Machine Of Death (24 page)

Authors: David Malki,Mathew Bennardo,Ryan North

Tags: #Humor, #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Horror, #Adult, #Dystopia, #Collections, #Philosophy

DR. NELSON

: A stroke before midnight?

DR. ROSCH

: Sure! For drama’s sake. Then, one minute later, at midnight, we actually run the blood sample we took earlier through the machine. What do you suppose it’ll say?

DR. NELSON

: Something about being killed with a hammer, of course. It’s already done.

DR. ROSCH

: Precisely.

(A beat.)

DR. NELSON

: So?

DR. ROSCH

: You don’t see it? What if we could ship this box further away? What if Dr. Merry lived thousands of light-years away, and we could somehow get the box to him? If we set a time for him to do the killing, and for us to run the blood through the machine shortly afterward, then as soon as we read the machine’s prediction, we’ve sent information faster than the speed of light.

(Dr. Nelson thinks for a second.)

DR. NELSON

: Well, it’s an interesting thought experiment, but we can’t send things thousands of light years away, much less with precise timing. The rat would be long-dead by the time it arrived.

DR. ROSCH

: Sure. But if we could—

DR. NELSON

(interrupting)

: Even if we could, no information is actually being transmitted. If Merry’s good at following our orders, he’s going to kill the rat, yes? And we could expect this when we sent the rat in the first place. Besides, we could run the test as soon as we take the first blood sample, and we’d already know how it’s going to turn out. So yeah, we’re getting information about the future, but it’s not breaking any universal speed limits. The information was always there, encoded in the rat’s blood.

DR. ROSCH

: Hmm.

DR. NELSON

: But…but…

(He trails off, lost in thought. Dr. Rosch stares at him for a moment.)

DR. NELSON

: You’re just using one rat in your example.

DR. ROSCH

: Yes. Just to make things easy to imagine. We could send lots of rats—we probably would, in case some of them died for whatever reason.

DR. NELSON

: Okay. Okay. What if we made, say, 100 of these life-support boxes, and put a few rats in each.

DR. ROSCH

: So, about 300 rats.

DR. NELSON

: Yes. And we don’t send these rats light years away or overseas, we just…put them in storage.

DR. ROSCH

: Each collection of rats in their own life support box…

DR. NELSON

: Right! We number each box.

(excitedly)

And a lab rat, properly taken care of, lives for, what, 2-3 years?

DR. ROSCH

(slowly catching on)

: On average.

DR. NELSON

: So we put these rats in storage and then, 2 years later, or sooner, if need be…

(Dr. Nelson looks at Dr. Rosch, eyes wide with the idea.)

DR. NELSON

: ...We take them out.

DR. ROSCH

(understanding)

: And we kill them.

DR. NELSON

: But we don’t kill them all with a hammer to the head. We have a code.

DR. ROSCH

: Each death means something different.

DR. NELSON

: It’ll be noisy—we can’t trust the machine to make it clear exactly how each rat dies. But we’ve got more than one rat for each letter. And if we choose the deaths carefully…we should be able to minimize the overlap between predictions.

DR. ROSCH

: A different death for each letter of the alphabet. Each box equals one letter.

DR. NELSON

: We could send a message back in time to the point when we first took blood samples from the rats.

(Dr. Rosch and Dr. Nelson stare at each other.)

DR. ROSCH

: We’ve got to get to the lab.

Story by Ryan North

Illustration by Aaron Diaz

JAMES

SPOKE

UP AS

SOON

AS HE

HEARD

THE

DOOR

CLOSE

. “You went to that kid’s house again, didn’t you?”

His father sighed; his mother dropped her purse on the long stone table. “It’s late,” she said. “Go to bed.”

“You didn’t give him any

money

, did you?” James stood up, following his parents up the stairs. ”I don’t care if you sat there and nodded, or sang songs, or

whatever

you do there, but tell me—

please

tell me when that basket came around you just passed it down the line.”

“James, I’m tired,” his father said, and James heard in his voice that he was telling the truth.

It had started with the doctor’s visit a year ago. Dad had complained of trouble swallowing. The doctor had clucked disapprovingly at Dad’s lymph glands. He had taken some blood and scheduled some tests. He had not been surprised by the results.

“If there’s anything you want to do, anyplace you want to travel, anyone you want to see,” he had said, “I would do it now.”

