Jungle of Snakes (14 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

Meanwhile, the paratroopers in Algiers enjoyed their newfound adulation among the city’s young female

pieds-noirs

. Their officers found satisfaction in a dirty job well done and looked forward to some cleaner, real soldiering out in the

hinterland against main-force insurgent units. In the words of Colonel Bigeard, counterinsurgency operations in Algiers had

been a battle of “blood and shit.”

11

The Battle on the Frontiers

FRENCH DECREES ISSUED IN THE spring of 1956 divided Algeria into three zones: a zone of operation, a pacification zone, and

a forbidden zone. The allocation of counterinsurgency forces logically followed this division. The zone of operations was

the killing ground where elite mobile French forces relentlessly pursued guerrilla bands with the objective of eliminating

them. In the pacification zones, which embraced the most populous and fertile areas, French conscript and reserve formations

tried to protect the civilian population, European and Muslim alike, from terrorist attacks. Here security was accompanied

by major economic reforms, education, and propaganda indoctrination. French strategists designated sparsely populated areas

that were adjacent to the pacification zones as forbidden zones (

zones interdites

). The strategic intent was to separate the rebels from their sources of supplies and recruits while providing security for

the pacification zones. They were beyond the pale, a region from where the population was evacuated and relocated in settlement

camps controlled by the army. Thereafter, the army was permitted to fire on anyone seen moving in the forbidden zones.

Having established the parameters by which it would operate, the French military went to work. It employed overwhelming force

to drive the FLN’s military organization, the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), out of Algeria. Most ALN fighters took

refuge in the neighboring countries of Morocco and Tunisia. Those who continued the fight inside Algeria became dependent

on external supply sources. The French recognized this vulnerability and concentrated on isolating Algeria. Nourished by good

intelligence, the French navy intercepted ships carrying arms to Algeria. They also blocked aerial resupply of the guerrillas.

Outside of Algeria, French secret agents waged a successful intimidation campaign, including targeted assassinations, against

international arms dealers. Because of these measures, the insurgents remained starved for effective firearms and munitions.

Inside Algeria, the French organized

harki

units of “loyal” Algerians. A farsighted settler, Jean Servier, had overcome official resistance to organize light companies

from FLN defectors. Servier insisted that these

harki

units serve near their homes so they could protect their own families from FLN retaliation. Armed with shotguns, intimately

familiar with the local environment, Servier’s

harkis

soon demonstrated their worth by eliminating local insurgents. News about the opportunity for regular employment spread rapidly

and French-loyal village elders began organizing their own

harki

units. They were essentially miniature tribal armies. Over a two-year period beginning in 1957, the number of these lightly

armed native forces serving as village militia rose to involve some 60,000 Algerians. When associated with skilled French

SAS leaders the

harkis

proved to be very effective in denying the insurgents access to rural people.

However, the Algerian borders were open to infiltration from guerrilla sanctuaries in Morocco and Tunisia. The recent memory

of Indochina, where Communist guerrillas enjoyed free passage across international borders, persuaded the French to tackle

this challenge decisively. The French utilized a classic counterinsurgency approach that the Romans who constructed Hadrian’s

Wall would have admired. The French built extensive fortified barriers along 500 miles of the Moroccan border in the west.

But it was in the east along the Tunisian border where they erected a state-of-the-art defensive barrier. This was the famous

Morice Line, named after the French defense minister, a 200-mile-long line extending from the sea to the Sahara desert. An

eight-foot-high electrified wire barrier carrying 5,000 volts ran through the middle of a wide minefield overlooked by regularly

spaced watchtowers. When the guerrillas tried to break through the fence, detection devices triggered an alarm system. Of

critical importance, the Morice Line, like Hadrian’s Wall, was not simply a passive defense system. Rather, both worked in

association with mobile combat formations who met insurgent breakthroughs wherever they occurred. Precalibrated artillery

fire rained down wherever automatic devices detected a breach, while mobile combat patrols rushed along a purpose built highway

that ran along most of the Algerian side of the barrier to deal with the penetration. If a breach occurred in the roadless,

remote southern sector, heli copters flew the reaction force to the scene of the incident. The entire system involved 80,000

soldiers, watching and waiting for any FLN attempt to reinforce their beleaguered fighters in Algeria.

