Lynette Roberts: Collected Poems (5 page)

Read Lynette Roberts: Collected Poems Online

Authors: Lynette Roberts

Travelling down through ‘currents/ of ice, emerald streams and blue

electric

lakes’ they return to the post-war desolation of a ‘bleak telegraphic planet’, finding

a ‘Mental Home for Poets’ in the now-derelict bay. There are perhaps associations

of the Fall, but the divergence between the ‘

argument

’ and the final stanzas of the poem cause problems: the ‘argument’ is pessimistic

and suggests the sundering of the couple and failure of

liberation

and renewal. The girl, alone, ‘turns away: towards a hard new chemical dawn’, the

soldier ‘walks meekly into the mental home’. In the poem, however, the feel is on

the contrary optimistic, defiant, vibrant:

Salt spring from frosted sea filters palea light

Raising tangerine and hard line of rind on the

Astringent sky. Catoptric on waterice he of deep love

Frees dragon from the glacier glade,

Sights death fading into chillblain ears.

This volume also presents a selection of Lynette Roberts’s uncollected and unpublished

poems, many of which were intended for the volume that never appeared,

The Fifth Pillar of Song

. Eliot’s rejection of the book is understandable. Though there are many original

or successful poems, it is uneven and confused. Its best poems are those, like ‘The

“Pele” Fetched In’ or ‘Saint Swithin’s Pool’, which have simplicity and depth, and

in which there is a sense of the cosmic embroiled in the everyday. Many are simply

unsuccessful or underworked, or caught up in bombast and capital-lettered abstractions.

The poems chosen here are intended to represent the best of the unpublished or uncollected

work, though a few examples of latter

category

are included to give the reader a sense of the whole. The final section of the book

contains three texts. The first is the ‘ballad for voices’

El Dorado

, a breathlessly told, Wild-West-style adventure about the murder of Welsh colonists

by a group of Indians in 1883-4.

El Dorado

was a poem for radio, and should be considered as such: it has colour, adventure

and pace, but it

does not measure up – as poetry – to the rest of Roberts’s work, and is not a gaucho

Under Milk Wood

. Also in the appendix is an article by Roberts on Patagonia, first published in

Wales

, in which she discusses the incident retold in

El Dorado

, and the text of a radio talk she gave on her South American poems.

It seemed inevitable that Roberts’s poetry would be charged with ‘

obscurity

’, a charge often levelled against women poets of a modernist bent – Mina Loy, Marianne

Moore, Laura Riding, to mention just three (it is always the men who are ‘learnèd’

and the women who are ‘obscure’.) In a letter of 3 December 1944, Graves wrote to

Roberts to air his own doubts:

Eliot and Pound have set a bad example. Your lines all work out surely, I grant you,

which is very rare in the present slapdash pseudo-

intelligent

world; and of course in

Cwmcelyn

you are doing what every poet I suppose must do once at least: show his or her awareness

of what a frightful mess the world of ideas has got into because of Science taking

the bit between its teeth & bolting. You are saying ‘To interpret the present god-awful

complex confusion one must unconfusedly use the language of god-awful confusion’…

[T]here are a great many small points I’d like to question you about: such as your

views on how much interrelation of dissociated ideas is possible in a single line

without bursting the sense…

20

Graves could hardly disguise his ambivalence. Her reply is remarkable for its self-assurance:

It is a long heroic poem. I cannot change it; but I believe a stricter

technique

would have reduced the poem and clarified what I wanted to say. On the other hand

it would have been less pliable and adventurous and may have constrained that which

I had purposely set out to do: which is to use words in relation to today – both with

regard to sound (ie: discords ugly grating words) & meaning.

21

A similar uncertainty about Roberts’s diction underlies Eliot’s query about ‘Poem’

(later the opening of Part II of

Gods

): ‘The words

plimsole, cuprite

,

zebeline

and

neumes

seem to exist but I think that bringing them all into one short poem is a mistake’,

he tactfully suggests in a letter of 24 November 1943. The following month he accepts

these words, telling her that he is convinced by her reasons – ‘I like your defense

of your queer words and now accept all of them, but I am still not happy about

zebeline

’.

22

Eliot’s are

editor’s queries, but Graves’s are more obviously grappling with something larger.

The point of view Graves puts forward in his letter to Roberts is articulated in many

of his critical interventions, from the

Survey of

Modernist Poetry

(1927) which he wrote with Laura Riding, to the Clark Lectures of 1954. For Graves,

‘modernism’ is essentially a fractured response to a fractured world: for all its

innovative bluster, it is tired, pessimistic and passive. It reveals something of

Lynette Roberts’s faith in what she was doing that she should have stood her ground

so single-

mindedly

against poets of the stature of Graves and Eliot.

