Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) (11 page)

Read Loverly:The Life and Times of My Fair Lady (Broadway Legacies) Online

Authors: Dominic McHugh

Tags: #The Life And Times Of My Fair Lady

Casting continued apace as, among others, Levin hired Philippa Bevans as Mrs. Pearce on November 15; Rod McLennan as a member of the ensemble (he went on to play a Bystander in the opening scene, as well as Jamie and the Ambassador) and understudy on December 5; Olive Reeves-Smith as Mrs. Hopkins and Lady Boxington on December 9; and Viola Roache (as Mrs. Eynsford-Hill and Mrs. Higgins’s understudy) on December 12 (the date when Robert Coote’s final contract was also signed).

136

Richard Maney was hired as the company’s Press Agent on November 26, commencing on January 9, 1956; he would be an active participant throughout the show’s original Broadway run, as a lengthy folder of material in Levin’s papers proves.

137

An agreement was drawn up with Trude Rittman on November 30 to be the Dance Arranger, and on December 2, Ernest Adler was signed on to create “all hair stylings and coiffures” for the production.

138

The signing of Rittman was especially important: she had arranged the dance music for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Oklahoma!, Carousel

, and

South Pacific

, and the “Small House of Uncle Thomas” ballet from

The King and I

. After working together on

Brigadoon

, Loewe brought her in again for

Paint Your Wagon

as well as the later stage adaptation of

Gigi

(1973). In

Fair Lady

, she was so completely trusted by the composer that he allowed her to create the lengthy choreographic sequences without his intervention, nor was her work confined merely to the dance music.

139

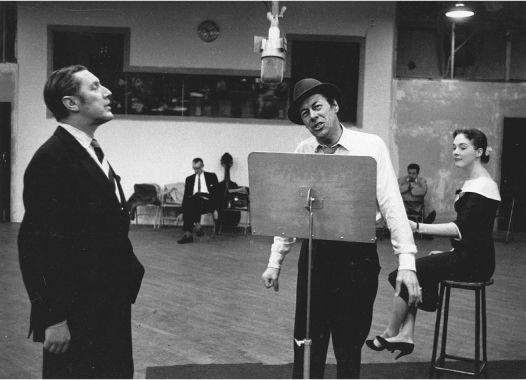

The recording of the original cast album, with

(left

to

right)

Robert Coote, Rex Harrison, and Julie Andrews (Photofest/Columbia Records)

Meanwhile, although Cecil Beaton had successfully ordered the costumes he required for Rex Harrison, there was a question of how to get them from England to the United States. Beaton felt it was awkward for him to ask Harrison to take them there himself as a favor and suggested that Levin should ask the actor.

140

Levin replied that since Harrison was traveling by plane, this was impossible, and asked whether it would be possible to send them by “some other means, perhaps air express or air freight?”

141

The producer also made a suggestion regarding Julie Andrews’s hair: “It occurs to me that it might be a good idea if it were made an auburn shade.” Within the following week the problem with Harrison’s clothes was solved, as the actor himself volunteered to carry them in his luggage; the producer wrote to Harrison to thank him and to promise to pay the excess baggage, which came to around $450.

142

To Beaton, Levin also followed up his comment about Andrews’s hair: “My idea was only a suggestion,” he informed Beaton. “I gather from your letter that you have brightened the tone of her hair considerably. I thought that her own hair seemed rather drab.”

143

During December, Levin also approached several companies regarding the construction of the scenery for the show. The contract went to the Nolan Brothers of West Twenty-fourth Street, who provided the sets for $65,000.

144

The year’s correspondence ends with letters from Levin to the key actors in which “the

Pygmalion

musical” is finally referred to as

My Fair Lady

; that to Robert Coote on December 28 appears to be the earliest example.

145

The question of what to call the show was one of the most important decisions to be made. Lerner addresses the issue in his autobiography, saying that the early suggestions

Liza

and

My Lady Liza

“went to their final resting places in the trash basket” because “it would have seemed peculiar for the marquee to read: ‘Rex Harrison in

Liza.

