Making a Point (8 page)

Authors: David Crystal

It was perhaps a little unfair to blame the teachers, who for the most part were simply doing what the writers of the best-selling grammars were telling them to do. But Sheridan was right to single out the grammarians, whose focus had largely been on the syntactically intricate sentences of the written language, with little reference to speech other than the most basic recommendations about pausing. Anyone who tried to read a text aloud using the phonetic equations of Murray

et al

. would never hold an audience for long.

However, the elocutionists couldn't stop the grammatical steamroller. It's clear from the way authors wrote during the eighteenth century that they increasingly felt complex sentences needed a correspondingly explicit punctuation, with every syntactically important element identified to avoid uncertainty over how to read a discourse. The punctuation

became heavier and heavier, as writers accepted the recommendations of the grammarians, and in cases of doubt added â like David Steel â extra marks.

The result can be illustrated by a sentence from the preface to Dr Johnson's

Dictionary

(1755):

It will sometimes be found, that the accent is placed by the authour quoted, on a different syllable from that marked in the alphabetical series; it is then to be understood, that custom has varied, or that the authour has, in my opinion, pronounced wrong.

It's easy to see what has happened: a comma is used to identify the main chunks of syntax that make up the whole, and a semicolon links two sentences that are felt to be closely related in meaning. Some writers or printers would have gone even further than that, such as by separating the adverbs and writing âIt will, sometimes, be found' or âit is, then, to be understood'. But a lightly punctuated version, such as the following, is something we don't see until the twentieth century:

It will sometimes be found that the accent is placed by the authour quoted on a different syllable from that marked in the alphabetical series. It is then to be understood that custom has varied or that the authour has in my opinion pronounced wrong.

If you feel this is underpunctuated you may add commas to suit your taste; but few modern readers would insert as many as we see in Johnson.

Grammarians and elocutionists may have had their differences, but they were united on one point: opposition to the printers, whose ânegligence' had been remarked on by Jonson, Sheridan, and others. Both groups were concerned

with establishing principles, and they didn't see much principle in the way the printers worked. It was time for a change. The printers had had their own way for too long.

Interlude: A punctuation heavyweight

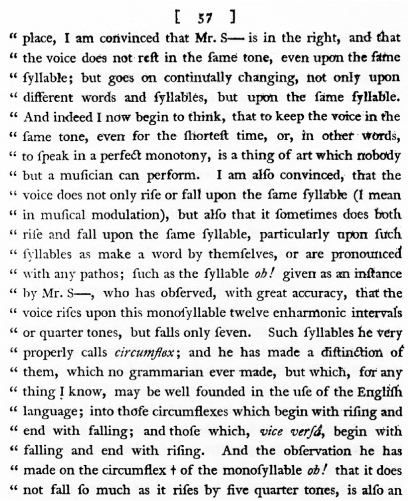

Joshua Steele's

An essay towards establishing the melody and measure of speech

(1775) is a typical example of the heavy punctuation encountered in eighteenth-century texts. This is an extract from a letter, seen as a quotation, and thus marked by opening inverted commas at the beginning of each line â a normal convention of the time. Only one line lacks a punctuation mark; line 6 has four commas. Even the page number is set off by brackets.

9

The printer's dilemma

I imagine the state of mind of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century printers was similar to Caxton's, 300 years before: âLo! what should a man in these days now write?' They were in a difficult position, as they had two diametrically opposed kinds of author to deal with. One kind â let's call them Jonsonians â were scrupulous about punctuation, and insisted on checking every mark for printing accuracy, getting very annoyed if a printer dared to change anything. The other kind â let's call them Wordsworthians â couldn't have cared less, and were extremely grateful to get any help they could.

I single out Wordsworth because, by his own admission, he was hopeless at punctuation and abdicated all responsibility for it. As he was preparing the second edition of the

Lyrical Ballads

, he wrote to the chemist Humphry Davy (28 July 1800) and asked him to check the text for punctuation:

You would greatly oblige me by looking over the enclosed poems, and correcting anything you find amiss in the punctuation, a business at which I am ashamed to say I am no adept.

He had never even met Davy! The suggestion had come from Coleridge. And not only does he ask this total stranger to correct his work, but later in the letter he asks Davy to send the corrected manuscript directly on to the printer, without referring back to him. Which bits of the end product's

punctuation are due to Davy, the printer, or the author we shall never know.

