Map of a Nation (10 page)

Authors: Rachel Hewitt

The map-makers seem to have found surveying the Lowlands a delight compared with the Highlands. The scenery was flatter, lusher, densely

interlaced

with roads and punctuated with luxurious manicured estates. And the men were received politely, even enthusiastically, by the residents. Robert and Robin Dundas opened their family seat at Arniston to the Military Surveyors, and David Dundas repaid his extended family’s hospitality by mapping their fertile, elegant estate. The Dundases’ neighbours proved equally welcoming. The proprietor of the nearby estate of Penicuik was a man called Sir John Clerk, whose portraits show him to have had an alert gaze and a stern jaw offset by a quick readiness to smile. Clerk was an extraordinary polymath: a politician, lawyer, judge, patron of the arts,

occasional

natural philosopher, composer and a committed antiquarian. At his mansion, Clerk gathered around him the leading lights of the Scottish Enlightenment: the poet and painter Allan Ramsay, the archaeologist Alexander Gordon, the philosophers Adam Smith and David Hume, and figures such as William Robertson, John Home, Alexander Wedderburn, Alexander Carlyle, John MacGowan, William Wilkie, John Blair, James Hutton, William Falconer, Adam Ferguson, ‘and many others … whose superior taste and genius have since been displayed in elegant, useful works which have rendered their names immortal’.

The Hanoverian military had long been warmly received by the gentry of Lowland Scotland, who often welcomed the soldiers as a source of willing manual workers. In the 1740s one military engineer boasted to Robert Dundas that ‘it has often been in my power, during the time that the

Reg[imen]t has been in Scotland’, to oblige landowners ‘with Ditchers & other Artificers’, and the two duly struck a deal whereby a team of military engineers agreed to mend Arniston’s internal roads. But the social status of the Board of Ordnance’s employees extended from the working class right up to the aristocracy, and many were welcomed into Lowland society on more equal terms. For example, the extraordinary Adam family of architects worked in Scotland as Master Masons to the Board of Ordnance, repairing and building forts and barracks. They supplemented these military duties with lucrative commissions to design and construct Palladian mansions for the richest Scottish proprietors, such as Floors Castle in Roxburghshire, Hopetoun House in Linlithgowshire and the Dundases’ own mansion at Arniston. The Adams were great friends of Sir John Clerk and his son, who referred to William Adam in particular as ‘a man of distinguished genius, inventive enterprise and persevering application, attended with a graceful, independent and engaging address which was remarked to command

reverence

from his inferiors, respect from his equals and uncommon friendship and attachment from those of the highest rank’.

Clerk sought out the Military Surveyors during their mission to map the Lowlands. He employed their young draughtsman, Paul Sandby, as a private tutor in painting for his son, in whom Sandby succeeded in igniting a passion for art that stayed with him until the end of his long life. And Clerk

particularly

took to the reserved director of the survey, William Roy. Perhaps sparked by an early childhood visit to the site of a Roman encampment near Cleghorn in Lanarkshire, Roy harboured a fascination for antiquities. He was specifically interested in remnants of permanent or temporary army encampments dating from the Roman presence in Scotland between 55

BC

and

AD

410. A keen amateur antiquarian himself, Clerk promptly led the map-maker on a tour of his estate where he had recently found a Roman station, which was marked, Clerk explained, by ‘a tumulus, where several urns, filled with burnt bones, have been dug up’. Delighted by the discovery, Roy duly ‘pointed it out in his maps’.

In the years that followed, the influx of new personnel onto the Military Survey meant that Roy found more time to indulge his antiquarian foible. He felt that the ‘ordinary employments’ of a military map-maker, which involved

minute attention to the landscape, were ideally suited to serious examination of antiquities. Roy also believed that the relatively unchanged Scottish

landscape

provided a line of communication and sympathy between the military men of his own time and the Roman generals who had stalked that same territory 1500 years previously. ‘While the ranges of mountains, the long extended valleys, and remarkable rivers, continue the same,’ he wrote, ‘the reasons of war cannot essentially change.’ In Roy’s view, the military

map-maker

was the ideal antiquarian, able ‘to compare present things with past’ and ‘converse with the people of those remote times’. So he delegated the mapping of the Lowlands’ interior to his colleagues and reserved for himself the border lands between England and Scotland. While surveying this

territory

between 1752 and 1755, this gentle young man in his mid-twenties investigated a host of Roman encampments, and made minute charts of those at Chew Green, Liddle Moat and Castle-o’er. Roy became particularly fascinated by the way in which Scotland’s boundaries had shifted over time and how these changes were imprinted onto the land itself by the Antonine Wall (which ‘begin[s] at the Clyde, and end[s] at the Forth’) and Hadrian’s Wall (running between Newcastle upon Tyne and the Solway Firth).

