Kate Berridge (37 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Her public image: Formal portrait of Madame Tussaud by Paul Fischer, 1845

A private view: Marie Tussaud by Francis Tussaud

It never seemed to be for herself but always for the fruits of her hard labour that she attracted the attention of a man. For, as well as there being an avaricious husband circling around her success, Marie's exhibition came into the sights of the American showman Phineas Taylor Barnum, whose beady eye for hits quickly fell on her gem. Barnum had made his English debut in Liverpool, where he caused a sensation with Tom Thumb (aka Charles Sherwood Stratton), a young boy whose restricted growth gave him the appearance of a perfectly proportioned miniature man. Tom Thumb was launched in London in 1844, and he captivated all who saw himâincluding the Queen and members of the royal family when, in what was one of his biggest coups, Barnum took him to Buckingham Palace. The Queen's enchantment was such that they were invited to return, and as a regular visitor Barnum invested in a court suit for Tom. But not everyone approved. There was a disturbing undertow to the presence at Buckingham Palace of a court dwarf, and even the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, was concerned. Thomas Hood was ârevolted by the royal running after the American mite', and Dickens, in a satirical reply, declared that the royal patronage of the diminutive star was a threat to the constitution. He joked that the Queen was so taken with Tom that, âsoon in the two little porticoes at the Horse Guards, two Tom Thumbs will be daily seen, doing duty mounted on a pair of Shetland ponies.'

The serious underlying message was the stigma of philistinism in the Queen. Her enthusiasm for Tom Thumb and various popular entertainments was at odds with the increasing concern of the middle-class core of her subjects that pleasure should be allied to learning. Of course, at Madame Tussaud's the agenda was never in doubt. Marie's loyal public subscribed pretty much wholeheartedly to her professed educational aims. The

Pictorial Times

in 1844 wrote, âMadame Tussaud's great merit and strongest claim consist in the fact that, aware of the influence which exhibitions exercise upon the public taste, her arrangements have always been made with a view to refine the mind, extend the knowledge and exalt the sentiments of her visitors.' Her pedagogical packaging was so artful that it successfully disguised the contents. With her usual foresight, Marie ensured that Tom Thumb took up his place in her exhibition, so that she too could

make money from the public fixation with the quick-witted little boy with the huge talent for impersonation and amusing patter.

Tom Thumb unintentionally caused one of the biggest culture shocks of the century. The historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon was actually unhinged by the constant crowds for Tom Thumb compared to the cavernous emptiness of his own exhibition in the next-door room at the Egyptian Hall. On 21 April 1846, he took out an advertisement in

The Times

. Headed âThe exquisite feeling of the English people for high art', it noted that âGeneral Tom Thumb last week received 12,000 people who paid him £600; B. R. Haydon who has devoted 42 years to elevate their taste was honoured by the visits of 133 and a half (child) producing just £513 and 6.' In private he poured his pain into his diary: âThey push, they scream, they faint, they cry help and murder and oh and ah! They see my bills and my boards and don't read them. Their eyes are open, their sense is shut. It is an insanity, a rabies, a madness, a furore, a dream.' Shortly afterwards he cut his throat and shot himself.

This tragedy exposed a dichotomy that was becoming more pronounced and a matter of public debateâa growing conflict between commercial culture and its more orthodox forms. Could instruction and amusement be mixed? Were crowds compatible with culture? Were the barbarians getting too close to the gate? The debate touched Marie and all those who were part of a growing phalanx of entertainers making fortunes from middle-class taste. They trod a precarious path between being taken seriously for their educational aims and being dismissed as tacky money-grubbers.

You could not be in London long before realizing the popularity of Madame Tussaud, and Barnum clearly recognized a fellow genius for publicity. His facility for hype and spin matched hers. He similarly played the press, and always dressed up his entertainments for maximum appeal to an increasingly discriminating middle-class market. His exhibition was not a museum but âa Cyclopaedical Synopsis of everything worth seeing and knowing'. A club of uncertain provenance became the weapon that killed Captain Cook, and so on. In his autobiography Barnum refers only

en passant

to his failed attempt to buy Madame Tussaud's, but the Tussaud family history corroborates his interest. In 1890 Barnum sat for Joseph Theodore Tussaud, a great-grandson of

Marie's. Apparently, at this sitting Barnum related how, many years before, he had tried to induce his grandfather to transport Madame Tussaud's exhibition to New York, but the negotiations had fallen through at the last minute. One imagines that Marie, after all her experiences with Philipstal and with her husband, would have been immensely resistant to relinquishing her life's work to a fast-talking, fast-thinking American showman whose flash-trash philosophy was so very different from her own more refined style.

