Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (31 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

The full score of the number reflects the changes made during rehearsals. Most of it is by Lang, and it gives the original version of the verse, but the original middle section of the refrain was cut before the song was orchestrated.

18

Attached to the back of the score is an orchestration for the final version of the verse in Bennett’s hand; it also includes a revision of the orchestration of the four bars before the words “And oh, the towering feeling,”

as well as the final four bars of the number.

19

Lang’s part of the orchestration contains a couple of places where the harmonization has been slightly amended, but on the whole it was left as he originally wrote it. The composer’s manuscript of the song in the Loewe Collection represents a postcomposition document; it is fluently written and uses the published verse, as well as completely omitting the original middle section of the refrain.

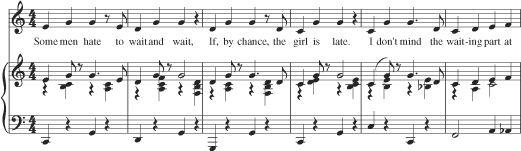

Ex. 6.3. “On the Street Where She Lives,” extract from cut section of original refrain.

Of the four key players in the drama, Freddy is the only one who does not undergo any kind of transformation.

20

The emotions of Eliza and Higgins veer throughout and Doolittle’s change of social class affects his life (if not his personality), but Freddy is the constant, foolish romantic. This is best represented by the fact that when his first-act song returns in act 2, it does so without modification. Freddy is silly: he sings in rhyming couplets and romantic clichés, and, with Eliza’s “I Could Have Danced,” his song is one of only two based on a conventional lyric arch. But if his constancy is comically extreme—all he wants is to stand in the street where Eliza lives—it is also the crucial representation of Shaw’s insistence that Freddy and Eliza marry after the story’s conclusion. By making sure that Freddy stays in the story and looks after Eliza in her journey from Higgins’s house to Mrs. Higgins’s, Lerner and Loewe guarantee that we know that an Eliza-Higgins union is not inevitable, even if that is where the plot’s main point of tension lies.

“The Servants’ Chorus” is one of the show’s most ingenious numbers. It allows Lerner and Loewe to give momentum to the series of lessons for Eliza—each lesson is punctuated by a single refrain, played a semitone higher and faster each time. The relationship between song and dialogue is at its most fluid here: the verses begin with one bar of introduction to give the servants their pitches, and the music fades out in every case to the middle of Higgins’s next lesson, without musical closure. This was planned from the beginning: Outlines 1–4 all mention a montage of lessons. In Outline 4, the chorus appears both before and after “Just You Wait”; it is surely better that in the published version it comes afterwards only and propels us without interruption to “The Rain in Spain.”

The content and number of verses were decided late in the day. The rehearsal script indicates five places during the scene where the chorus was to be sung, but no lyrics for the number are included. Unusually, there are two copies of the number in Loewe’s hand: one in the Loewe Collection, and one in the Warner-Chappell Collection. Both plot out the first verse, though only the first page of the Warner-Chappell manuscript is in Loewe’s hand, and even then, Rittmann

wrote both the “Moderato” tempo marking and the whole of the second page. The Loewe Collection version is in G minor—the key in which it was orchestrated and published—and is fluently written. At the top of the first page, Loewe wrote “Alan—Call Moss: How many verses?” while at the bottom of the final page he has indicated: “Each verse ½ tone higher into ‘Rain in Spain.’” That the lyric was written in pen (uniquely among the Loewe manuscripts) might, as Geoffrey Block has proposed, suggest that it was therefore a late addition, because the use of ink is a more final gesture than the more normal pencil.

21

On the other hand, it is unclear which of the two manuscripts came first. After all, the Warner-Chappell version is in A minor, whereas the composer appears to have known that the final key would be G minor when writing the Loewe Collection version. Then again, that the Loewe Collection manuscript is entirely in the composer’s hand and the Warner-Chappell one is in a mixture of both his and Rittmann’s could point toward the latter being a subsequent version. At the bottom of the second page of the Warner-Chappell score is a message in an unknown hand indicating the verses and the keys they were to be written in next to them.

22

On the reverse, Loewe himself wrote more specific directions:

(1). As is (Cup of tea) G min

(2). 3 (blackout) Higgins continues 4-5-6 A flat min

(3). As is. 11th bar “How kind of you” (Orch.) blend to Higg.

(4). As is (Rain in Spain) A min.

These slightly cryptic fragments indicate what dialogue the verses are to fade into, with a special case of enjambment in the second chorus where the servants end by counting the hours of the morning at which Higgins is working (“One a.m., / Two a.m. / Three…”) followed by a quick blackout, after which Higgins continues the numbers by counting marbles into Eliza’s mouth (“Four, five, six marbles”).

Inserted into the score is a typed lyric sheet with four verses of the song. The published version has only three, but originally the following was the penultimate verse:

Stop, Professor Higgins!

Stop, Professor Higgins!