William Roy’s obsession with Roman military antiquities in Scotland would last until the end of his life. Twenty years after it first gripped him, Roy became a prominent member of London’s Society of Antiquaries, and the recipient of heartfelt pleas from colleagues to write up his researches for publication. What began as a smattering of essays gradually expanded into a lavish book entitled the

Military Antiquities of the Romans in North Britain

. Roy adorned his text with his own meticulous surveys of Roman sites, including a particularly beautiful map of the encampment at Cleghorn. He prefaced the entire volume with a national survey that caused quite a stir on its first publication. The

Mappa Britanniae Septentrionalis

was a minutely detailed map of north Britain, based on information that Roy had collected during the Military Survey of Scotland. When the reading public got wind of the

existence

of such an accurate map of the whole Scottish nation, demand was so great that, despite having no plans yet for publication of the text, Roy was persuaded to engrave and publish the

Mappa

separately. Three years after his death, the Society of Antiquaries finally published Roy’s

Military Antiquities

as

a spectacular elephant folio, a fitting memorial to his achievements in the fields of military history and antiquarian research.

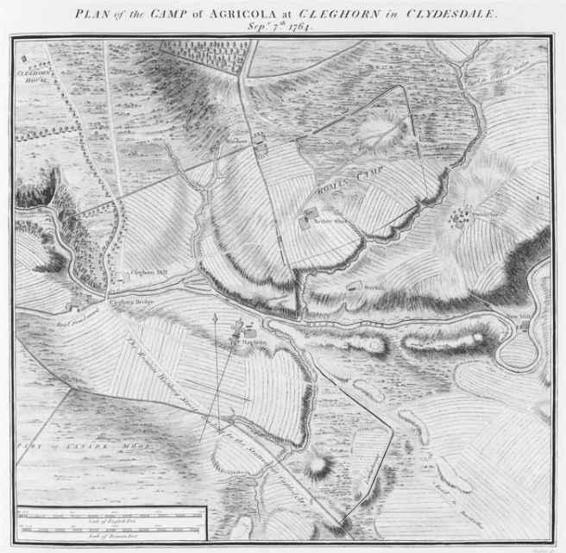

10. A sketch from William Roy’s

Military Antiquities of the Romans in North Britain,

1793, showing a ‘Plan of the Camp of Agricola at Cleghorn in Clydesdale’, not far from Roy’s birthplace near Carluke.

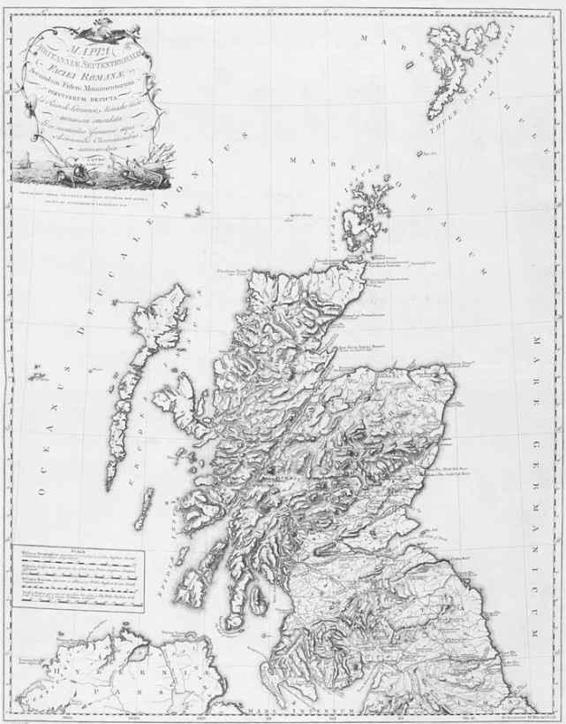

11. A map of the Scottish mainland from William Roy’s

Military Antiquities of the Romans in North Britain.

This incorporates measurements taken during the Military Survey of Scotland.