In a review of

Gods with Stainless Ears

, the

Times Literary Supplement

critic complained that ‘the vocabulary needs a chemical glossary’, going on to dismiss

‘the contrast between the high tragic tones of the poet and the naivety of her incidents’

as ‘irresistibly ludicrous’ (16 November 1951). The review is dismissive, but the

reviewer has a point about the poem’s contrasts: between grandiloquence and something

altogether more artless or innocent. Tony Conran, in an essay on Roberts in his book

Frontiers in

Anglo-Welsh Poetry

, offers perhaps the most perceptive comment made on what we could call Roberts’s

contextual lack of context:

As with other primitives [Conran talks about John Clare and Emily Dickinson] these

poets’ viewpoint is eccentric to their culture’s literary norm, though perhaps derivable

from it. The primitive’s isolation is in a sense a reflection of the isolation of

all modernist art. That is perhaps why Henri Rousseau lived happily beside the cubists.

But it is not

necessarily

the same thing as modernism, though most primitives would certainly claim to be ‘modern’.

Modernists create an environment in which primitives can come to the fore; so much

so that ‘primitive’ and modernist can often be regarded as two sides of the same coin.

23

Conran is right, not just in the detail of Lynette Roberts’s place in the poetic tradition,

but in the more sweeping suggestion he makes about the

relationship

between the modernist and the primitive. We need not go along with the term ‘primitive’

– even if Conran is careful to use it in inverted commas – because after all Roberts

was educated, well-read, artistically trained, and, for all her ‘outsiderness’, moved

in literary circles, but we can see what he means. We might prefer the term ‘naïve’

in the specific sense of the naïve painters, the tradition of Henri ‘Douanier’ Rousseau.

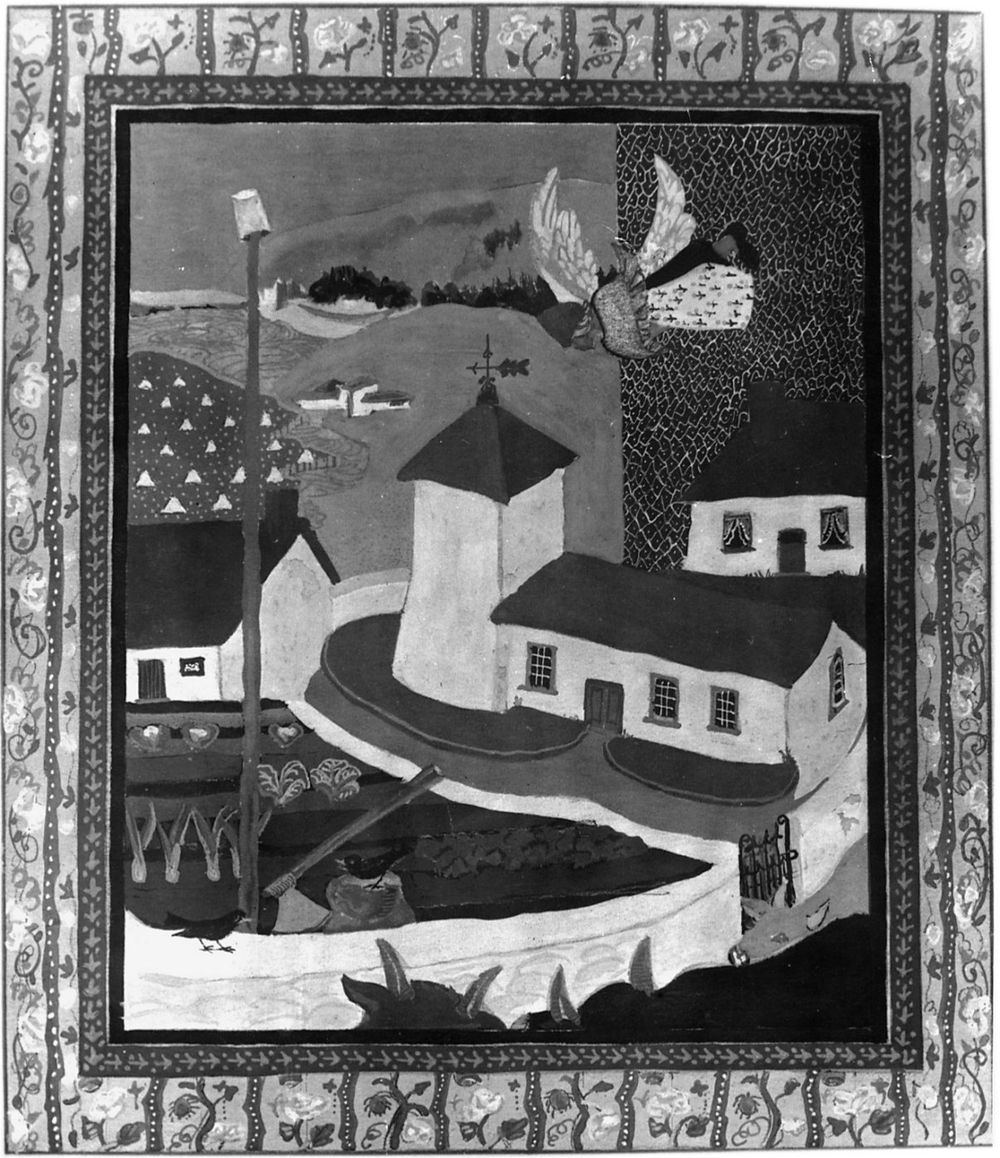

A painterly poet, Lynette Roberts was herself a painter in the naïve tradition – one