’”

146

He claims that

My Fair Lady

was considered and discarded because “it sounded like an operetta” and that Loewe liked

Fanfaroon

as a title “primarily I believe because it reminded him of

Brigadoon.” Come to the Ball

was also considered. Later, Lerner claims that “toward the second week of rehearsal,” Levin came to the theater and demanded that Lerner, Loewe, and Hart decide on a title, at which point they agreed to choose

My Fair Lady

because it was the one they disliked the least.

147

But this chronology is difficult to corroborate with documentary evidence. During the autumn of 1955, the show is typically referred to as

My Lady Liza

, and most of the contracts refer to this as the title. Then on November 29 Lerner wrote a long letter to Harrison, in which he mentioned the issue of the title in the postscript: “

Fanfaroon

has not been abandoned, although there is stiff opposition,” he wrote. “But

My Lady Liza

will definitely not be it. I know this will break your heart, because you seem so terribly fond of it.”

148

Although Lerner claims in

The Street Where I Live

that the final decision was made during the second week of rehearsals, in fact it must have happened between December 16 and 28.

149

My Fair Lady

it was to be, and on December 30 Levin sent the record producer Goddard Lieberson an outline of the billing sheet for the show for use on the cover of the Original Cast Album with the new title stamped proudly across the middle.

150

Not surprisingly, the primary documentary sources for the remainder of the time leading up to the opening night on Broadway are less detailed than that for the preceding months. With the cast and crew in the same place for most of the time between the start of rehearsals (January 3), the opening night in New Haven (February 4), the Philadelphia tryout (February 15) and the Broadway opening (March 15), there was little need for written correspondence between the key players. This means that we have to fall back on the memoirs of figures such as Lerner, Andrews, Harrison, Holloway, Kitty Carlisle Hart (the director’s wife), and Doris Shapiro (Lerner’s assistant) to fill in many of the gaps, as well as newspaper reports and playbills. Nevertheless,

a number of letters from this period remain, because Levin kept things ticking over while the show was being staged and rehearsed.

On January 4, he wrote to Laurie Evans in London to tell him that “Rex arrived in good shape; rehearsals started yesterday; and everyone is working hard.”

151

The cast was working upstairs at the New Amsterdam Roof, 214 West Forty-second Street in New York for the first four weeks until embarking for New Haven at the end of the month.

152

The entire ensemble gathered onstage for the first time on January 3. Lerner tells us that “Around the edges of the stage Moss had arranged an exhibition of sketches of the scenery and the costumes, and the press was allowed in to do their first-day interviews. … The cast read the script aloud, with Moss reading the stage directions. Whenever they came to a song, Fritz and I performed it. After the first act the enthusiasm was high.”

153

The exception was Rex Harrison, who felt that the character of Higgins had been put too much into the background in the second act. The solution was to add the song “A Hymn to Him,” better known as “Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?” Supposedly, the inspiration for this song came from Harrison himself, while walking down Fifth Avenue during the rehearsal period. Lerner reports that they had been “reviewing our past marital and emotional difficulties and his present one. … Suddenly, he had stopped and said in a loud voice that attracted a good bit of attention: ‘Alan! Wouldn’t it be marvelous if we were homosexuals?!’ I said that I did not think that was the solution and we walked on. But it stuck in my mind and by the time I reached the Pierre I had the idea for ‘Why Can’t a Woman Be More Like a Man?’”

154

The lyricist adds that it was finished by the end of the eighth day of rehearsals.

Hart’s rehearsal schedule was distinctive, incorporating an afternoon and evening schedule to leave the mornings free for other aspects of the production process. Andrews reports that “We began working every day at 2:00 p.m., took a break for dinner at 5:30 p.m., and then reassembled from 7:00 until 11:00 in the evening. Stanley Holloway and I kept up the British tradition of a cup of tea at 4:00 in the afternoon, and soon everyone was enjoying that welcome little break.”

155

Lerner explains that the choice of this rehearsal schedule was deliberate: “Most directors like to begin in the morning at ten o’clock and rehearse until one or one thirty, returning at three and continuing until seven. Moss did not. He felt that by the end of the day the cast was usually so tired that little was accomplished in the last two hours,” hence the decision to start at 2 p.m.

