Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (28 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

Perhaps Harrison’s insistence that the number sounded like Coward had finally driven Lerner and Loewe almost to ditch the original premise of the song. Until the modulation at bar 96, there is not the slightest mention of a nation other than the English. Rather than setting the character of the English as an explanation for their sloppy linguistic habits in relief with the strict education of other nations, this lyric lists the positive aspects of the English, and in particular, how they display courage (“The English will fight without a whimper or a whine”) or rigor (“The English will go to any limit for the King”), in many respects other than language. This is not one of Lerner’s happier creations, however, and aside from the development of the middle section, Loewe’s setting diverges almost pedantically from the original music. Compared to the fluidity of “Why Can’t the English?” even in its initial form, “The English” has a choppy texture and the melodic line is constantly broken by rests.

The definitive version of the song exists not only in Loewe’s autograph, the published vocal scores, and full score, but there is also a copy of the same copyist’s score referred to earlier, annotated throughout to indicate the musical changes required to bring the score into line with the final version of the lyric (which is not, however, included).

45

In addition, a lyric sheet dated January 27, 1956, gives almost the final version of the song, with the exception of the lines about the Americans (which is still sung rather than a spoken aside), the French (which is in the second person rather than the third, i.e., “The French never care what you do” rather than “… they do”), and the penultimate line of the song is sung (“Use decent English?”) rather than left up to the orchestra.

46

The differences between Loewe’s score and the published edition are minimal, involving mainly some disagreements between the placing and type of articulative gestures (for instance, accents instead of staccato dots) and Italian terms (Loewe has “Vivace” at “Hear them down in Soho Square”; the published score has “Vivo”). A couple of bars also lack their final accompaniment pattern, but the score largely represents a version that could be put into print. Interestingly, the manuscript paper on which the joke about the Americans appears is of a different brand to the previous two pages (Chappell rather than Passantino), while the final syllable of the word “disappears”—which begins the new page and is followed in the next bar by the spoken line about the Americans—is not in fact written down. Furthermore, the two bars of accompaniment that follow the musical tacet have clearly been erased and rewritten, and there is also evidence of the joke about the French (squeezed into the last bar on the page) having being rubbed out and replaced (though Loewe omits the word “actually” from the revised version—probably due to a lack of space on the page). This all fits in with the evidence about final revisions to the song and shows that Loewe revised his personal manuscript to document the changes.

As before, the full score of the number is a complicated document rather than a consecutively written, neatly produced manuscript. It is the work of both Lang and Bennett and contains numerous modifications. Broadly speaking, bars 1–95 (up to “Oh, why can’t the English learn to”) are Bennett’s orchestration, and 96 (from the key change at “set a good example”) to the end are by Lang. The introduction seems to have caused a few problems: the original orchestration consisted of a solo clarinet giving Higgins his opening pitch (A) and the harp playing a D-major scale from A to A to strengthen the lead-in. This was rejected, and instead Bennett wrote a short A-major chord on all the instruments, perhaps to act as a more assertive introduction for Higgins. That in turn was crossed out, however, and the two-bar bassoon introduction that appears in the published score was added. Curiously, this, too, was crossed out, but was later reinstated for the published show. The first three pages of score contain significant alterations, usually with lines being taken away from one instrument and given to another or the harmony being filled out. There are also places where changes were indicated but went unused in the definitive version. An example is in bars 14 and 15, where Bennett added trumpet parts to accompany Eliza’s cry of “Aooow,” but the final orchestration does not include them. Another case is in bars 34–39, where the original orchestration was saturated with busy sixteenth notes in the flute and oboe parts; Bennett replaced them with a eighth-note motif on the trumpets’ staves, indicating with arrows that they are for flute and oboe. Such examples are to be found throughout the score. Lang’s part of the orchestration can be dated fairly accurately, because he clearly orchestrated the version shown on the lyric sheet from January 27 (i.e., almost the final version, but not quite). The line about the Americans is written in its sung version but crossed out and changed to allow for the new spoken line; the comment about the French is spoken but in the second person rather than the third; and the line “Use decent English” still appears. Aside from this, the final two bars have been crossed out and replaced with a new version on the subsequent page, proving that, no less than Lerner and Loewe, the meticulousness of the orchestrators knew no bounds.

