Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (15 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

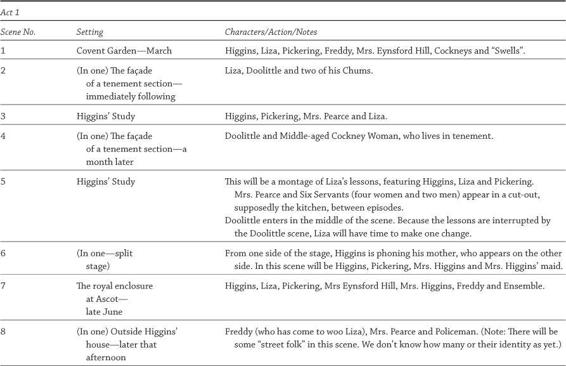

Although the first scene in Outline 3 has been moved back to Covent Garden from Limehouse and several of the other scenes are in a familiar form, scene 6 still has a telephone call between Higgins and his mother that does not appear in the published show or in

Pygmalion

. Scene 8 has a Policeman who was eventually not included, and scene 9 still contains a scene in which Higgins persuades Eliza to continue with the experiment, followed by the ballet which stayed in the show until New Haven. Act 2, scene 4 is “undetermined”; apparently, Lerner had not yet finalized the scene where Higgins and Pickering discover Eliza’s disappearance and resolve to track her down. This part of the story is not shown in the

Pygmalion

play or film and is a key example of Lerner “filling in the action” between the play’s acts. The next scene is also interesting in that it appears to preserve the action of

Pygmalion

by including Doolittle, who departs from the show after the return to Covent Garden in the published version, and Pickering, whose final appearance in

Fair Lady

is in scene 4. The Colonel also appears in the ensuing scene, along with some “Street Folk”; the purpose of this tableau is unclear, however, though the final scene is in its familiar form. In summary, Outline 3 moves us much closer to the definitive structure of the musical, but several scenes were still in a different form. Of particular relevance is the scene of Higgins’s near-“seduction” of Eliza in act 1, when he persuades her to continue with the experiment: this shows that Lerner was continuing to overplay the Higgins-Eliza relationship, even though as a whole his plan moves back toward

Pygmalion

as a model.

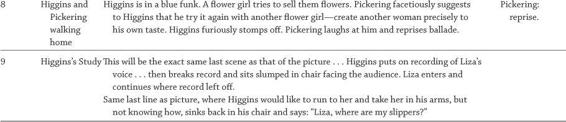

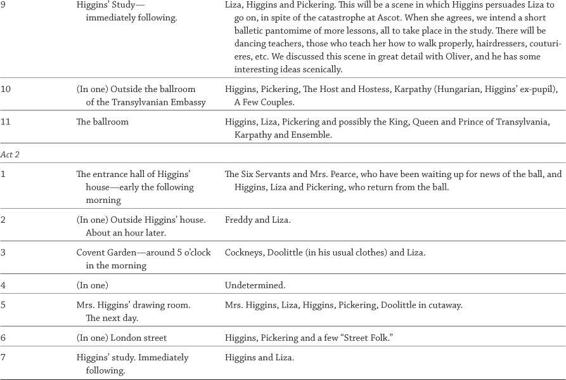

Finally, Outline 4 (

table 3.5

) comes from the papers (housed in the New York Public Library) of the show’s choreographer, Hanya Holm. It undoubtedly postdates her agreement to create the dances for the show because it includes a reference to “Miss Holm.” This places it somewhere between late September 1955 and the rehearsal period in January 1956, probably nearer the former than the latter. By this stage the structure of the show was much more strongly in place. Reflecting this, Outline 4 is very thorough in mentioning the locations, times, musical numbers, and characters involved in each scene, in contrast to the previous outlines.