The challenge came soon. Raiders probed the Morice Line looking for weaknesses. They employed high-tension wire cutters purchased

in Germany, insulated ramps, tunnels, and blasting charges. After opening a breach the raiders tried to hold the nearby terrain

to permit the passage of reinforcements and supplies before the French resealed the border. Nothing worked. Infiltration parties

attempting to outflank the line at its southern end found themselves exposed to French air power in the open Sahara and were

slaughtered. So the armed wing of the FLN, the ALN regulars, tried a series of escalating conventional attacks against the

Morice Line.

A large ALN force fought through the Morice Line in May 1958 only to encounter the reconnaissance group of the First Foreign

Legion Parachute Regiment. Colonel Pierre Jeanpierre, one of Massu’s paratroop leaders during the Battle of Algiers, died

while leading his Legionnaires in a decisive counterattack that resealed the line. In another climactic action, waves of ALN

fighters managed to breach the Morice Line only to be pinned down by the French mechanized and helicopter-delivered reaction

forces. A total of 620 of the 820 men who penetrated the line were killed or captured. The series of efforts to breach the

French fortified barriers cost the ALN upward of 6,000 men, a devastating setback that compelled the FLN to cease trying to

breach the French fortifications.

While the French navy prevented the guerrillas from smuggling arms and men into Algeria, the Morice Line and the Moroccan

barrier effectively blocked infiltration by land and thereby “established a kind of closed hunting preserve” where the French

security forces could relentlessly conduct a battle of attrition.

1

Only some 8,000 ALN fighters remained inside Algeria. With the veterans gone, most of the remnants were young, inexperienced

recruits who predictably suffered heavily whenever drawn into combat with the French.

Because the ALN dispersed and went into hiding, increasing numbers of Algerian civilians withdrew support for the rebels.

In June 1960 an FLN political leader reported to his government in exile, “It becomes increasingly impossible to penetrate

the barriers in order to nurture the revolution in the interior . . . unless directed, supplied with fresh troops, effective

weaponry, and money in great amounts, the underground forces will not be able to live for a long time let alone achieve victory

. . . The organic infrastructure has been dismantled in the urban centers, and it is increasingly nonexistent in the countryside.”

2

The Return of Charles de Gaulle

Just when it appeared that the FLN was on the verge of defeat the entire political climate in France changed. In Algeria,

the

pieds-noirs

had greeted various proposals for reform as betrayal. On April 26, 1958, some 8,000 Europeans marched through Algiers and

made a public oath: “Against whatever odds, on our tombs and on our cradles, taking our dead on the field of honor as our

witnesses, we swear to live and die as Frenchmen in the land of Algiers, forever French.”

3

In France, press investigations of abuses in the resettlement program and new revelations about the practice of torture demoralized

the public. The war’s unpopularity combined with numerous economic and social gripes to reduce domestic support for the French

government. A cabinet crisis fractured the weakened government and presented an opportunity for right-wing activists to strike.

On the day a new cabinet was scheduled to present its program to the National Assembly,

pied-noir

activist groups in Algiers began widespread demonstrations in an effort to influence the vote. They feared that the new French

government would abandon them and denounced the government for plotting “a diplomatic Dien Bien Phu.” By the evening of May

13, 1958, they controlled Algiers and had established an emergency government. The French army in Algeria realized that it

held enormous political clout and supported this new government. France teetered on the edge of revolution.

Into the ensuing leadership void stepped Charles de Gaulle. The settlers’ revolt found the sixty-seven-year-old war hero in

rural retirement working on his war memoirs. But he had been closely following political developments and was far from displeased

when a new opportunity presented itself. In a memorable speech on May 19, 1958, de Gaulle deployed his brilliant rhetoric

to reassure the nation. Alluding to events in Algeria, de Gaulle said that France confronted “an extremely grave national

crisis.” But he also told the nation that it could “prove to be the beginning of a kind of resurrection.”

