Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (18 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The Heinkel 162A

Volksjäger

was another German wonder weapon that did not work out. Although about 275 were completed, the type is believed to have accounted for just one Allied aircraft in the course of the war. (Via

FlyPast).

The Messerschmitt Me 262

Schwalbe

was the only successful German jet fighter of the war, but it entered service too late and in too small numbers. (Via

FlyPast).

The world’s first effective jet night fighter was the Me 262B two-seater trainer fitted with radar and with the operator in the back seat. (Via

FlyPast).

Ghosts! Two

ex-Luftwaffe

aircraft seen at the Champlin Fighter Museum some fifty years on. Nearest the camera is a FW 190D; furthest is a Bf 109E. (Via

FlyPast).

Instead of telegraphing their intentions by forming up at high altitude in full view of the German radar, the British now took to crossing the Channel at low level, then climbing flat out just before they reached the coast. At the same time, increasing use was made of low-level penetrations by light bombers, which called for a different approach to the fighter escort mission. For the

Jagdflieger,

the leisurely wait at cockpit readiness, followed by a calculated climb to altitude, was now eliminated: the Spitfires, rocketing skywards at full throttle, were often already above.

With the advent of the FW 190A, this was not as critical as it once had been. The aircraft was a superb dogfighter, and its pilots used it as such. The previous summer, faced with slashing attacks by the 109s, the constant complaint of RAF pilots was that ‘Jerry’ didn’t stay and fight, totally ignoring the fact that in the 109 this was tactically correct. Now they were repaid in spades: in his new FW 190A, ‘Jerry’ stayed and fought as never before.

One of the Germans’ more successful actions took place on 2 June, when No 403 Canadian Squadron, an inexperienced outfit but led by New Zealand veteran Al Deere, flew as top cover on a Rodeo. The intercepting

Jagdflieger, I/JG 26,

led by Johannes Seifert, and

II/JG 26,

led by Müncheberg, waited until the Rodeo was homeward bound before, taking advantage of cloud cover, they moved into position.

The opening ploy was a high-speed run from astern by a single

Staffel.

Deere saw them coming and called a complicated three-way break and reverse to meet the attackers head-on. This not only effectively split No 403 Squadron off from the rest of the Wing but disrupted its formation integrity—not that there was a lot of choice. As the Spitfires pulled round, they were assailed from the flank by two more

Staffeln,

which had taken full advantage of cloud cover. A fraction of a second for a head-on burst at the original formation of FW 190s, then they were hit again from the other flank by a whole

Gruppe.

No 403’s Spitfire Vs, outclassed and heavily outnumbered, were decimated. Deere later wrote of this encounter:

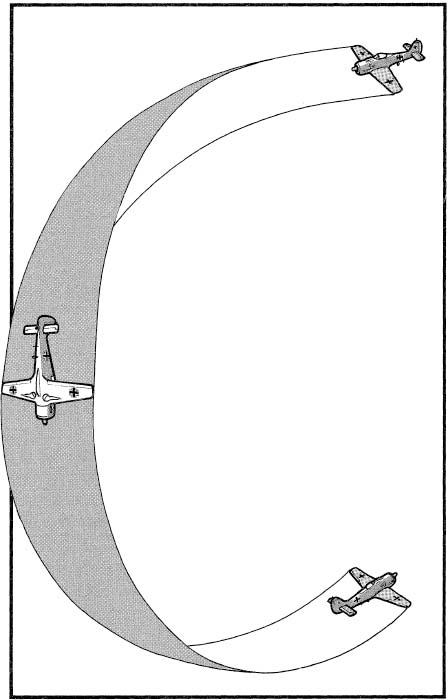

Fig. 14. The

Abschwung

Known to the British as the Half-Roll and the Americans as the Split-S, the

Abschwung

was a widely used method of breaking off action. It consisted of rolling inverted, followed by a hard pull into a vertical dive and a low-level pull out in the opposite direction. Not recommended

against a better-diving opponent.

I twisted and turned in an endeavour to avoid being jumped and at the same time to get myself into a favourable position for attack. Never had I seen the Huns stay and fight it out as these Focke-Wulf pilots were doing.

Of the original twelve Spitfires, eight were lost, one of which was written off after crash-landing at Manston, as were six pilots. German losses were nil. In this encounter Müncheberg claimed two aircraft, bringing his score to 81, and Seifert notched up the 35th of the 57 he scored before colliding with an American P-38 Lightning some seventeen months later.

After this, air activity eased considerably. The Spitfire IX started entering service, although it was some time before its numbers were sufficient to redress the Focke-Wulf threat. Then, on 19 August, came the large-scale amphibious raid on Dieppe. The British, supported by the USAAF, put up a massive air umbrella over the beach-head, with no fewer than 2,462 fighter sorties during the day. The Germans reacted in force, throwing in not only every fighter in the area but bombers as well. A massive battle for local air superiority ensued, after which both sides claimed victory. RAF losses totalled 106, of which 88 were fighters. Eight Spitfires of the USAAF also failed to return. German losses amounted to 48, of which only 20 were fighters. The most successful

Jagdflieger

on this day was Josef Wurmheller of

III/JG 2

who claimed seven victories, despite flying with a broken leg and concussion.