At first glance, it may seem that Outline 4 represents the published show, but there are several important additions and omissions. At the start, there is reference to a song for the Buskers. Assuming that this is not the orchestral “Opening” that depicts Covent Garden after the Overture, this could have been an additional scene-setting song in the style of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” Neither of Doolittle’s songs has a title, hinting

they had not yet been written, and scene 4 does not have the reprise of his first number either. Scene 5 has a “montage of lessons” song (which became “Poor Professor Higgins”) both before and after “Just You Wait,” whereas it only appears after Eliza’s song in the published version. Another obvious difference is that “I Could Have Danced All Night” had not yet been written and an earlier song, “Shy,” was in its place. On the other hand, scene 6 is similar to the published script, except that Higgins appears to have been the person talking to his mother outside the racecourse, rather than Pickering; obviously, the latter character benefited from an extra moment of humor in the final show, especially in light of the extent to which Pickering’s role had been reduced from the initial outlines.

Table 3.4.

Outline 3

Lord and Lady Boxley (scene 7) later became Lord and Lady Boxington, and in this version the Policeman in scene 8 has been replaced by possible Street Strollers. The sequence of musical numbers in scene 9 was still in its original form, unsurprisingly, but the next few scenes seem to be roughly in their published state. A crucial exception is Liza’s apparent exclusion from the group reprise of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” Scene 4 is now in place, with the exception of “A Hymn to Him” (which was added much later), and only the location of scene 5 is unfamiliar: this outline has it in Mrs. Higgins’s garden, rather than her conservatory (in the final show). It is also worth noting that the reprise of “You Did It,” with which Higgins interrupts Eliza’s “Without You,” is already fixed and not a late addition as Lerner claimed in his memoir. The setting for Higgins’s final song is also unfamiliar: the location by the Thames is still an anomaly since, as noted above, a scene in Higgins’s house cannot “immediately follow” one on the Embankment because the two are geographically displaced. The final scene is crowned by a reprise of “Shy” rather than “I Could Have Danced All Night” because the latter had not yet been written. It is interesting to note that this aspect of the structure of the show—the reprisal of Eliza’s first-act putative “love song”—was already firmed up. One might easily have thought that the last-minute return to the “I Could Have Danced” music was a way of bringing the curtain down on what the composer and lyricist guessed could be the show’s hit song, but gesture was clearly the highest priority all along. In conclusion, Outline 4 reveals that although the musical follows

Pygmalion

quite closely, many factors had to be created or changed along the way, as the numerous differences between this late outline and the published script demonstrate. By extension, this shows how deliberate, considered, and thoughtfully contrived the piece is.

The main text to be considered in this section is the document labeled “Rehearsal Script” in Herman Levin’s papers.

39

There are a couple of hundred differences between the musical’s identified rehearsal script and the published script, and these afford an insight into the last-minute polishing done by Lerner and the director, Moss Hart, during the rehearsal period. Curiously, the authorship of Lerner’s book has sometimes been called into question, with the suggestion that Moss Hart was in effect the co-author. For instance, his wife, Kitty Carlisle Hart, mentions that Lerner and Hart “went to Atlantic City for a week to work on the script” and adds that when she asked Hart about it, he replied that “he was hired as the director, and the fact that he was a writer-director didn’t make any difference.” On the other hand, Steven Bach reports that Lerner’s production associate Stone Widney—who was present during the writing and rehearsal stages—remembered Hart contributing “very little to the book.” No evidence remains in Moss Hart’s papers in Wisconsin of the director’s additions either, and the issue cannot easily be resolved. Therefore, for the purposes of this book Lerner is referred to as the author of the script, even though there is no doubt that Hart’s contributions were vital to its success.

40

Diction seems to be one of the main concerns of Lerner’s revision of the script. Often he changed just a couple of words or the word order to make it as convincing as possible, especially in the cockney scenes. For example, Eliza’s “Two bunches of violets trod into the mud” (rehearsal script [hereafter

RS

], 1-1-1) becomes simply “ … trod in the mud” (published script [

PS

], 2).

