Machine Of Death (26 page)

Authors: David Malki,Mathew Bennardo,Ryan North

Tags: #Humor, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Horror, #Adult, #Dystopia, #Collections, #Philosophy

“Dad—”

“I

never

had heart problems,” Dad cried, suddenly strong, fidgeting to get an elbow underneath himself. James leaned over, but Dad struggled, righting himself on the couch. “I never had any heart problems whatsoever. Until that crook gave me those pills. And now look at me. Now look at me.”

“That’s why you have to take them. Yeah, call him a crook, maybe he is—but your heart will get worse unless you take the pills, and there’s nothing you can do about that.”

“Nothing I can do,” Dad said, shaking his head, trying to laugh, but it came out a choke. He eased himself back down onto the couch. “Nothing I can do until it wrecks my lungs, my kidneys, right? Same old story. Nothing I can do.”

James handed him the glass of water, rattling the pills in his hand, but Dad didn’t take it.

“At least I know this heart won’t kill me,” Dad said. “Whatever that mickeymouse box is good for, at least the heart won’t kill me.”

“That’s not necessarily true,” James said. “It—it’s kind of vague, I think.”

Dad looked at him, chewing his words, forcing them out. “So what, then? Every day I wake up it’s worse. I can’t talk, I can’t swallow! Now you want me to take pills so I can’t breathe, I can’t take a piss? Isn’t this bad enough?”

“Okay, Dad,” James said, setting the glass on the coffee table hard enough that it sloshed onto the magazines. “Go and see that kid, Tim, then. Go and see him, is that going to make you feel better?”

“At least

he

has some hope for me,” Dad said, and James bit his lip.

Tim’s house was one-half of a duplex on Brightwood Avenue, a wrongly-named street in a part of town without sidewalks. Brown front lawns ran straight into the cracked asphalt of the road, or at least they would if they were visible: Cars choked the sides of the road, and Mom had to park a block and a half away.

The people at Tim’s were sadder than at Dr. Eli’s, and some were sicker. Tim’s mother welcomed everyone inside with polite, weak handshakes. James stood in the corner, trying to shuffle as close to the wall as possible, so that everyone had room to sit.

The air was fogged with incense and something that sounded like Enya being played on a cheap boombox. Everyone kept quietly to themselves, occasionally shuffling one family at a time down a narrow hallway. The CD was on its second repeat when Tim’s mother called James’ parents to Tim’s bedroom.

Tim’s bed had Snoopy sheets on it, and model spaceships dangled from the ceiling, but there were no video games, no books, no other toys that would suggest that a child lived here. Tim sat cross-legged on his bed, thin and tired in the dimness of a single overhead lamp, and James almost gagged on the incense as he walked through the door.

He and Mom helped Dad to sit on a mound of pillows, then sat beside him. Tim was quiet, praying perhaps, his eyes closed, and he sat that way for some time before Dad started to moan loudly with discomfort.

“Thank you for coming back,” Tim said softly, and when he opened his eyes and saw James he froze for a moment, looking caught, looking terrified. Then he recovered, and extended his hands; Mom took one, and James, with some reluctance, the other, warm and wet. They both took Dad’s hands.

“Do you believe that you have the power to be healed,” Tim said. Dad said nothing until Mom nudged him, and even then he just murmured.

“Do you believe in the power that God has given to every man of his creation,” Tim said, louder, and Dad said, “Yes.”

“Do you believe that the power within you is strong enough to move mountains, because it is from God,” Tim said, his voice strong now, and Dad said, “Yes,” and Mom moaned.

“Remember to keep the flame of faith strong, for there is nothing I can do for you if you do not believe,” Tim said, softer now, and handed Mom’s hand and James’ hand to each other. He rose to his knees on the bed, his eyes closed, and started to flex his hands, as if preparing to play the piano, breathing sharply, quickly.

“It is your belief that allows the power to grow,” Tim said, “and opens a channel for me to reach into you.”

James watched his father closely, watching his head bob heavily on his neck as he slumped more deeply into the pillows. Tim’s hands moved deftly around one another, tracing intricate patterns that might have been tying bows with string, and Dad coughed and made a noise and spoke in syllables but not words.

After ten minutes of this Dad was not healed, but it was time to bring in the next family, so James helped his parents to their feet and nodded to Tim’s mother with a tight smile and concentrated on helping Dad into the car before he said anything.