By the late summer of 1942 the Circus was rapidly falling into disuse. The superiority of the FW 190A over the Spitfire V made it a losing proposition for the British, while low-level penetrations by light and medium bombers were far more damaging than the ‘bait’ bombers had ever been. In any case, a new factor was fast emerging. The USAAF had long been determined to carry out precision daylight attacks with massed formations of heavy bombers. By August the first units were operational. Two days before the Dieppe raid, with a close escort of four squadrons of Spitfire IXs, a dozen B-17 Flying Fortresses attacked the marshalling yards at Rouen. All returned safely.

It was the shape of things to come. At first the American heavy bombers rarely ventured beyond the range at which Spitfires could escort them, but, as they gained experience, so they became more confident. Finally they ranged deep into Germany without fighter escort, and, while they suffered heavily, they set the

Jagdflieger

new and very difficult problems. But that is another story.

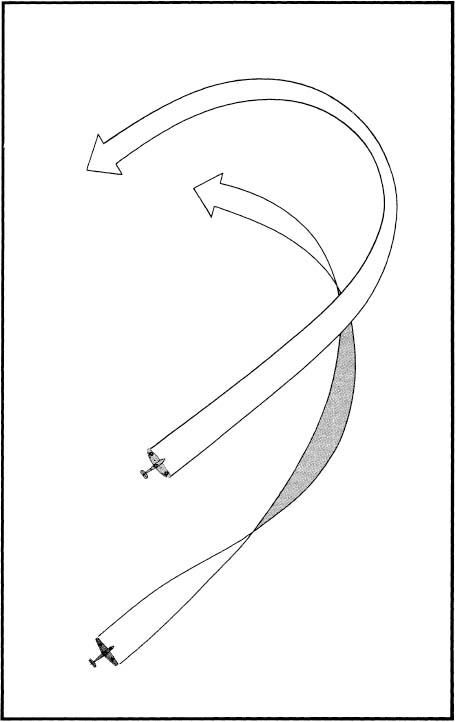

Fig. 15. Vector Roll Attack

Superiority in the rolling plane could be used to defeat a better-turning opponent. Rolling away from the direction of the turn allowed the pursuing fighter to cut the corner. This was, however, a double-edged sword: American Thunderbolts often used the vector roll against Bf 109s.

Experten

Many of the leading

Experten

of the two years of the Channel campaign were ‘old heads’, blooded in France and the Battle of Britain. Experienced in flying against the RAF, they continued from where they had left off the previous summer. Others were posted to the Eastern Front for ‘Barbarossa’ and returned to the West later. Conditions in the East were so different, and the quality of the opposition so low, that they became careless. Flying against Fighter Command this was potentially disastrous, and often they failed to last long.

Although the established

Experten

continued to add to their scores on the Channel coast, hardly any really high scorers emerged from this theatre, probably because conditions were not conducive to the survival of novices. Siegfried Lemke (96 victories) joined

I/JG 2

in the autumn of 1942. Wilhelm-Ferdinand (Wutz) Galland, brother of Adolf, scored 55 victories with

II/JG 26

between 27 July 1941 and his death in action at the hands of American ace Walker Mahurin in August 1943. Gerhard Vogt of the same unit amassed 48 victories between 6 November 1941 and 14 January 1945, when he was caught at low level by Mustangs. As an aside, the third Galland brother, Paul, was shot down by a Spitfire on 31 October 1942, his score a respectable 17.

KURT BÜHLIGEN

Bühligen joined

II/JG

2 as a humble

Unteroffizier

in July 1940. Success was a while coming: his first victory was not until 4 September. His score mounted slowly until 13 June 1941, the day he found his ‘shooting eye’. Flying a Bf 109F with the

Gruppe Stab as Kacmarek

to the

Kommandeur

, Heinrich Greisert, he intercepted a Circus near Boulogne:

I came down and then up fast with the

Kommandeur

and we each selected a Spit. I watched my sight ring fill with the wingspan and came on still closer. I aimed below, the Spitfire was fast, and when I was very close I opened fire. The

Kommandeur

was doing the same. A big dogfight now developed but I managed to stay behind this one and my shells poured into him. Pieces started to fly backward, then there was black smoke. He started down. There was no ’chute. The

Kommandeur,

I think, got a Spitfire also, but we had by then become separated. I saw my victim go down and then looked around. I saw the

Kommandeur

trying a pass on another Spitfire. He was closing too fast and instead of going under the Spit he pulled up and passed over his tail and continued up to the left, as if to come round for another pass. But the Spitfire pilot turned left too, to come up and around behind him. I was in position to curve in from behind and follow the Spit and I turned as sharply as I could on his tail. He was intent on shooting down the

Kommandeur.

I managed to gain, and hung on in the turn. When very close I opened fire again and almost immediately saw hits. White smoke began to trail backward and I kept firing. Then half his tail came off.