41

This is a small change, but it makes the line sound shorter and more abrupt, as well as introducing a grammatical mistake (Shaw’s

Pygmalion

has “into”).

42

Rather than detailing all such changes, however, this section deals mainly with the ways in which the differences between the rehearsal and published scripts had implications for the central relationships in the piece.

The biggest changes made during rehearsals were to the part of Alfred Doolittle, Eliza’s father, one of the show’s most vibrant characters. His relationships to the other characters shifted in focus, and some of the darker aspects of his personality were obscured. For example:

RS

(1-2-13)

DOOLITTLE

: Well, I’m willing to marry her. It’s me that suffers by it. I’ve no hold on her. I got to be agreeable to her. I got to give her presents. I got to buy her clothes something sinful. I’m a slave to that woman, Eliza. Just because I’m not her lawful husband. And she knows it, too. Catch her marrying me! Come on, Eliza. Slip your father half a crown to go home on. An unmarried man has to deaden his senses much more than a married one.

PS

(17)

DOOLITTLE

: Well, I’m willing to marry her. It’s me that suffers by it. I’m a slave to that woman, Eliza. Just because I ain’t her lawful husband.

[Lovably]

Come on, Eliza. Slip your father half a crown to go home on.

The first extract gives a sense of the extent of Doolittle’s misery at not being married to the woman with whom he lives. He says that he has no hold over her, and that he is obliged to buy her presents in order to keep her, because he has no legal rights. His final line (“An unmarried man…”) is tinged with a melancholy that we might not normally associate with the jovial “Lerner” Doolittle, but it is absolutely consistent with Shaw’s arguably more elegiac Doolittle. The replacement speech still contains reference to “slavery,” but it is not explained, losing the opportunity for a darker moment.

The subject of Doolittle’s relationships, especially with Eliza’s current “stepmother,” was originally discussed more explicitly. Particularly important is the indication in

RS

that Eliza is aware that her parents were not married: when Mrs. Pearce asks Eliza about her parents, she replies, “I ain’t got no mother. Her that turned me out was my sixth stepmother, and my father isn’t a marrying sort of man if you know what I mean” (

RS

, 1-3-23). Lerner simplified this to “I ain’t got no parents” (

PS

, 30), almost as if she is simply an orphan, yet the original is more revealing, because we learn about Eliza’s insecure upbringing. It also discloses that she is aware her parents were not married, something her father later claims (to Pickering and Higgins, albeit in

RS

only) that she does not know. Again, the cut line derives from Shaw, who mentions Eliza’s “sixth stepmother” but does not have the comment about Doolittle not being “a marrying sort of man.”

43

The encounter (a couple of scenes later) between Higgins and Doolittle is white-hot. Deciding how to carve this scene must have been quite a challenge for Lerner: money changes hands for Eliza and Doolittle “sells” his daughter, which paints him in an unpleasant light, yet he has to remain a

likeable

rogue.

One theme that Lerner originally explored more extensively was the “undeserving poor,” a label that Doolittle gives himself early on in the scene. An example is the line “They charge me just the same for everything as they charge the deserving” (

RS

, 1-5-33), which was later removed; here, Doolittle explains why he needs money. Later, he rejects Higgins’s offer to train him to be a preacher: “Not me, Governor, thank you kindly … it’s a dog’s life any way you look at it. Undeserving poverty’s my line” (

RS

, 1-5-34, derived from

Pygmalion

, 55). Soon afterwards, when Pickering says that he assumes Doolittle was married to Eliza’s mother and is firmly put straight on the subject, Doolittle adds: “No, [i]t’s only the middle class way. My way has always been the undeserving way. But don’t say nothing to Eliza. She don’t know” (

RS

, 1-5-35). This reintroduces the reality of Eliza’s background hinted at in the previous scene, and underlines the fact that she is illegitimate while more generally showing that she was brought up with a different sense of morality than the place in which she now finds herself (the additions are not from Shaw).