T

HE EXPANDED TEAM

of Military Surveyors swept through the Scottish Lowlands in three years. By 1755 they had made working drafts of maps of

the whole region, although they had not managed to produce finished ones. But by the late summer of that year, conflict on the Continent had become inevitable and the Board of Ordnance called the Military Survey’s personnel away from Scotland to employments required by the impending Seven Years War. The mapping project came to an end.

In the period between the Military Survey’s commencement in the summer of 1747 and its termination in 1755, Roy and his men had

produced

maps of varying degrees of completion of the entire Scottish mainland. The Military Surveyors proudly mounted their maps of the Highlands onto eighty-four brown linen rolls, of which twelve constituted the ‘fair plan’, and they prepared their Lowland maps on ten. These were later cut and reconstituted to make thirty-eight folding sheets which, when pieced together, form a complete map thirty feet high and twenty feet wide. As one witness aptly commented, it was ‘immense’. David Watson initially kept hold of the individual sheets, but at some point in the 1760s they were transferred to the King’s Library at Windsor. Finally the Military Survey became part of the ‘King’s Topographical Collection’, the title attributed by the British Library to the Topographical and Maritime Collections of King George III, a breathtaking array of some 50,000 atlases, maps, plans, prospects and views assembled through that monarch’s reign. Any reader of that public library can order sheets of this beautiful, nation-changing map to view in person. Anyone can spread out, across the Map Reading Room’s enormous tables, this window onto a lost landscape.

The Military Survey of Scotland, in its final state, is a vast, gorgeous bird’s-eye view of mid-eighteenth-century Scotland. One of its surveyors, Hugh Debbieg, described the project as ‘the greatest work of this sort ever performed by British subjects’ and one of ‘the fine[st] Representations of the Country … in the World’. From the cliffs of Cape Wrath in the most

north-westerly

point of Scotland to the windswept coastlines and castles of Aberdeenshire in the east; across the glens of Angus, Fife’s bays, the forests of Perthshire, and the rugged mountains and lochs that punctuate the Trossachs and the Western Highlands; to the burgeoning cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the Lothians’ damp and fertile parks, the ancient stone circles in Ayrshire, and the deserted beaches of Galloway; right down to the gently

undulating hills and plains of the Borders, the map-makers had drawn it all, in pen-and-ink and watercolour washes. An early witness of the survey noted that ‘the Mountains and Ground appear shaded in a capital style by the pencil of Mr Paul Sandby, subsequently so much celebrated as a Landscape Draughtsman. The outlines were drawn and other particulars were inserted under the care of General Watson by sundry assistants.’ And although the Military Survey of Scotland bore no legend to explain its ‘vocabulary of symbols’, the map was constructed in a language derived from contemporary Continental military surveying. Hedgerows were shown as lines of miniature trees. Enclosed fields were patches of green, sometimes containing scatterings of bushes. The roads over which Roy had trudged for eight years and six months were delineated by brown lines. Tilled land was represented by parallel hatching and rivers by turquoise streaks. Sand was denoted by stipple and moorland by infrequent patches of grass. Urban settlements consisted of loose grids and inhospitable mountains were

signified

by fierce strokes of brown-black paint, whose tone and direction indicated the shape and slope of the peaks. The Military Survey is a rare, delicate specimen of Enlightenment cartography that has been said to offer ‘a picture of Scotland on the eve of great changes’.

Wonderful as it is, the Military Survey is not a uniformly accurate image of the landscape. It was the product of a small team of young and

inexperienced

map-makers, and the eight years and six months it took to complete was ridiculously swift for such an enormous, varied area of country. There are wild discrepancies in the levels of detail and completion between

different

sheets of the map, probably due to the changing practices of individual surveyors. Scotland’s islands were completely omitted, the finished maps bore no information about longitude or latitude, and they failed to indicate the direction of magnetic or true north. More importantly, the map-makers’ method of ‘traverse surveying’ resulted in the proliferation of errors over large distances, and a comparison of the Military Survey with a modern Ordnance Survey map of Scotland reveals serious divergences. The eastern end of Loch Leven, for example, is positioned on the Military Survey a good twenty miles south of its actual location. William Roy later justified his map’s inaccuracies by explaining that it was ‘carried on with

instruments of the common, or even inferior kind, and the sum annually allowed for it [was] inadequate to the execution of so great a design in the best manner’. It was, Roy admitted, ‘rather to be considered as a magnificent military sketch, than a very accurate map of a country’.