In his autobiography, Lerner describes how the composition of both “Why Can’t the English?” and “I’m an Ordinary Man” was the result of having met Harrison and evolved a style of music for him. Supposedly, the two songs took “about six weeks in all to complete.”

47

“I’m an Ordinary Man” replaced “the totally inadequate” “Please Don’t Marry Me” and was greeted with enthusiasm by Hart and Harrison.

48

The few surviving sources for the song uphold this image of a smooth creative process. Levin’s papers contain the earliest version of the lyric, both as a loose lyric sheet and as part of the

rehearsal script. The words are almost the same as in the published version, with a few minor edits.

49

Lerner’s only substantial change improved one of his images: “I’m a quiet living man / Who’s contented when he’s reading / By the fire in his room” became “I’m a quiet living man / Who prefers to spend his evenings / In the silence of his room.” Whereas the original picture merely portrayed Higgins as bookish, the replacement promotes the stony “silence of his room”; the point was not to show his scholastic side but his solitary, unsociable nature.

50

Not surprisingly, the autograph score of “I’m an Ordinary Man” in the Loewe Collection is a fair copy. Although it does not match the published vocal score, it contains only one major difference.

51

The passage “Let them buy their wedding bands / For those anxious little hands” was originally punctuated by two imitative gestures in the music. These are crossed out but are still legible. The material in the second half of the song that repeats the earlier music is written out in shorthand with the melody alone; Loewe indicated with numbers where the piano part was to be copied from the first half of the song, suggesting the score was written for the use of the copyist. This is corroborated by the fact that Bennett’s autograph full score uses the same earlier version of the lyric as Loewe’s autograph. The orchestration is largely free of corrections and modifications: the one-bar flute melody following the line “free of humanity’s mad inhuman noise” was cut, as was the nine-bar harp part after the thrice-repeated “Let a woman in your life” near the end, and there are some small additions of expressive markings and string bowings in pencil. Otherwise, the number does indeed seem to have been written with ease, as Lerner suggested.

52

Like Eliza’s “Just You Wait,” Higgins’s “Ordinary Man” is constructed with a freedom that helped to portray the two sides of Higgins—charm and arrogance—within the same number. The verse is roughly twelve bars long, and the gracefulness of the dotted rhythms, gently descending harmonic lines and flexed, rather than strict, triplets add to Higgins’s charm, even if he is arrogant in his idealized description of himself. With the refrain comes a shift to the subdominant, E-flat major. A typical rising-and-falling Broadway thumb-line creates unrest while Higgins sings “But let a woman in your life,” and many of his lines are punctuated by chromatic scales in the woodwinds. A sinister edge is added by the use of the subdominant minor on the lines “Then get on to the enthralling / fun of overhauling you.” The larger gesture is that Loewe paints Higgins’s description of himself in a tranquil light and his description of life with a woman as—literally—a nightmare: everything about the verses is relaxed, but the refrains are uneasy throughout, complete with howling high woodwind scales. This contrast is brought to a head at the

end of the song, when Higgins turns on several phonographs with “gibberish voices” playing on them, while the music whips itself into a frenzy until Higgins suddenly turns them off and makes his final statement: “I shall never let a woman in my life.” No less than in the Soliloquy from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Carousel

, which has long been held up as the outstanding example of a musical monologue in loose form, Loewe is capable of tying together disparate musical strands to create an insight into a character’s psyche.

