Making a Point (11 page)

Authors: David Crystal

At least, when you're alive, you can make your own case to the publisher about preserving your desired punctuation. But what happens after you're dead? A different character now joins the company of punctuation-deciders listed in

Chapter 10

: the literary editor, ready to make fresh semantic and pragmatic decisions.

Interlude: Punctuation minimalism

The impression of unsophisticated innocence in NoViolet Bulawayo's story

We Need New Names

(2013) is well conveyed by the absence of quotation marks. The child narrator, from Africa but now living in America, describes how she met a woman at a wedding (the extract is from

Chapter 12

):

Can you just say something in your language? she says. I laugh a small laugh, because what do you say to that? But the woman is fixing me with this expectant stare, which means she is not playing, so I say:

I don't know, what do you want me to say?

Well, anything, really.

I let out an inward sigh because this is so stupid, but I remember to keep my face smiling. I say one word,

sa-li-bona-ni

, and I say it slowly so she doesn't ask me to repeat it. She doesn't.Isn't that beautiful, she says. Now she's looking at me like I'm a wonder, like I just made magic happen.

What language is that? she says. I tell her, and she tells me it's beautiful, again, and I tell her thank you. Then she asks me what country I'm from and I tell her.

It's beautiful over there, isn't it? she says. I nod even though I don't know why I'm nodding. I just do. To this lady, maybe everything is beautiful.

12

Interfering with Jane Austen

This is the opening sentence of Jane Austen's

Persuasion

(1818):

Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch Hall, in Somersetshire, was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any book but the Baronetage; there he found occupation for an idle hour, and consolation in a distressed one; there his faculties were roused into admiration and respect, by contemplating the limited remnant of the earliest patents; there any unwelcome sensations, arising from domestic affairs changed naturally into pity and contempt as he turned over the almost endless creations of the last century; and there, if every other leaf were powerless, he could read his own history with an interest which never failed.

Readers have long admired the balanced and elegant character of this sentence, with its three

there

-constructions building up a rhetorical peak, subtly linked by semicolons. But the punctuation is almost certainly spurious. That's not how she wrote at all.

We know this thanks to a splendid project, led by Professor Kathryn Sutherland of the University of Oxford, which has collated all the extant handwritten fiction manuscripts of Jane Austen in digital form. You can see them online at the appropriately named <

www.janeausten.ac.uk

>. There isn't very much, as all the original manuscripts of the novels were

destroyed after the books were printed â routine practice in an age long before author's holographs came to be valued in the way they are today. But what survives gives us a remarkable insight into her way of writing. And it is a goldmine for punctuation enthusiasts.

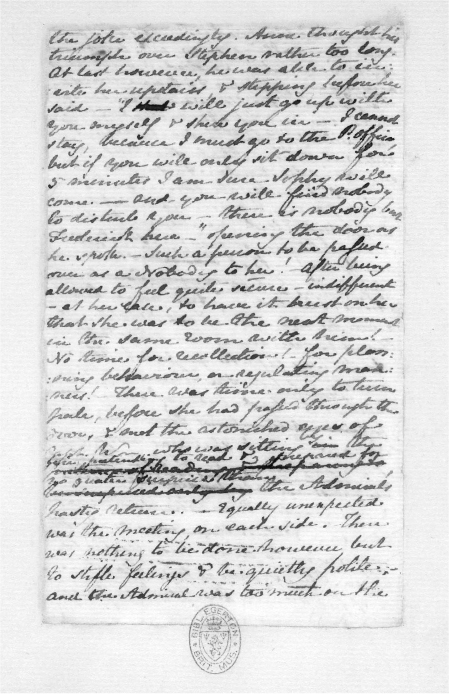

Page 4 of the rejected

Chapter 10

of

Persuasion

. It is written in brown iron-gall ink â a medium used by most English writers from the Middle Ages until the twentieth century. The quoted extract begins at line 3

.

Here's a short extract from

Persuasion

, from one of two chapters (page 4 of

Chapter 10

) which are the only surviving examples in Austen's handwriting of a novel that was completed for publication. If you know the book well, you won't recognize the text because these chapters were replaced in the published version. She changed the ending â and fortunately the unrevised text was never destroyed.

