heir to a dynasty whose command of the Scottish legal system in the

eighteenth

century has led it to be termed the ‘Dundas despotism’. His family played such significant roles in public life that their Victorian biographer concluded that ‘to describe, in full detail, the various transactions in which they took the leading part would be to write the history of Scotland during

the greater part of the eighteenth century’. Robert Dundas himself was a star in the legal firmament. He had been made Solicitor General of Scotland at a precociously young age, and rapidly attained the positions of Lord Advocate, Dean of the Faculty of Advocates and Lord President of the Court of Session. His reputation was immense: he was described as ‘one of the ablest lawyers this country ever produced’.

Gruff, with a tendency to irritability, Dundas was hardly the smooth and urbane lawyer one might expect. Physically he was not prepossessing. A friend described him as ‘ill-looking, with a large nose and small ferret eyes, round shoulders’ and ‘a harsh croaking voice’ with a robust Lowland Scottish accent. He was a man of unpredictable extremes, whose temper was said to be characterised by ‘heat’ and ‘impetuosity’ but matched with ‘

abundance

of tact’. He drank prodigiously – a bill for wine at his mansion over a nine-month period came to the equivalent of

£

11,000 – but he was still able to conduct his work with clarity and precision, even after ‘honouring Bacchus for so many hours’, as the novelist Walter Scott put it. And despite this erratic character, Dundas was highly respected. It was said that within three sentences his listener was invariably swayed by such ‘a torrent of good sense and clear reasoning, that made one totally forget the first impression’. Taking into account his inheritance of the stunning and capacious estate of Arniston on the fertile banks of the river Esk in Midlothian, Robert Dundas was an entirely desirable prospect for Elizabeth Watson.

At the time of her marriage, Elizabeth had just lost her father, and it is

possible

that her mother was also deceased by this point, as she and her new husband became something of surrogate parents to her eight-year-old brother David. His contact with the Dundas family would change the course of David Watson’s life. It was an exciting time: the atmosphere of Lowland Scotland was alive with optimism in the early eighteenth century. In 1707, an Act of Union had officially united Scotland and England into ‘Great Britain’ and, in the emerging ‘Age of Enlightenment’, the intellectual climate of this young nation was buzzing with a new intensity. The Dundases had played central roles in the Union and they considered themselves to be standard-bearers of the Scottish Enlightenment. His intimacy with this influential family would open up an array of opportunities to the young David Watson.

T

HE ONSET OF

an Age of Enlightenment in Britain was enormously helped by two events that had occurred in 1687 and 1688. The publication of Isaac Newton’s

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

(

Mathematical

Principles of Natural Philosophy

), and the ‘abdication’ of King James II of England, followed by the arrival of his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William as joint monarchs, were events that were both widely considered to demonstrate the potential of human powers of reason. Newton’s

Principia Mathematica

revealed that, despite its semblance of

arbitrariness

and confusion, the cosmos was really a unified system. And the ‘Glorious Revolution’ that was marked by James II’s departure set a new precedent for the relationship between the government and the Crown, founded on the rational principles that Britons deserved ‘the right to choose our own governors, to cashier them for misconduct, and to frame a

government

for ourselves’. Following these momentous occurrences, the philosophers of the British Enlightenment emphasised that science, politics, geography, art and literature should be guided by reason above all else. They were confident that powers of rationality could uncover the truth about the world. One of the key aspirations of Enlightenment thinkers was the creation of a vibrant ‘public sphere’ in which every member of the

populace

would feel free to ‘

Sapere aude!

’ – to dare to think for themselves.

The Enlightenment had important consequences for maps and

map-making

in Britain. A new ideal was dangled before surveyors: that cartography could be a language of reason, capable of creating an accurate image of the natural world. Enlightenment thinkers invested maps with the hope that the repeated observation and measurement of the landscape would build up an archive of knowledge that approached to perfect truth. The French

philosophes

Diderot and d’Alembert saw maps as images of the ordered, rational mind, and they compared their own

Encyclopédie

to ‘a kind of world map’ whose articles functioned like ‘individual, highly detailed maps’. The natural philosopher Bernard de Fontenelle described the

zeitgeist

of the Age of Enlightenment as an ‘

esprit géométrique

’. The twentieth-century Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges has encapsulated the

desire of thinkers in this period for ultimate ‘Exactitude in Science’ by

likening

it to the ultimately doomed objective to make ‘a Map of the Empire’ on the scale of one-to-one, whose ‘size was that of the Empire, and which

coincided

point for point with it.’