James had seen the brightly-colored flyer in the mailbox, but hadn’t given it much thought and had thrown it away with the supermarket coupons. So he was surprised to see it later, rescued from the trash can, its glossy color beaming from the fridge beneath a smiley-face magnet.

He plucked it down and had already begun to crumple it when Mom stopped him.

“Doesn’t that look fun?” she said. “We’re going to the one next week.”

In garish red and yellow, the flyer announced that You, Too, could “Defeat the Machine!” A colorful cartoon hammer smashed a predictor box, starbursts flying out zanily. A beaming man in a tie beckoned to his new best friend, You. Bright blue type advertised an (800) number. Seats for the seminar were limited.

“Are you

joking

?” James sputtered to Mom, deeply afraid that she wasn’t.

She hadn’t been, and she and Dad had gone to the seminar, returning with bulging plastic bags crammed with flyers and handouts and brochures promising intensive weekend workshops and personal counselors and private consultations with Dr. Gene Eli himself. Dr. Eli (who, as far as James could tell, seemed to have a doctorate purely in smiling broadly) called himself an “industry-leading expert in recovery medicine,” which meant that his literature was peppered with positive, boisterous terms about

mankind’s potential for self-healing

and how the

psychic capacity of the human spirit

could surpass the limitations of current medical science.

Dr. Eli’s follow-along lecture notes—carefully annotated in Mom’s looping script—claimed that according to the laws of nature, ancient man should have become extinct. But mankind had, instead,

evolved

. According to Dr. Eli, the same impossible power that had allowed cavemen to conquer their murderous world already existed in

you

. With this power at your disposal, a slip of paper from a predictor box was no more a guarantor of death than chicken pox or diabetes —a thing to be conquered, a thing a person could overcome.

By now James had forgotten his skepticism, engrossed in Dr. Eli’s argument. He sat with his eyes unfocused for a time, suddenly certain of a raw, innate strength that lay latent in his blood, in his father’s blood.

When he finally turned the page, he realized with a start that he couldn’t make out the words: The sun had set, and the room was dark.

He reached up and snapped on the lamp. Blinking through the brightness on the page, he was suddenly angry at his own belief:

There

were the prices for the weekend retreats, the private consultations, the intensive one-on-one counseling. Clearly, Dr. Eli and his team of “recovery therapists” were not altruists. James felt a knot of revulsion catch in his throat. His blood bellowed betrayal.

When his parents returned from an afternoon doctor’s appointment—with another set of new pills for Dad, these with side effects that could damage his heart—James waited until Mom had eased Dad into his recliner and turned on the TV before pulling her into the kitchen.

“These guys, this Dr. Eli, they’re just taking your money,” he said. She shook her head, like she’d already considered the thought and dismissed it.

“All the meetings are free,” she said. “We’re not going on the weekend retreats or anything; we can’t afford them anyway. We’re not giving them any money. And it brightens him up—it brightens both of us, a little. What’s so wrong with that? After these depressing appointments every day, what’s wrong with a little

hope

for a change?”

James clenched his jaw before his mouth could spit out,

But it’s

false

hope

. He stared at the cupboard door, willing his breathing to slow, willing his eyes to focus. When he turned back, Mom was halfway up the stairs.

Dad still sat on his recliner, head leaning to one shoulder, eyes pointed at the TV but not really watching. James took a few steps into the living room, then sat on the couch. Dad rolled his head around, lifted a hand. James grasped it—grip still strong; skin thick and calloused from decades of labor. His own hand felt thin and smooth in comparison. He felt young.

“How’s it going?” Dad asked him. “How’s that car doing? You still checking the oil every day? Oil and water?”

“Yeah,” James lied. Dad always bugged him about this, and James always forgot. “Looks good.”

“Keep checking it, every day, every day,” Dad said. “If your oil gets too low you’ll blow that engine, and then it’s a headache.”

They sat in silence for a few minutes, watching an antacid commercial, which was followed by a drug commercial that mainly consisted of old people pushing their grandchildren in swings and a long list of quickly-read side effects.

“These pills,” Dad said suddenly, sitting forward in his chair, “these pills they give me, new pills all the time, new ones, new ones, the pills are worse than the disease! Heart problems, they said today, this one has risk of heart problems. I

never

had heart problems! Never in my life. What

is

this, when the medicine is more problem than the…than the first problem? I never

heard

of this!”