A roll-call of literary authors between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries would show them lining up under Jonson or Wordsworth. Among the Jonsonians is John Dryden, who in one of his letters (4 December 1697) complains to his publisher, Jacob Tonson, that âthe Printer is a beast, and understands nothing I can say to him of correcting the press', and in another insists that his work be printed âexactly after my Amendments: for a fault of that nature will disoblige me Eternally'. Although relationships later improved, he was not at all happy with Mr Tonson, whom he pilloried in an epigram (published in

Faction Displayed

, 1705):

With leering Looks, Bullfac'd, and Freckled fair,

With two left Legs, and Judas-colour'd Hair,

With Frowzy Pores, that taint the ambient Air.

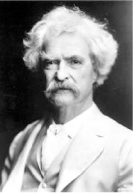

Printers beware, when dealing with satirical poets! Or, as we shall see later, novelists like Mark Twain.

Keats also took a keen interest in the way his publisher dealt with his copy. In a letter of 27 February 1818 to John Taylor, he writes:

Your alteration strikes me as being a great improvementâthe page looks much better. And now I will attend to the Punctuations you speak ofâthe comma should be at

soberly

, and in the other passage the comma should follow

quiet

. I am extremely indebted to you for this attention and also for your after admonitions.

And Tennyson asked his publisher Edward Moxon (letter of 13 October 1832) to âsend me every proof twice over. I should like the text to be as correct as possible.'

Among the Wordsworthians is Thomas Gray, who in an

undated letter in 1768 gives over eight pages of instructions to Foulis Press about how to print his poems, but adds: âplease to observe, that I am entirely unversed in the doctrine of

stops

, whoever therefore shall deign to correct them, will do me a friendly office.' And Byron writes to John Murray (26 August 1813) to ask: âDo you know any body who can

stopâI

mean

pointâcommas

, and so forth? for I am, I fear, a sad hand at your punctuation.' And in a P.S. to a later letter (15 November 1813) he adds: âDo attend to the punctuation: I can't, for I don't know a comma â at least where to place one.'

Printers obviously had the final responsibility of making a work look attractive, so that people would buy it. They knew that browsers in a bookshop â then as now â pick up a book and flick through the pages to see if it is for them. And among the many factors which influence the decision to buy are the layout of the text and the clarity of the writing, in both of which punctuation plays an important part. So it's unsurprising that they paid especial attention to this aspect of the copy. It was not just a matter of adding the occasional comma. There were major ambiguities that had to be sorted, such as when an author failed to use quotation marks consistently, so that it was impossible to identify who was saying what in a conversation. Charlotte Brontë, in the persona of C Bell, writes (24 September 1847) to her publisher Smith, Elder & Co about the proofs of

Jane Eyre

:

I have to thank you for punctuating the sheets before sending them to me as I found the task very puzzling â and besides I consider your mode of punctuation a great deal mo[re] correct and rational than my own.

The printers had to frequently correct her use of quotation marks and to insert colons, semicolons, and periods into

what was a very lightly punctuated and difficult-to-read manuscript. She wasn't atypical. It wasn't until the late nineteenth century that it became routine for authors to submit clean copy on sheets of the same size, writing on just one side of the paper, and avoiding the heavy self-corrections that can make a manuscript illegible.

The major printing manuals of the period all address the issue. John Smith's

Printer's Grammar

(1755) is mainly about the work of the compositor, and deals with the different fonts, letter sizes, differences between large and small capitals, and other technical matters. When he addresses the topic of pointing, he distinguishes two kinds of writer:

[some authors] point their Matter either very loosely or not at all: of which two evils, however, the last is the least; for in that case a Compositor has room left to point the Copy his own way; which, though it cannot be done without loss to him; yet it is not altogether of so much hinderance as being troubled with Copy which is pointed at random, and which stops the Compositor in the career of his business more than if not pointed at all.

Writers, Smith finds, are typically lax:

most Authors expect the Printer to spell, point, and digest their Copy, that it may be intelligible and significant to the Reader.

He has no time for the grammarians, whom he accuses of artifice in the way they introduce rules (I imagine he is thinking of such things as the pause equations mentioned in

Chapter 8

) that have no basis in real life:

When we compare the rules which very able Grammarians have laid down about Pointing, the difference is not very

material; and it appears, that it is only a maxim with humourous Pedants, to make a clamour about the quality of a Point; who would even make an Erratum of a Comma which they fancy to bear the pause of a Semicolon, were the Printer to give way to such pretended accuracies. Hence we find some of these high-pointing Gentlemen propose to increase the number of Points now in use.

And he adds that printers must take a firm stand when dealing with one of these high-pointing gentlemen.

Smith also draws attention to the increasingly important role of correctors â we would call them copy-editors today â whose role is to review manuscripts to avoid compositors having to make changes at proof stage. By the time Charles Stower wrote another

Printer's Grammar

(1808) â a much-used authority in the early nineteenth century â the balance of power had changed within the printing-house: the primary responsibility for accuracy of copy was now in the hands of the corrector, who âshould make it a rule never to trust a compositor in any matter of the slightest importance â they are the most

erring

set of men in the universe'. The corrector had considerable editorial power in those days. It is his responsibility, says Stower, to eliminate from a manuscript any anomalies âof no real signification; such as far-fetched spellings of words, changing and thrusting in points, capitals, or any thing else that has nothing but fancy and humour for its authority and foundation'.

It was the same in the USA. By the end of the nineteenth century, the professionals employed by a publisher had grown to include proof-readers as well as copy-editors, and their role is highlighted by Thomas Mackellar in his influential

The American Printer: A Manual of Typography

(1866):

The world is little aware how greatly many authors are

indebted to a competent proof-reader for not only reforming their spelling and punctuation, but for valuable suggestions in regard to style, language, and grammar,âthus rectifying faults which would have rendered them fair game for the petulant critic.

Today, a single professional body combines both these editorial tasks: in the UK, it is the Society for Editors and Proofreaders.

None of this stopped petulant criticism being directed at publishers, when it came to punctuation. Henry Alford, Dean of Canterbury and author of

The Queen's English

(1864), has little to say about the subject, but when he does address it (in his section 124) he pulls no punches:

I remember when I was young in printing, once correcting the punctuation of a proof-sheet, and complaining of the liberties which had been taken with my manuscript. The publisher quietly answered me, that

punctuation was always left to the compositors

. And a precious mess they make of it.

What sort of thing did they do? He goes on:

The great enemies to understanding anything printed in our language are the

commas

. And these are inserted by the compositors, without the slightest compunction, on every possible occasion.

He is particularly angered by commas being used on either side of adverbs such as

too

or

also

(he is no supporter of Murray here) or separating adjectives in such phrases as

a nice young man

. He recalls a printer inserting a comma after the first word in

However true this may be

. And he blames printers for the excessive use of ânotes of admiration' (i.e. exclamation marks):

These

shrieks

, as they have been called, are scattered up and down the page by the compositors without mercy.

He recommends writers to use as few as possible.

However, on the whole during the nineteenth century there are signs of a growing rapprochement between grammarians and printers. We see the influence of printers in the content of some grammars; and we see printers taking more serious note of what grammarians have had to say.

Interlude: Strong language

Mark Twain is famous for his long-running battle with printers and correctors.

In 1889:

Yesterday Mr. Hall wrote that the printer's proof-reader was improving my punctuation for me, & I telegraphed orders to have him shot without giving him time to pray.

In 1893:

In the first place God made idiots. This was for practice. Then he made proof-readers.

And in 1898, in a letter to his publisher Chatto & Windus dated 25 July 1897:

I give it up. These printers pay no attention to my punctuation. Nine-tenths of the labor & vexation put upon me by Messrs. Spottiswoode & Co consists in annihilating their ignorant & purposeless punctuation &

restoring

my own.This latest batch, beginning with page 145 & running to page 192 starts out like all that went before it â with my punctuation ignored & their insanities substituted for it. I have read two pages of it â I can't stand any more. If they will restore my punctuation themselves &

then

send the purified pages to me I will read it for errors of grammar & construction â that is enough to require of an author who writes as legible a hand as I do, & who knows more about punctuation in two minutes than any damned bastard of a proof-reader can learn in two centuries.