At last however, he was able to in:

:vite her upstairs, & stepping before her

said â “I

shall

will just go up withyou myself & shew you in â I cannot

stay, because I must go to the P. office,

5

but if you will only sit down for

5 minutes I am sure Sophy will

come. âââ and you will find nobody

to disturb you â there is nobody but

Frederick here â” opening the door as

10

he spoke. â Such a person to be paÅ¿sed

over as a Nobody to her! â After being

allowed to feel quite secure â indifferent

âat her ease, to have it burst on her

that she was to be the next moment

15

in the same room with him! â

No time for recollection! â for plan:

:ning behaviour, or regulating man:

:ners! â There was time only to turn

pale, â¦

I've chosen an extract where there is hardly any crossing-out, so that the style can be more easily seen. There are several interesting punctuation features. Word-breaks at the end of a line aren't signalled by hyphens, but by two colons â one at the end of the first line and the other at the beginning of the next (a throwback to the ancient tradition described in

Chapter 3

). Frequent exclamation marks convey the character's excitement. And above all, there are the dashes â a notable characteristic of Austen's style.

Handwriting does many things that print cannot do. The spatial relation of lines to each other can alter dramatically. Letter-sizes can vary enormously in a way that the contrast between upper-case and lower-case cannot capture. And if a dash is there to represent a pause, then the length of the dash tells us something that is lost when all dashes are reduced to a single piece of type in print. Look at the long dash in line 8, for example. Why such length? Read on in the novel. It anticipates âopening the door as he spoke'.

You won't see many dashes in the published book. We'd expect a publisher to do a certain amount of polishing, such as removing handwritten abbreviations (& vs

and

), correcting spelling mistakes (

recieve

), and ensuring house-style consistency (

judgment

vs

judgement

); but what Austen's editor did was far more radical. As Sutherland points out in

Jane Austen's Textual Lives

(2005), the manuscripts were normalized either by an editor at her publisher's (John Murray) or by a corrector in the printing-house. New paragraphing is introduced. Sentence construction is changed to follow prescriptive norms. Gone are her rhetorical dashes and her use of initial capitals on common nouns. And there is a huge amount of repunctuation, as seen in Sutherland's comparison of a section of manuscript in Austen's hand and the final text as it was printed.

Mrs. Clay's affections had overpowered her Interest, & she had sacrificed for the Young Man's sake, the possibility of scheming longer for Sir Walter;--she has Abilities however as well as Affections, and it is now a doubtful point whether his cunning or hers may finally carry the day, whether, after preventing her from being the wife of Sir Walter, he may not be wheedled & caressed at last into making her the wife of Sir William.--- | Mrs. Clay's affections had overpowered her interest, and she had sacrificed, for the young man's sake, the possibility of scheming longer for Sir Walter. She has abilities, however, as well as affections; and it is now a doubtful point whether his cunning, or hers, may finally carry the day; whether, after preventing her from being the wife of Sir Walter, he may not be wheedled and caressed at last into making her the wife of Sir William. |

Whoever corrected this is clearly under the influence of the heavy punctuational style recommended by the nineteenth-century grammarians I described in

Chapter 8

. And, as Sutherland points out, the process continued into the twentieth century, with subsequent editions reflecting later prescriptive preferences. For example, R W Chapman, whose five-volume edition appeared in 1923, considered the novels âunder-punctuated'. Sutherland reports an instance when Chapman asked the

Oxford English Dictionary

editor Henry Bradley for advice about how to punctuate the phrase âa quick looking girl' (describing Susan Price in

Mansfield Park

). Should he use a comma or a hyphen? Bradley's response (a letter of 14 February 1922) is illuminating: do neither.

Your alternatives of comma and hyphen imply different constructions, and I am not quite sure which is right, or whether the author may not have felt the collocation as

something between the two ⦠is it not possible that if we demand that it

must

be either comma or hyphen, we shall be insisting on a precision of grammatical analysis which punctuation has rendered instructive to readers of today, but which

c

1800 only a grammarian would be capable of?

Chapman let Austen's version stand in this instance; but in many other cases he implemented a policy, following the tradition going back to Lindley Murray, that punctuation exists to foster grammatical precision. And Sutherland concludes:

he prepared a text which actively and misguidedly promoted Austen's twentieth-century reputation as a conformant and prim stylistician.

The issues now go well beyond the linguistic, and raise fundamental questions about the role of editorial intervention in literature, and what exactly we are studying when we analyse the linguistic choices encountered in a text. Austen is not an isolated case. Many other authors have had their punctuation emended in a similar way.

In the case of Daniel Defoe's

Robinson Crusoe

, we have an even more complex situation, as several printers were involved, and there is no surviving author's manuscript. Defoe's publisher, William Taylor, farmed the manuscript out to a printer, Henry Parker, and the first edition appeared on 25 April 1719. Demand was so great that a second edition was required, and this was set in a hurry by three different printers, appearing two weeks later. A month later, there were two further editions set by the same three printers, and two more in August set by Parker alone. The textual variations introduced by the printers are an editorial nightmare for anyone trying to establish a version that comes closest to what Defoe intended. And variations in punctuation, according to Evan

R Davies, the editor of the Broadview 2010 edition, are most frequent of all. He writes:

To a reader accustomed to twenty-first grammatical conventions, the first edition of Robinson Crusoe can seem hopelessly mispunctuated, replete with fragmented clauses, run-on sentences, capricious commas.