of her finest paintings, of Llanybri old chapel, depicts an angel circling above the

village, with the bay in the background and enormous leeks rearing out from the vegetable

patch (see opposite page). The painting is framed with a home-made border, designed

by Roberts and based on the apron worn by Rosie, her neighbour. Often intricate, exact

and

harmonious

,

the ‘naïve’ painting is also eclectic in its combinations of images, and plays fast

and loose with perspective and proportion, facets which, in poetry, might be compared

with tone, and specifically with irony, itself the manipulation of emotional distance.

Roberts is certainly not ironic; she is never above her subject, and her subject is

never beneath poetry. She writes a ‘Heroic Poem’ and she

means

heroic. The past is no refuge but a fund of analogies, an archive of correspondences;

and there is no fear of the future. Her subject is ‘

today which is tomorrow

’ (

Gods with Stainless Ears

, Part V). Her work has no trace of cultural pessimism – on the contrary – and hers

is not a poetry of ‘shored fragments’. It may be ‘difficult’ – indeed it seeks out

difficulty as much as it seeks to ‘speak of everyday things with ease’ (as she writes

in ‘The Shadow Remains’) – but it is not contorted with

self-reflexiveness

, knowing allusions, or arcane learning. Even the speech fragments, however cut loose

from their sources, are transcribed from real utterance, so that raw, unmediated speech

coexists with the most

overwrought

language. This is not the stylised demotic of

The Waste Land

. She also has an enabling – and in the best sense unsophisticated – belief in language’s

sufficiency. We cannot imagine Pound or Eliot writing in their diaries: ‘I experimented

with a poem on Rain by using all words which had long thin letters [so that] the print

of the pages would look like thin lines of rain.’ Writing poetry is not ‘a raid on

the inarticulate’ with shoddy

equipment

, but a way of bringing word and World into alignment. Her extraordinary freedoms

of scale, subject and imaginative conception, her omnivorous diction and imagistic

special effects, may at first glance appear similar to those of other modernist poets,

but they are unique to Roberts, and to what we could call her ‘home-made’ world.

Llanybri Old Chapel

by Lynette Roberts

How to ‘place’ Lynette Roberts? And do we need to?

Poems

and

Gods with Stainless Ears

are unique books. Their freshness and originality are

difficult

to overstate, and cannot simply be explained by means of an intersection of influences

and the convergence of biographical and

cultural-historical

circumstances. Certainly her work can be seen in the context of modernism, in whose

second generation Roberts belongs. It obviously shares something with that of Pound

and Eliot, but perhaps the nearest to her in vision and conception is David Jones,

another poet who created from, and was created by, war and Wales. Her fascination

with dialect and her cosmopolitan’s idealisation of the simple life, combined with

a contrasting taste for new-fangled, specialised or abstruse vocabulary, suggests

something

along the lines of Conran’s modernist-primitive symbiosis. Roberts’s work is set

within a few square miles of coastline, among a particular people, their customs and

their idioms. Roberts has a sense of the absolute

coterminousness

of past-in-present-in-future, intertwined as in a Celtic pattern: the archaic is

a luminous guide to the contemporary, the mythical is a map of the real. Hers is a

world, as she writes in Part I of

Gods with Stainless Ears

, ‘where past/ Is not dead but comes uphot suddenly sharp as / Drakestone’. In her

fascination with archaeology and geology, her sense of place as the layering of time,

we might see unexpected (and strictly limited) similarities with the Charles Olson

of

Maximus

. In her modernism of the local she perhaps recalls (again in a limited but precise

way) the William Carlos Williams of

Paterson

. In other respects – its tendency towards emphatic alliteration and assonance, its

rhapsodic descriptions, vatic

registers

and grand abstractions – her poetry belongs to the 1940s, alongside the work of the

‘Apocalypse’ and New Romantic poets. As well as the poets of

this period, Roberts shares something with the artists, specifically with painters

such as Ceri Richards and Graham Sutherland, who worked on the peripheries of the

literary scene of the time. Most strikingly perhaps, her poetic aerial views are also

reminiscent of Eric Ravilious, war artist with the RAF, whose dramatic coastlines

and images of planes and submarines make interesting comparison with Roberts’s. Her

work is also part of the twentieth-century flowering of Welsh poetry in English, the

tradition of Dylan Thomas, Glyn Jones, Vernon Watkins, R.S. Thomas. Like these poets,

Roberts has learned from the Welsh-language tradition, not just in verse technique

but in literary heritage and cultural politics. Add to all this the work of Auden

and MacNeice, and we have a poetry bristling with contexts, alive to its time and

place even as it dazzlingly dramatises and reimagines them – a poetry open to influence

and example while perfecting its own distinct voice and vision.