156

Another oft-repeated story about the show is that during rehearsals, Harrison kept brandishing a Penguin edition of Shaw’s

Pygmalion

and referred to it “at least four times a day, if a speech did not seem right to him,” according to Lerner. He would invariably cry out,

“Where’s my Penguin?” and compare the text of the show to that of the play. After a week, Lerner’s response was to go to a taxidermist and purchase a stuffed penguin, which he had rolled out the next time Harrison asked the question. “From that moment on, he never mentioned the Penguin again and kept the stuffed edition in his dressing room as a mascot throughout the run of the production.”

157

It was not merely the nervous Harrison who made life challenging for Hart and Lerner during this time; the inexperience of Julie Andrews as an actress in a substantial piece started to cause problems, too. After two weeks of rehearsals “Moss decided drastic assistance was needed. He closed down rehearsals for two days and spent them alone with Julie.”

158

Andrews herself adds that “it became obvious … that I was hopelessly out of my depth as Eliza Doolittle. … And that’s where Moss’s humanity came in. … [He] decided … to dismiss the company for forty-eight hours and to work solely with me. … For those two days … [we] hammered through each scene—everything from Eliza’s entrance, her screaming and yelling, to her transformation into a lady at the end of the play. Moss bullied, cajoled scolded, and encouraged.

159

Lerner adds: “On Monday morning when rehearsals began again with the full company, Julie was well on her way to becoming Eliza Doolittle.”

160

Though Andrews was now feeling more confident, Stanley Holloway in turn became unhappy that insufficient time was being spent on rehearsing his character, but on confronting the director with this issue he was told by Hart, “Now look, Stanley. I am rehearsing a girl who has never played a major role in her life, and an actor who has never sung on the stage in his life. You have done both. If you feel neglected it is a compliment.”

161

The actor was mollified.

One important job to be done during this time was for the show to be orchestrated. On January 5 Levin signed a contract with the arranger Guido Tutrinoli and three days later another with Robert Russell Bennett, who orchestrated the show with Phil Lang (and the “ghost” orchestrator, Jack Mason).

162

It was Bennett who insisted that Lang be credited with the orchestrations along with himself, writing a letter to Levin on February 11 specifically asking it as “a favor.”

163

Other things to be taken care of included ordering floral arrangements for the show from the Decorative Plant Corporation, and items such as necklaces and bracelets from Coro Jewelry, paying for the costumes Beaton had ordered in London, and finishing off the costume order with the Helene Pons Studio.

164

After spending January rehearsing the show in New York, the company moved to New Haven, where the New Haven Jewish Community Center had been hired for rehearsals between January 30 and February 1.

165

Over at the Shubert Theatre, Biff Liff, the stage manager, “wrestled with the scenery,”

and although chaos ensued with the complicated sets, they were in sufficient order by Wednesday night to have a technical run-through.

166

It was complete by Friday, and the orchestra arrived in the pit for the first time—“and blew Rex sky high,” according to Lerner.

167

The actor’s inexperience as a singer meant that he was extremely intimidated by the overwhelming sound of the orchestra, and Hart promised he could rehearse alone with the orchestra the following afternoon.

“But his terror of the orchestra did not abate,” Lerner continues. “Late that afternoon with the house sold out and a fierce blizzard blowing, Rex announced that under no circumstances would he go on that night.” The performance was cancelled, and announcements were made on the local radio stations. However, “by six o’clock that evening hundreds of people had braved the snow and were already queuing up at the box office. The house manager was livid. He swore to us all that he would tell the world the truth. … About an hour and a half before what would have been curtain time Rex’s agent arrived from New York. … No matter what happened that evening on stage, he said, Rex damn well had to go on. Fear of the consequences must have overshadowed his fear of the orchestra because one hour before curtain time, Rex recanted.”

168

So in the end, the show did begin that night of February 4 at 8:40 p.m. Although there were some technical difficulties with the turntables and curtains, Lerner says that “the total effect was stunning and when the curtain came down the audience stood up and cheered.”

169

Variety

reviewed the show in its New Haven incarnation and reflected the reception that Lerner indicated, stating: “

My Fair Lady

is going to be a whale of a show … [It] contains enough smash potential to assure it a high place on the list of Broadway prospects.”

170

Every aspect of the production came in for praise.