“I think that kid is dangerous,” he finally said.

They drove home in silence. Dad was sleeping downstairs now, on the pull-out couch bed, and James helped him out of his shoes and socks. His feet were swollen, but his legs were as thin as James’ arms. James lifted Dad’s feet onto the bed and covered them with the blanket.

“How you doing,” he said to his father, because he had so much to say but didn’t know how to say any of it.

“What should I say,” Dad said. “Should I lie?”

James asked his mother not to go back to Tim’s.

“What exactly are you afraid of?” Mom said, brushing her hair in the darkness of her bedroom, as James leaned on the full-length mirror behind her. “That he’ll get better? That he’ll

feel

better, if nothing else? Like he’s trying to

do

something, instead of sitting around the house feeling awful, waiting—waiting to—waiting around?”

“I’m afraid he’ll think it’s his fault,” James said, and his mother stopped brushing.

When she didn’t say anything he spoke again. “I’m afraid he’ll feel like he didn’t believe enough. Like if only he could have more faith, or something, like if only he’d tried harder then Tim could heal him, and it’s

his

fault if he doesn’t get better.”

“I don’t think that,” Mom said, putting the brush away.

“I know, but does he?” James followed her down the hall, where she took a towel from the hall cupboard.

“I don’t think so.”

“How do you know?”

She whirled and faced him, and her voice was strong but he saw that her eyes were very wet. “Because I know him,” she said, and walked back to her room and closed the door and he heard the water come on in the shower.

“So do I,” he said.

“Bless this food to the nourishment of our bodies,” Dad said, slowly, “and thank You for all the blessings You give us. And I believe that You have the power to heal me, if it is Your will, and I ask that I be allowed to continue in Your service.”

They sat on the back porch, the sun a red ball on the horizon.

“I guess this is the end of my rope,” Dad said.

James thought of lots of things to say.

But nothing sounded right, so he put his arm around his father, and they watched the sun set together.

Dad was buried on a tall hill, overlooking the valley where their house rested, and James stayed around his mother all the time for as long as he could, while she took the chance to sleep in late and rest and recuperate.

The few days before the funeral had been distressing for him, because he found that the truth of

Dad is gone

had begun to usurp his memories, retroactively erasing his father from his recollections—so he’d had to fight that, with photographs, reconstructing a skeleton in his mind of who his father had been, finding it sometimes not aligning perfectly with what he thought he remembered. And he hated that the sharpest picture he had of Dad was of a weak animal in a hospital bed, and he fought to recall the vigorous, looming figure of his youth. Sometimes, he succeeded.

The last few days had been the hardest. Mom never left his side in the hospital room, sleeping in the hard wooden chair. After a few days Dad started talking about things that weren’t there, and staring off into the distance, and then he would call your name and squeeze your hand and you wouldn’t be able to understand the words through the thickness in his voice.

On the last day he hadn’t spoken at all, and by the time James arrived in the morning Mom said that he’d stopped squeezing her hand back, and he lay there in the soft white bed sucking air like a fish on land, then lying deathly still; gasping, sucking, wrenching the oxygen from the atmosphere by force, then slumping, spent from the effort.

After a few hours of this, the gasping became less pronounced, and the hills and valleys of the heart monitor became an undulating stream, and the shrill sound of the monitor’s alarm became annoying, and they turned it off.

Then there was nothing left to do but watch his face turn yellow and his jaw stop moving and the man who was James’ father become something

other

than a human being, something that was diseased meat and bone and cloth that there was nothing of Dad in at all. And they cried and held each other and sat very still for a very long time, weeping into each other’s arms.

And that night, when they came outside to the parking lot, they found that Mom’s car was dead, that its battery had been drained from the lights being left on, and without any further tears they left it in the parking lot, an empty machine, a shell without a driver.

James wondered if his father had heard him on that last day, whether his unresponsive hand and closed eyes belied some deep consciousness that had survived buried inside the ceasing functions of his body, and if the echoes of his voice had carried all the way to it. For whatever it was worth, he’d told the mute Dad not to be ashamed or guilty; that it wasn’t his fault; that he’d done everything he could. That he was loved.