Likewise, there are several different types of material in “A Hymn to Him,” rather than a regular structure. The song begins without introduction, and the declamatory manner of the lyric for the verse is matched by a simple vamp accompaniment. A transition passage, during which Pickering calls the Home Office to get help in tracking down Eliza after she has bolted, takes us into D major, and the same material is repeated with a slight melodic variation. The refrain is a self-righteous march in 6/8 time (from bar 59). The use of compound duple time here is clever, because it allows the composer to mix a martial character with Higgins’s characteristic elegance, whereas a straight common-time march could have been heavier. At bar 79, Loewe turns the ascending “Why can’t a woman” theme on its head and writes a descending melody for “Why does ev’ry one do what the others do?” Then at bar 90, the music briefly moves into cut time as Higgins delivers his punch line (“Why don’t they grow up like their father instead?”). This alternation of time signatures continues throughout the song, then in the final refrain Higgins finally comes clean and says what he has been thinking all along: “Why can’t a woman be like me?”

“A Hymn to Him” was one of the final songs to be completed. Lerner explains that it was added after Harrison’s worried reaction to the show during its first rehearsal: “His face grew longer and longer and his voice softer and softer. … Somehow Higgins had gotten lost in the second act and because this is the central story, I felt his concern was justified … I turned to Fritz and Moss and said that I thought Higgins needed another song in the second act.”

53

Harrison confirms this chronology and motivation in his autobiography, adding that Lerner’s wife invented the title “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?” and that the song did not reach him “until almost the last week of rehearsals.”

54

None of the pre-rehearsal outlines of the show contain a reference to the song nor does the rehearsal script, and there are no lyric sheets for the piece among the others in the Levin or Warner-Chappell materials. All of this confirms a late composition. However, the latter collection does contain an autograph piano-vocal score for the number.

55

The lyric, title, and vocal line are in Loewe’s hand, while Rittmann is responsible for the rest of the material

(accompaniment, expressive markings, etc.). She probably completed the score on the basis of Loewe’s melody, perhaps with the accompaniment taken down by ear on hearing him play it on the piano. There are a couple of changes of lyric in this version of the song.

56

In two places, fragments of lyric dangle out of context, saying “Ready to see you” and “We’re cold in the winter.” Another small difference is that both the Rittmann/Loewe score and Lang’s full score have “But by and large they [rather than ‘we’] are a marvellous sex.”

57

Otherwise, the lyric is familiar from the published version. The composer autograph in the Loewe Collection contains neither the introduction nor any sign that the original version of the lyric was ever present, so again this was probably written out later, perhaps for publishing purposes.

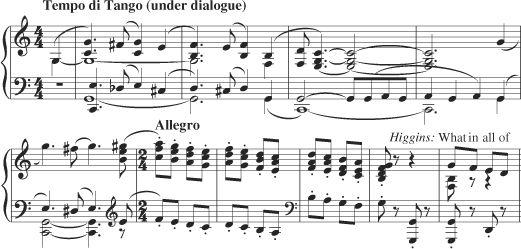

The Rittmann/Loewe autograph does contain a tantalizing musical difference, though. Whereas the published song begins without an introduction because Higgins speaks the first few words (“What in all of heaven”), this manuscript shows an extended introduction of nine bars (as shown in

ex. 5.7

), quoting five bars of “The Rain in Spain,” followed by an echo of the introduction of “I Could Have Danced All Night.” This creates an allusion to Eliza’s two songs of triumph on learning how to speak properly, and makes it more obvious to the audience that the music of Higgins’s “What in all of heaven…” is based on the introduction and verse to Eliza’s “Danced.” This makes new connections between both the characters (Higgins and Eliza sharing the same music) and the two acts (music from act 1 comes back in act 2 to link the two)—another instance of Loewe acting on both micro and macro levels.

One of Lerner and Loewe’s golden moves in the show is the positioning of “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.” By delivering it at the last moment they kept the tension high right through to the end of the story. On

November 29, 1955, Lerner wrote to Harrison in the wake of having composed the number, telling him about the character of the song (“funny, touching”) and its structure (a reprise soliloquy framed by new material):

Ex. 5.7. “A Hymn to Him,” original introduction.