Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (16 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

Consistent with the changes made to act 1, scene 5, the relationship between Eliza and Doolittle is much darker in the rehearsal version of the Ascot scene too, even though he is physically absent. Eliza originally had a long speech (deriving from

Pygmalion

), dealing with the news that her father is an alcoholic (

RS

, 1-7-58). Mrs. Eynsford Hill expresses sympathy, but Eliza replies that “it never did him no harm” and assures her that he did not “keep it up regular.” Doolittle only did it “on the burst … from time to time,” and Eliza points out that he was “always more agreeable” afterwards. Her mother would send him out to drink himself happy if he was out of work. Eliza’s motto is simply that “if a man has a bit of conscience, it always takes him when he’s sober. … A drop of booze just takes that off and makes him happy.” This statement represents Shaw at his most acute.

44

The comment not only exposes Eliza’s social status, it also gives a shocking insight into the emotional conditions in which she was raised.

PS

removes this element of the scene, retaining reference to Doolittle’s drinking habits only in passing for a joke (“Drank! My word! Something chronic,” 106). In consequence,

PS

maintains light comedy throughout the Ascot scene rather than adding new insights.

Doolittle’s final appearance, in the Covent Garden scene in act 2, was also changed, specifically during his last exchange with Eliza. This confrontation is an invention of the musical, though it does have an equivalent in

Pygmalion

through Doolittle’s presence in the final scene. (In the play, Freddy, Mrs. Higgins, Pickering, and Eliza all depart for his wedding; crucially, Eliza does not attend the ceremony in the musical, and Lerner implies a final rift between them.) During rehearsals, Lerner excised several lines showing the “philosophical” Doolittle. He says that he was “free” and “happy” and didn’t

want to be interfered with. He had no relatives, but now he has “fifty, and not a decent week’s wages among the lot of them.” He used to live for himself, but now he’s “middle class” and has to “live for others.” He concludes: “The next one to touch me will be your blasted professor. I’ll have to learn to speak middle-class language from him instead of speaking proper English” (

RS

, 2-3-17). This is an interesting speech that depicts Doolittle’s fate as part of a wider social commentary within the show; his previous life was one of freedom, whereas financial security has entailed social burden—a direct contradiction to Higgins’s philosophy, where the Cockney dialect binds the working classes and clear diction facilitates social liberation. The other addition to the speech follows the news that Doolittle is to be married to “Eliza’s stepmother”: “She wouldn’t have married me before if she’d had six children by me. But now I am respectable. Now she wants to be respectable. Middle-class morality claims its victims” (

RS

, 2-3-17). Again, Doolittle reinforces the idea of his social shift as being something imprisoning rather than giving him an opportunity, describing himself as a “victim” and making it clear that social respectability (not love or affection) is the reason for the marriage.

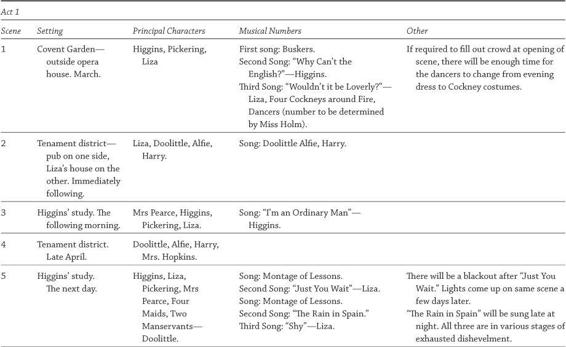

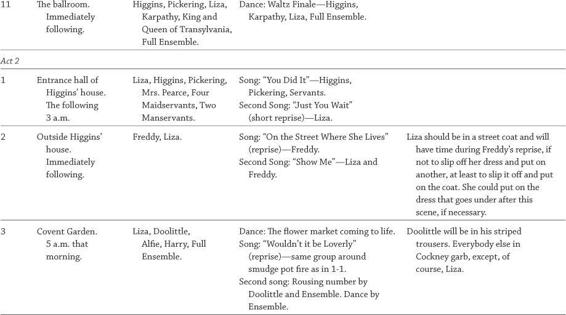

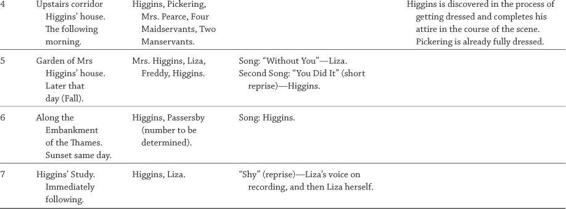

Table 3.5.

Outline 4

The all-important battle between Higgins and Eliza was intensified throughout the script during rehearsals. In act 1, scene 3, Lerner added several lines after Mrs. Pearce’s question about whether Eliza is to be paid for taking part in the experiment. Higgins claims that Eliza will “only drink if you give her money,” much to her indignation; she appeals to Pickering, who comes to her defense and asks whether it occurs to Higgins that Eliza “has some feelings.” The Professor replies that he does not think she has “any feelings that we need bother about,” but Mrs. Pearce interjects and asks him to “look ahead a little” (

PS

, 30–31). Yet again, these lines show Lerner going back to Shaw’s text to add nuance to the musical.