He wondered if Dad had been disappointed in him, for not believing in Tim, or for not attending the meetings, or for continuing to push the medication that he so despised. Dad hadn’t taken any pills at all, the last month or so, but his lymphoma by then had spread to the stomach and lungs and bones and so there wasn’t really any point and James felt bad for arguing, for making a big deal about the pills, for causing his father stress about that and Tim and everything, for refusing to just go along.

He stood on that new patch of grass, where he could very easily picture the long oaken box a man’s height under his feet, and recalled his reluctance to view the body, to have his recollections of the strong man of his childhood contradicted by physical reality. But it hadn’t been bad—the figure in the box was just a thing of tissue and skin, and posed no threat to the memories that were now the only thing that James had left.

But even still it was

something

, it was

physical

, it was better than ether and void and thought and dreamstuff, and so he stayed there on the green hill overlooking the valley as the wind blew heavenward.

And in that lonely moment he thought about Tim, and wondered if he would call Tim to ask him to untie the knot he felt deep in his guts. And then James wondered if there wasn’t something of his father in him after all.

Story by David Malki !

Illustration by Danielle Corsetto

“

IT’S

A

NEW

PARTY

GAME

,”

SAID

NORMA

, AS

SHE

PUSHED

A

SMALL

CART

INTO

THE

LIVING

ROOM

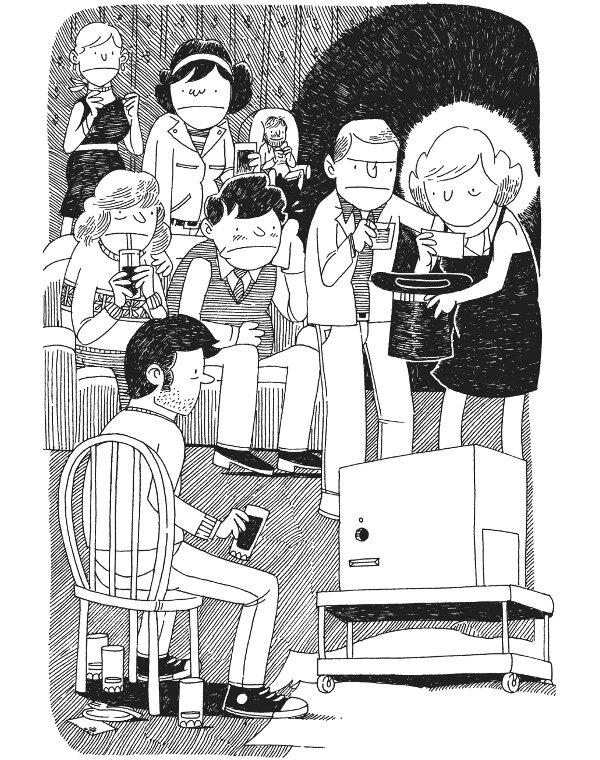

. A white sheet draped over the top hid the cart’s burden—something boxy, no larger than a microwave oven. The guests all turned to watch as the little mystery was wheeled into the room, squeaking slightly, leaving a visible groove in the carpet. Norma stopped and stood; she made no move to uncover her secret, only smiled at the seven faces around her. Every guest had a fresh drink in hand and a hot

hors d’oeuvre

on a toothpick. Music played loudly enough to keep the room cheerful, but not so loud as to hinder conversation. And now she had piqued everyone’s curiosity by wheeling out this odd little cart. Norma was an excellent hostess.

“And it’s called ‘Death Match?’” one of the guests asked—a florist with the unfortunate name of Melvin. “That sounds awfully violent,” said another.

Sid said nothing, just watched quietly as the other guests responded to Norma’s little show. Her entrance wasn’t a huge spectacle—not like in the old days of birds and smoke. She just enhanced the presentation a bit with her dashes of secrecy and drama. Norma still had a sense of staging, Sid had to give her that. She appreciated the way a hint of anticipation can make any event even more memorable than it might have been.

Sid already knew what was under the sheet. Norma had warned him of what she had planned because she knew how much he would hate it. He had tried to dissuade her, of course, but she insisted on proceeding, just as she insisted that he be there as always. They’d been divorced for three years, but he still couldn’t bring himself to say “no” to her. He never could: That’s why he was thirty-eight years old and on his third career. His second career had lasted exactly as long as his marriage, and had been entirely her idea. He missed it almost as much as he missed her.