He settled back, and released James’ hand to fidget with the pillow beneath his lower back. The news came back on; the screen filled with sports scores.

James looked up the stairway, up where his mother had disappeared, and then leaned closer to Dad, trying to think of something to say, anything. He finally settled on, “So, you’ve been going to those meetings, huh?”

Dad looked over. “Yeah, this Dr. Elo, Oli, whatever his name is. I think he’s Egyptian—he looks like an Egyptian.”

“What kind of stuff does he say?”

“Oh, I don’t know, bunch of baloney mostly,” Dad said, and James breathed a sigh of relief, leaning back.

Dad continued. “He says all kinds of junk, about evolution, I don’t know what he’s saying. He wants to sell you a weekend retreat, they call it. With his fancy doctors, you go up in the mountains for a weekend, they take a look at you.”

“Yeah, I read the brochure.”

“It’s a bunch of baloney,” Dad said. “Your mom, she likes to go, so we go. I don’t know what it’s about. But I tell you”—here he looked over at James, and leaned in close, and lowered his voice—”I tell you, some of the people at those meetings—old people, sick people, these people look like they died

already

.”

“It’s the last day before the seminar leaves town,” Mom said. “You know how much it would mean to your dad.”

“I don’t think those meetings mean as much to him as you think they do,” James yawned, rolling over in bed, trying to pull the blankets from Mom’s grip. With a single yank, she pulled them off, and James curled tightly into himself.

“We’re going,” she said, and they did, all three of them.

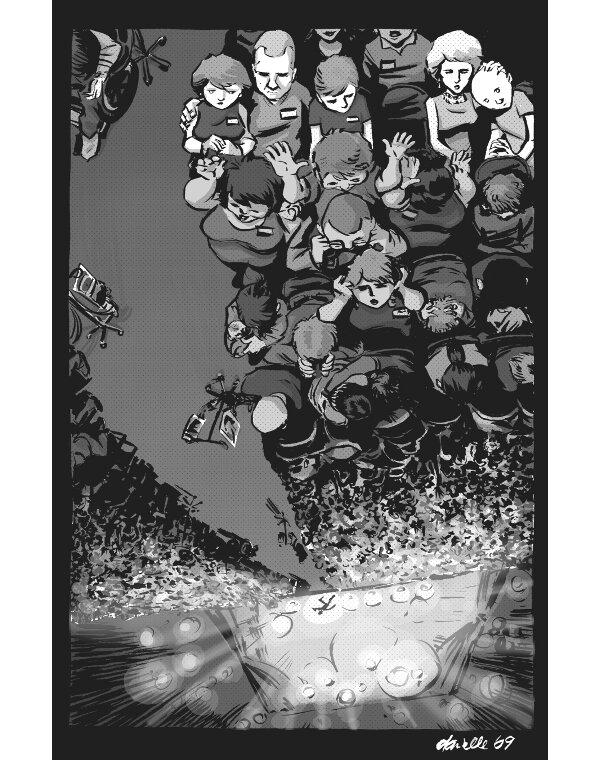

Dr. Eli’s seminars were held in the banquet hall at the Hilton. By the time James and his parents arrived, the place was already packed. Wheelchairs crowded the aisles; near the front, a few gurneys lined the walls, attended to by nurses monitoring IV trees. As soon as he passed through the doors, James was hit by the smell of Mineral Ice and sweat.

Dad handed him a paper name tag. “Here,” he said, and James saw that his own name had been pre-printed on the tag by a computer. Mom and Dad already wore theirs.

They elbowed their way through the crowd, moving past sad-eyed old men and heather-haired old women, past fat men in sweatpants and sickly women with track marks. There weren’t three seats together anywhere but the very back, in the corner. Dad carved a passage between a huge woman in a muumuu and a quivering girl holding a very young infant. James saw that the girl was trembling so hard that her baby was becoming dizzy.

They sat on folding chairs next to a delicately poised middle-aged woman with elaborately sprayed hair. Her teenaged son sat next to her, his bald, chemo’d head resting on her shoulder. James watched her idly stroke the boy’s neck and shoulders with her painted fingernails. The kid’s bare scalp was textured with goose-flesh. He shivered.