45

Higgins’s character is further developed in his song, “I’m an Ordinary Man.” The dialogue leading into the number was changed quite substantially during the rehearsal period. In particular, his original line, “Do I look like the kind of person who roams about anxiously searching for some woman to upset his life?” (

RS

, 1-3-25), is noticeable in the way that Higgins seems to reject the idea of having a female lover at all. The replacement is less clear-cut, relating a history of relationships with women that have gone badly as the reason for his bachelorhood: “I find that the moment I let a woman make friends with me she becomes jealous, exacting, suspicious and a damned nuisance. I find that the moment I let myself become friends with a woman, I become selfish and tyrannical. So here I am, a confirmed old bachelor, and

likely to remain so” (

PS

, 35). Unusually, this is an example of

PS

making Higgins’s possible status as a lover more tantalizing, rather than more obscure.

The revised speech is quite an improvement, because Higgins bares his soul in an unprecedented fashion, and thereby reveals his emotional repression: his relations with the opposite sex have been a disaster, and in his way he has been damaged by them. As before, Lerner reinstates several lines from Shaw. But he still omits the following statement of Higgins’s: “You see, she’ll be a pupil; and teaching would be impossible unless pupils were sacred. I’ve taught scores of American millionairesses how to speak English: the best looking women in the world. I’m seasoned. They might as well be blocks of wood.

I

might as well be a block of wood.”

46

It is no accident that these lines were omitted from

My Fair Lady

: Lerner’s Higgins cannot exaggerate his immunity to the opposite sex if the musical’s ambiguous treatment of the Higgins-Eliza relationship is to be effective.

Two scenes later, the subject of Higgins’s relationship with Eliza is again discussed openly, this time by Doolittle just before he departs the house: “I don’t know what your intentions is, Governor, but if you’ll take my advice you’ll marry Eliza while she’s young. If you don’t, you’ll be sorry for it after. But better her than you, because you’re a man and she’s only a woman and don’t know how to be happy anyhow” (

RS

, 1-5-36, partly based on

Pygmalion

, 56). This was later altered to a shorter speech in which Doolittle advises Higgins simply to give Eliza “a few licks of the strap” if he has any trouble with her. Originally, however, Doolittle explicitly states his assumption that Higgins desires Eliza. Such a line seems oddly out of place in the musical, but it makes sense in the context of other comments from

RS

, in which a union between Higgins and Eliza seems almost inevitable. So different was its tone, in fact, that Higgins does not even react to Doolittle’s comment about marrying Eliza. That Lerner changed this only during rehearsals suggests that the shift to romantic ambiguity was not yet complete.

The next person to inquire about Higgins’s business with Eliza is his mother. In the original act 1, scene 6, Higgins and his mother discuss the experiment outside the race course; but the final version has Pickering in Higgins’s place. The most surprising part of the

RS

version of the exchange is when Mrs. Higgins asks, “Henry, do you know what you would do if you really loved me?” and Higgins replies, “Marry, I suppose” (

RS

, 1-6-51). It seems that even during the rehearsal period, the subject of Higgins’s possible matrimony was still openly discussed between the two characters, positing the Professor more overtly as a romantic lead. Later in the scene, Mrs. Higgins raises the issue again, asking where Eliza lives and on what terms she lives there (

RS

, 1-6-51). Higgins replies that she is “very useful,” “knows where things are,”

and “remembers my appointments.” But, he concedes, “she’s there to be worked at.” Higgins confesses it’s his “most absorbing experiment” to date and that he thinks about Eliza “even in my sleep.” An element of this exchange was brought back for the film version of the show, in which a scene is added outside Ascot after the race and Higgins admits that he and Pickering are “at it from morning until night … teaching Eliza, talking to Eliza, listening to Eliza, dressing Eliza…” But in addition, Higgins tells us (in

RS

alone) that “Even in my sleep I’m thinking about the girl and her confounded vowels and consonants. I’m worn out thinking about her, and watching her lips and her teeth and her tongue, not to mention her soul, which is the quaintest of the lot.” Most of this comes from Shaw, but—significantly—Lerner replaces Shaw’s “As if I ever stop thinking about the girl” with “Even in my sleep…”

47

That Higgins’s nights are absorbed in thinking about Eliza, coupled with the sensuous language he uses to talk about her lips, teeth, and tongue, signifies an infatuation that does not stop at intellectual intrigue.

The replacement scene still touches lightly on the status of the Higgins-Eliza relationship, but Pickering is instantly dismissive of the idea of romance between the two when Mrs. Higgins asks if it is a love affair: “Heavens no! She’s a flower girl. He picked her up off the kerbstone” (72). This encounter increases the ambiguity of the relationship between Eliza and Higgins because Pickering, who lives with both of them, does not seem to have detected a romance. Nevertheless, his comment does not rule anything out, muddying the waters brilliantly.

Another character whose personality was modified is Freddy. His main function in the Ascot scene is to provide Eliza with the bet on Dover, the horse that will bring about the memorable climax to the sequence. In

PS

he does this fairly discreetly, merely informing Eliza that he has a bet and offering it to her. However, in

RS

he is given a prominent entrance (

RS

, 1-7-55). When he arrives holding a ticket, his mother pounces on him and says: “You know you can’t afford it, dear.” He replies that he “had to” because the odds were “too good to resist.” In this original formulation, Freddy is depicted as a compulsive gambler. As the musical evolved, Freddy increasingly became the polar opposite of Higgins, so that the Eliza-Higgins-Freddy love triangle had a stronger dynamic. Arguably, the idea that Freddy is the sort of person who gambles for thrills and cannot resist the odds on Dover makes him a risk taker and a more masculine, virile character. Therefore, it is easy to see why Lerner removed this element of Freddy’s personality and made him into a faithful but dull lover for Eliza.