Stop we pray

Or any day

You’ll drop, Professor Higgins!

Hours fly!

Weeks go by …!

Keith Garebian writes that the servants “sympathise with Higgins rather than Eliza” in this number, but this early lyric (which is also used in the copyist’s piano-vocal score and Bennett’s orchestration) shows that it was originally more sympathetic to him than it is in its published form.

23

In the cut verse, the servants encourage Higgins to “stop before he drops”; but Lerner and Loewe left in the far-from-sympathetic final verse, which tells him to “quit” before the servants do.

The climax of the lessons sequence is, of course, “The Rain in Spain.” As Geoffrey Block has noted, there is a discrepancy between Lerner’s account of when it was written and Harrison’s autobiography, which names the song as one of those played by Lerner and Loewe for him at their initial meeting.

24

The actor claimed that at the time this was “the only number that really whizzed along,” adding that it was “about all they had in the way of show tunes, and it was obviously a great one.” Lerner, by contrast, says that the song was written later, during auditions in the summer of 1955. It was supposedly their only “unexpected visitation from the muses” and came as the result of Lerner’s idea to write a song in which Eliza can now speak correctly all the things she has done wrong before. Since her main problem is with the letter A, Lerner suggested calling it “The Rain in Spain.” This inspired Loewe to write a tango, taking only ten minutes to finish it. Since Outline 1 mentions both the song and its function in quite a lot of detail—“In the joy of the moment the line turns into a song, a Spanish one-step, which the three sing and dance jubilantly”—Lerner’s chronology is clearly inaccurate. Furthermore, he obscures the chronological relationship between “The Servants’ Chorus” and “The Rain in Spain,” even though the latter was clearly one of the earliest songs and the former was one of the last to be finished.

Still, the ease that Lerner associates with its creation is upheld by the sources. Loewe’s autograph score reproduces the vocal section of the song in its final version, though the dance music is not included, and as before, it is a fair copy, not an “original” manuscript. Although there are lines on the second and fourth pages where the music has been crossed out, these are the result of a slip of the pencil (p. 2) and perhaps the need to reuse manuscript paper that already had a small sketch of a different piece of music on it (p. 4, which has two-and-a-half bars of unrelated material crossed out at the top) rather than showing Loewe’s evolving ideas. In most respects, the voicing is too well worked out and the writing too neat and fluent to allow us to consider this the initial result of Loewe’s thought patterns. Once more, Rittmann composed the dance music. A negative photocopy of her piano score for the dance has survived, though the original pencil copy has not.

25

She indicates the righthand part only for the first fifteen bars, which are a continuation of

the “Rain in Spain” music, but from bar 16 on (the “Jota” section from the change to triple time) she writes out the whole thing, including the final shout of “Olé” from Higgins, Eliza, and Pickering. Together, Loewe and Rittmann provided Bennett with all the information he needed to orchestrate the number, and his autograph score is clear of changes.

Brief mention is due to the scene change music (No. 10a) that follows “I Could Have Danced” and leads quickly into “The Ascot Gavotte.” This little snatch of music for solo trumpet takes up only two bars and eight notes (

ex. 6.4

) and was written by Lang on a blank system in the middle of Bennett’s “I Could Have Danced” full score (in line with the final bars of that song). But there can be no doubt that Loewe is responsible for the theme, because it is an exact copy of the first two bars of the introduction of his 1941 song “The Son of the Wooden Soldier,” written with lyricist John W. Bratton (

ex. 6.5

).

26

Piecing together the score for the Ascot scene was complicated. The autograph score contained in the Loewe Collection is so brief that it does indeed seem to be the basis for the copyist’s arrangements.

27

Loewe provided a three-page score containing a full verse of the song, completely harmonized. However, Rittmann stepped in to flesh out the number to its familiar proportions, and there are surviving fragments of her manuscripts for the dance section, the introduction, and the music that closes the scene (including the brief reprise).

28

Dance pianist Freda Miller’s copy of the copyist’s score is fully annotated to show how Rittmann’s “Gavotte Dance” music was to be fitted into

the middle of the sung verses. A separate photocopy of Rittmann’s “Intro to Gavotte” manuscript, marked “Freda” at the top, shows a new, longer introduction for the final version,

29

as well as the original lyric, which had an extra verse and different words for the reprise (see

appendix 4

).

30

A lyric sheet from the Warner-Chappell Collection also indicates that originally, Eliza’s shocking cry to close the scene was “Come on, Dover! Get the bloody lead out!”

31

This seems to have been kept into the rehearsal period: the copyist’s choral score and conductor’s score both contain two verses of the song, even after the new introduction and dance section had been added.

32

Bennett’s full score also follows this version, but Lang intervened by adding two pages to end the first sounding of the song and thereby complete the number.

Ex. 6.4. No. 10a, Scene Change.

Ex. 6.5. “The Son of the Wooden Soldier.”