4

The National Assembly voted de Gaulle full powers for six months, thereby ending the Fourth Republic. De Gaulle, in turn,

judged Algeria a “millstone round France’s neck.”

5

In his view the era of European colonialism was coming to an end and there was no longer any alternative for Algeria except

self-determination. But it was of crucial importance that France grant Algeria this right. It could not be forced upon any

self-respecting French government at the point of a gun or the detonation a terrorist bomb. As the new leader phrased it,

prior to negotiations the insurgents had to check “the knives in the cloakroom.”

6

De Gaulle knew that to arrive at an acceptable solution he had to appeal to diverse political constituents and consequently

had to handle the situation with extreme circumspection. Thus, he moved slowly and cautiously, and with calculated vagueness.

By so doing he failed to capitalize on the opportunity created by military success in Algeria.

FLN leaders would later say that the weeks following de Gaulle’s rise to power marked a low ebb for their cause. Their military

forces had hurled themselves against the Morice Line and been badly defeated. Their troops were demoralized and when de Gaulle

spoke about true equality for all Algerians within the French republic the great mass of Algerians appeared receptive to compromise.

FLN leaders knew that they had to do something before de Gaulle’s government could consolidate power. They responded brilliantly

with a diplomatic offensive designed to take advantage of Cold War rivalry between the East and West by proclaiming a revolutionary

Provisional Government of the Republic of Algeria. Arab nations hastened to recognize the new government. The Communist bloc,

except for the USSR, followed. FLN spokesmen hinted at a new flexibility regarding a negotiated settlement and the international

press enthusiastically endorsed this notion. Yet even as they won an important victory on the international front, military

events in Algeria again threatened to defeat the FLN.

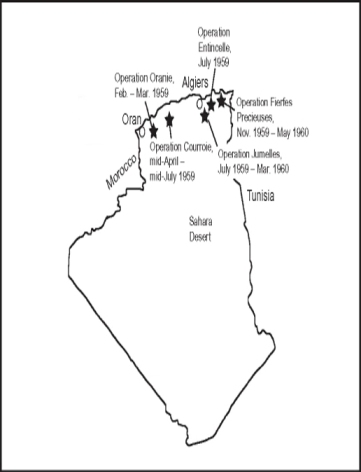

The Challe Plan

When de Gaulle assumed power he began to replace the command team in Algeria with his own loyalists. He chose General Maurice

Challe to command the military. It proved an inspired choice. Still vigorous at age fifty-three, Challe had served with distinction

in the Resistance during World War II. He had provided the British with valuable intelligence on the eve of the Normandy Invasion

and earned both a British medal and a personal citation from Winston Churchill. Although trained as an airman, Challe possessed

a keen appreciation for land tactics. Unlike his predecessor, he did not dabble in politics but rather was an open and honest

leader with a surpassing ability to forge an interservice, team approach to problem solving. De Gaulle ordered Challe to deliver

a crushing blow to the already reeling insurgent cause by a series of offensives designed to reduce the rebel pockets one

after another. In de Gaulle’s mind this offensive was like a preassault strategic bombardment designed to create a receptive

environment for what ever he decided to do next.

Challe, in turn, believed that too many French soldiers, about 380,000 by his count, had been assigned passive roles guarding

the Morice Line, securing the country’s infrastructure, and protecting its villages. Only 15,000 remained in the General Reserve

to conduct active operations. The result was that the French military had designated vast swaths of Algeria as “no-go zones,”

which effectively ceded these areas to the FLN. Indeed, the French had ruefully labeled one such zone the “FLN republic.”

Unwilling to remain passive and reactive, Challe planned to concentrate overwhelming force against each traditional insurgent

stronghold. After eliminating the rebels and inserting pacification teams to take control of the population and prevent the

insurgents from re-forming, Challe intended to move against another stronghold. He introduced his strategy to the army in

Algeria with a simple catch phrase that everyone could understand: “Neither the

djebel

[hill] nor the night must be left to the FLN.” He made sure that he had the right sort of tactical commanders to realize his

vision by sacking nearly half the sector commanders and replacing them with more aggressive colonels.