He illustrates with a short comparison:

1st edition | 6th edition |

I consulted several Things in my Situation which I found would be proper for me, 1st. Health, and fresh Water I just now mention'd, 2dly. Shelter from the Heat of the Sun, 3dly. Security from ravenous Creatures, whether Men or Beasts, ⦠| I consulted several Things in my Situation which I found would be proper for me, 1st. Health, and fresh Water I just now mention'd. 2ndly, Shelter from the Heat of the Sun. 3dly, Security from ravenous Creatures, whether Man or Beast. ⦠|

Apart from the lexical changes (such as

Men

to

Man

), we see a grammatical punctuation replacing the rhetorical style. However, there is nothing âcapricious' about it. Both versions are systematic, but the later edition shows the clear influence of a printer wishing to make a text conform to the rules as laid down in the grammars of the time.

Those who have edited the few surviving manuscripts in Defoe's hand have noted a highly individual style, with idiosyncratic abbreviations and little punctuation. Davies generally keeps the punctuation of the first edition except where âthe meaning of the prose is seriously undermined', in which case he uses the punctuation of later editions. And, crucially, he gives a list of these changes â an eminently desirable practice that ought to be followed universally. For example, on p. 51, we read:

in an ill Hour, God knows, on the first of

September

1651 I went on Board a Ship bound for

London

;

We learn that the first edition has a period after âknows'. Nobody would disagree with the decision in this case. But the few instances where there is clearly an error are far outnumbered by the hundreds of instances where any emendation would be a matter of stylistic choice.

Modern editions have continued to make the punctuation conform to modern standards, as with Austen, so that the present-day reader encounters a text that is orthographically familiar. But ease of reading is gained at the expense of a distancing from Defoe's style â and in this case, from the character of the narrator, Crusoe. As Davies concludes:

Whether by accident or by art, Defoe created a text that matches its protagonist: neither Strunk nor White, but sprawling, rambling, and discursive.

William Strunk Jr and E B White are the authors of a good-usage manual, originally published in 1919 â the equivalent, to American readers, of Fowler in Britain.

Novelists who use as little punctuation as possible do so in an interesting way. They omit the features that were later arriving in the history of English orthography, as described in

Chapter 6

, such as quotation marks, semicolons, and apostrophes. They don't usually (James Joyce is an exception) mess about with the oldest features, such as periods and paragraphs. The same applies to poets whose punctuation is highly idiosyncratic: there may be variation in the use of one kind of feature (such as the use of dashes), but there is respect for others, such as stanza separation and the identity of the poetic line. All of this suggests that writers manipulate some features of orthography more readily than others.

This is indeed the case. As in any system, some features of punctuation have a critical role: the system would collapse if they were not there. Other features are less important: if they were missing, the written language would survive. We see this selectivity in practice in writers like Cormac McCarthy, as well as in the distinctive markings observed in the oldest English manuscripts. And from it we reach a conclusion of major significance for anyone involved in teaching or learning about punctuation: some marks are more important than others. The system, in a word, is hierarchical.

Interlude: Another case: Emily Dickinson

In the case of Emily Dickinson, we do have manuscripts, also written in a distinctively punctuated personal style, and this has caused not a little anxiety among some editors. For example, in the Random House 2000 edition of her

Selected Poems

, there is a Note on the Text as follows:

Dickinson wrote her poems in an eccentric longhand which featured the capitalization of substantive nouns and the use of the dash as a form of all-purpose punctuation. ⦠In order to make the poems more accessible to the eye of the modern reader, the oddities of punctuation and capitalization have been regularized in this edition.

The result can be illustrated by comparing two poems:

No. 113 in | No. 2 in |

Our share of night to bear â | Our share of night to bear, |

Our share of morning â | Our share of morning, |

Our blank in bliss to fill | Our blank in bliss to fill, |

Our blank in scorning â | Our blank in scorning. |

Here a star, and there a star, | Here a star, and there a star, |

Some lose their way! | Some lose their way. |

Here a mist, and there a mist, | Here a mist, and there a mist, |

Afterwards â Day! | Afterwards â day! |

Is the regularized version really âmore accessible'? And are we really reading Emily Dickinson in the 2000 edition? Not to my mind.