Marie and her family's success in distinguishing their own attraction was all the more remarkable given the competition they faced from a burgeoning sector of commercial entertainments catering to middle-class consumers in search self-improvement. London boasted an impressive array of purpose-built pleasure resorts, and at this time one can see cranking into being the prototypes of the amusement park and the tourist attraction. At the Colosseum a novelty was London's

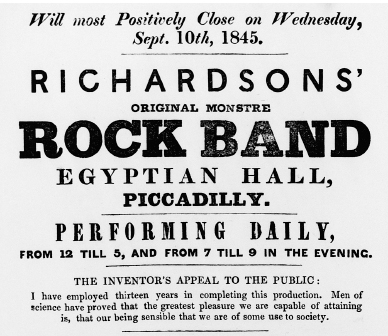

first ever passenger lift, or âascending room', described as a âsmall covered room which will contain from 10â20 persons and may be raised by secret machinery with its company to the first gallery'. If this was the height of sophistication at the Polytechnic Institution, which took a theme park approach to science, a ride in a diving bell offered a new depth of learning. But the Egyptian Hall remained unbeatable for sheer variety under one roof. Featuring in one programme were a group of Obijawa Indians, who enjoyed immense success, and Richardson's Rock Band, âthe instruments of which are cut from solid rock'. The rock group comprised the mason, who had spent thirteen years making the instruments, and his three sons. The Egyptian Hall took pride in presentation, and created special effects with great panache. A contemporary sets the scene: âThe astonished visitor is transported in an instant from the crowded streets of the metropolis to the centre of a tropical forest in which are seen as in real life all its various inhabitants from the huge elephant and rhino to the most diminutive quadruped.' Of course, lest there be any suspicion that this is just fun, he continues, âJuvenile minds will be taught a lesson beyond calculation valuable; they will behold in the great volume of creation, the works of an all-wise providence and the lesson will be indelibly impressed on their minds.'

Another element in the appeal of these pleasure domes was social. Although Marie had pioneered the promenade concert, others were beginning to cotton on to the concept. Dickens described a gala night at the Colosseum which could have been choreographed by Marie: âThe band was stationed in the Egyptian tent; the hall of mirrors superbly ornamented and illuminated served for the principal promenade.' His account of the paying guests is almost pure Jane Austen: âMatchmaking mammas in abundanceâsleepy papas in proportionâunmarried daughters in scoresâmarriageable men in rather smaller numbersâgreedy dowagers in the refreshment roomâflirting daughters in the corners and envious old maids everywhere.'

Madame Tussaud was not always the subject of positive publicity. The advent of two new illustrated periodicals in the early 1840s, the

Illustrated London News

and

Punch

, extended her publicity network. But whereas the former tended to be positive towards her exhibitionâit once likened her wax doubles to getting a personal introduction to

the famousâthe latter was relentlessly critical, and throughout the final decade of her life she was a constant target for amusing jibes.

A persistent erroneous belief is that

Punch

coined the name of the Chamber of Horrors. In fact the name was generated in-house, and was first used in advertisements in the

Illustrated London News

in July 1843. The price of admission to âNapoleon and the Chamber of Horrors' was listed as sixpence.

Punch

took up the name much later, in 1846, when it mentioned it in an article on a newly launched tableau. It had taken offence at a poster advertising âa magnificent display of court dresses of surpassing richness, comprising 25 ladies and gentlemen's costumes intended to convey to the MIDDLE CLASSES an idea of the ROYAL SPLENDOUR, a most splendid novelty and calculated to display to young persons much necessary instruction'. Given the economic slump that was affecting much of the country, with a large proportion of the population suffering real hardship,

Punch

felt this new exhibition was jarring. Such superficial pretensions were especially inappropriate given the great influence of the exhibition, and a misguided application of the educational function in which the Tussauds took such prideâit was this that formed the thrust of

Punch

's objection. Under the heading âGreat moral lesson at Madame Tussaud's' it launched its tirade. âKnow all men, that Madame Tussaud has come out as a great public teacher. She has converted her exhibition in Baker Street into an educational institution, and has resolved herself and her sons into a Society for the Diffusion of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge.' It then quoted verbatim her advertisement, before going on, âIf we were in the place of Madame Tussaud we would superadd to our collection some twice twenty-five of more shabby old working dresses, of surpassing uncouthness, intended to amuse and instruct the superior classes by giving them an idea of laborious indigence.'

The article's last paragraph was the one that fixed the Chamber of Horrors in the national phrase book. The phrase had been used without irony by the Tussauds, but here the context was entirely sarcastic:

The collection should include specimens of the Irish peasantry, the hand loom weavers, and other starving portions of the population all in their characteristic tatters; and also inmates of the various work-houses in the ignominious garb presented for them by the Poor Law.

But this department of the exhibition should be contained in a separate Chamber of Horrors and half a guinea entrance fee should be charged for the benefit of living originals.

Over the years, allusions to Madame Tussaudâsome mean, some affectionateâpeppered the pages of

Punch

. The constant references were as much as anything a sign of the exhibition's status in public life, for by the mid-1840s it was regularly being referred to in the press as âthe leading exhibition of the metropolis'. Today at Baker Street Underground station there is a pre-recorded announcement: âAlight here for Madame Tussauds'âthe only commercial attraction so honoured. But even in Dickens's time its status as a landmark was firmly established: