Jungle of Snakes (11 page)

Authors: James R. Arnold

In Algeria, when the Europeans recovered from their initial shock and assessed the situation, they quickly perceived the rebels’

weaknesses. Among the

pieds-noirs

a deep sense of outrage replaced initial fears. The FLN campaign slogan calling on the Europeans to leave or risk death, “The

suitcase or the coffin,” amazed them. For generations they had made this country their home and it was inconceivable that

anyone should challenge their right to call themselves Algerians.

In France itself, the All Saints’ Day revolt presented a major political challenge. There were two alternatives to war: rapid

and fair integration of Algeria into metropolitan France and disengagement. Neither choice was politically acceptable. Ethnic,

religious, cultural, and racial divisions between French and Algerians made equitable integration a nonstarter. Disengagement

was psychologically difficult. French leaders, the army, and the people still reeled from the humiliating events of 1940,

when a German blitzkrieg overran the fatherland. Postwar loss of the colonial empire threatened to reduce France to second-rate

status. The gallant but futile defense of Dien Bien Phu was still very much in everyone’s mind. France’s Algerian lobby and

the army were powerful political influences and neither body could countenance losing another valuable and prestige-conferring

colony. The politicians bent with the prevailing wind.

French determination to hold Algeria arose from the interplay of multiple factors, the most salient of which were the presence

of close to a million settlers, the legal fiction that Algeria was an integral part of France, wounded pride, and last but

not least the discovery of oil in the Sahara desert in Algeria’s far south.

For these reasons the mandate to retain Algeria as part of metropolitan France extended across political parties. The French

premier representing the Radical Party, Pierre Mendès-France, told the National Assembly in November 1954 that Algeria was

part of France and that it was inconceivable that it should be otherwise. He emphasized that a “blow struck at the French

of Algeria, be they Moslem or European, is a blow struck at the whole nation.” Applause from delegates of all stripes greeted

his words as he emotionally intoned there could be no compromise when it came to “defending the internal peace of the nation

and the integrity of the Republic.”

3

Mendès-France pledged to send massive military reinforcements to restore order. His minister of the interior, François Mitterrand,

a member of the left wing, added that “the only possible negotiation is war.”

4

Later, Mendès-France’s successor, the Socialist premier Guy Mollet, said, “France without Algeria would be no longer France.”

5

This viewpoint and its undergirding logic dictated how France responded to the crisis. For the duration of the conflict the

French government treated the insurgents as citizens engaged in outlaw behavior. They were subject to the law in the same

way a citizen of Paris or Marseilles was subject to the law. The government sent the military to Algeria to restore and maintain

order in the same way it dispatched riot police to a city on the mainland. This legal distinction that described Algeria as

part of metropolitan France carried significant implications. In the arena of foreign affairs, no international law prevented

a government from suppressing an internal rebellion. No foreign power could legitimately support the rebels or intervene on

their behalf. In the arena of French military conduct, counterinsurgency efforts were nominally subject to French law. This

would be observed in the breach, with the government itself permitting and encouraging extralegal measures with a wink and

a nod.

The French Military

From a military standpoint, the outbreak of terror in Algeria came at a bad time. The army’s most experienced guerrilla fighters

were still in slow transit from Indochina. Troubles in neighboring Morocco and Tunisia, both of which were also asserting

their right to self-rule, tied down another 140,000 men. Commitment to NATO occupied additional divisions. Few trained reserves

remained. In Algeria itself, there were about 49,000 security forces of all types among whom a mere 3,500 were combat effective

soldiers. The available air transport was indicative of the military’s poor state of combat readiness: eight leftover World

War II–era Junkers transport planes, a type already obsolete ten years earlier, and one helicopter. Given that the insurgents’

tactic of choice was terror, the role of the police would be crucial. Yet the total number of police in Algeria barely exceeded

the size of the Parisian police force. The logical answer to the manpower shortage was to recall French reserves, but such

strong medicine was politically unpalatable.

Instead, French authorities brazenly dismissed the initial wave of terrorist acts as “ordinary banditry.” This failure to

appreciate the true challenge enabled the rebels to pass through the revolution’s precarious first stage. Henceforth, its

spread became inevitable. By the time French authorities recognized the rebellion for what it was, there was no easy recourse.

Firm, even bold political and military action was the only possible strategy for victory. Instead, the succession of weak

French governments tried hastily devised reforms to undercut the insurgents. These economic and social reforms only hardened

the insurgents’ resolve and encouraged the FLN to limit the alternatives they presented to the French colonists to two: “the

suitcase or the coffin.”

IN ALGERIA THE initial official response to the outbreak of violence was the predictable overreaction of an embarrassed administration.

First came heavy-handed, indiscriminate arrests of suspects, thereby converting neutrals to the cause of the insurgency. Next

came French government resistance to reform, a stance widely acclaimed by hard-liners in France and the

pieds-noirs

. And then, too late, came official proposals for meaningful reform.

During the winter of 1954–55, the French army conducted several clumsy operations featuring conventional, large-scale pincer

operations designed to trap and eliminate the guerrillas. The insurgents were seldom to be found. Somehow their intelligence

network—the Arab “bush telegraph,” using beacon fires lit from peak to peak—outpaced both the French mechanized columns and

their foot-slogging brethren. It was soon apparent that in the battle for intelligence the insurgents held a big edge. Worse,

the large scale sweeps proved counterproductive. One French analyst caustically observed, “To send in tank units, to destroy

villages, to bombard certain zones, this is no longer the fine comb [

ratissage

]; it is using a sledgehammer to kill fleas. And what is much more serious, it is to encourage the young—and sometimes the

less young—to go into the maquis.”

6

Indeed, an FLN leader confirmed that this style of French operations was “our best recruiting agent.”

7

After one typical French military operation caused the death of an innocent Muslim woman, an FLN leader remarked, “

Voilà

, we’ve won another battle. They hate the French a little more now. The stupid bastards are winning the war for us.”

8

At this time French leaders still failed to understand thoroughly the po-liti cal dimensions of the struggle. FLN appeals

to nationalism were useful insurgent tools in the competition for popular support inside Algeria. More effective was the endless

repetition of a potent propaganda message delivered to Algerian Muslims who sat on the fence: “The French swore they would

never leave Indochina; they left. Now they pledge to never abandon Algeria.” In 1956, after France announced the in dependence

of neighboring Morocco and Tunisia, revolutionary propagandists had two examples much closer to home of France reneging on

its solemn vows.

Jacques Soustelle, soon to be appointed governor-general to Algeria, described the essential question asked by all French

sympathizers: “ ‘Are you leaving or staying?’ There is no officer, who assuming command of his post in a village . . . has

not been asked this question by the local notables. What it meant was: ‘If the village raises the French flag, if this or

that family head agrees to become mayor, if we send our sons and daughters to school, if we hand out weapons of self-defense,

if we refuse to supply the fellaghas roaming around the djebel with barley, sheep and money, will you, the army, be here to

defend us from reprisals?’”

9

If armed French regulars possessed too much firepower for the insurgents to risk an attack and European civilians were not

yet on the target list, French sympathizers among the Muslim population remained vulnerable. A village policeman found with

his throat slit—a particularly humiliating death normally reserved for slaughtering sheep and goats—and an FLN placard pinned

to his corpse, an Algerian vineyard manager employed by a French owner found tortured and killed, and an outspoken pro-French

village elder subjected to slow death within a few hundred yards of a French army base, all conveyed the terrorist message

to cease collaborating with the French.

Targeted terrorism also sought to drive a wedge between the Muslim and the French population by compelling rural Muslims to

burn schools and destroy public properties in order to bring French repression. The FLN also worked to raise Muslim political

consciousness by rigid enforcement of Islamic rites. One notable tactic was to enforce a ban on public tobacco consumption.

A few public chastisements where a smoker’s nose was cut off went a long way toward enforcing a national tobacco boycott.

The Front also organized local political cadres whose main job was to collect taxes to support the insurgency. Having initially

made the strategic error of impatience, the FLN focused on building revolutionary infrastructure by mobilizing the population

through persuasion and terror.

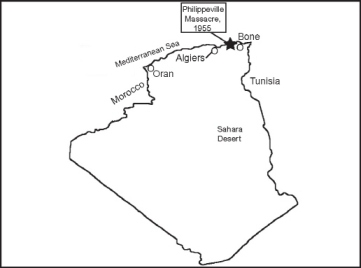

The Philippeville Massacre

THE STRATEGY PROMOTED BY FRENCH president Mendès-France called for simultaneous reform and military pressure. When the insurrection

began there were 2,000 employees in the general government of Algeria. Eight were Muslims. To help redress this imbalance

a new school of administration gave Muslim Algerians access to public sector management positions. Nationwide, only 15 percent

of Muslim children attended school. Proposed educational measures addressed this issue. The average European’s salary was

twenty-eight times that of the Muslim. Economic measures sought to reduce the gap between Algerian and European salaries.

In sum, comprehensive economic and social reforms would give Algeria more equal standing within France’s political structure.

The problem with this approach was obvious: it threatened the

pieds-noirs

, who wanted to preserve the status quo, but failed to satisfy the FLN, which wanted nothing less than full in dependence.

Lack of progress in Algeria and fierce opposition from the Algerian lobby brought down the Mendès-France government in February

1955. The Algerian lobby in France and many

pieds-noirs

celebrated the government’s collapse. In their view, now could begin the proper employment of force. FLN leaders likewise

welcomed Mendès-France’s ouster. They regarded his promise of liberal reform as a dire political threat to their goal of total

in dependence.

One of Mendès-France’s last acts before his ouster was to appoint a new governor-general for Algeria, Jacques Soustelle. Soustelle

was a remarkable man who by age forty-three had already enjoyed an outstanding career as academic, political thinker, administrator,

and World War II partisan. In February 1955 Soustelle toured Algeria and quickly saw that the situation was much worse than

metropolitan France realized. The French military had understood the paramount importance of recruiting and employing large

numbers of Muslims. In turn, the guerrillas made examples of these “loyal” Muslims, subjecting them to torture, mutilation,

and death. Soustelle realized that FLN terror had driven the Muslim majority into fearful neutrality. “The Administration

and the Army,” Soustelle wrote, “had seen information dry up . . . Fear closed mouths and hardened faces.”

1

Soustelle represented the school of thought that poverty breeds revolution. His response, the so-called Soustelle Plan, and

its subsequent variants sought to combat the insurrection through social and economic reforms. This school of analysis had

superficial validity. The impoverished peasants of the Aurès mountains had little to lose by joining the insurrection. However,

the urban poor were equally destitute yet did not initially participate in the insurrection. A grand strategy based on the

wrong diagnosis could not succeed. Expensive social and economic reforms designed to conquer poverty were of limited value

when the conflict was really about politics. The FLN did not fight to banish poverty; they fought to banish French rule.

The arrival of substantial French reinforcements in Algeria frustrated the insurgents’ hopes for a quick victory. French military

pressure drove many guerrilla bands into hiding, where the hard winter of 1954–55 seriously depleted their ranks. In March

1955 Soustelle asked the government for the right to adapt legislation to war time conditions. At month’s end the National

Assembly, while refusing to use the word

war

, voted for a state of emergency that strengthened the powers of the army. But these powers applied only to a limited zone

of the Aurès. The National Assembly also authorized the first population regroupments in order to move “contaminated” populations

to “settlement camps.”

2

During this time the insurgents continued to have trouble obtaining arms and ammunition—probably only half of the guerrillas

who had participated in the All Saints’ Day attacks were armed—so they could not openly challenge French security forces.

FLN leaders realized that there would be no war-winning Algerian version of Dien Bien Phu. Henceforth, insurgent strategy

relied upon fighting a low-level war of attrition that pitted their scarce armed manpower and ammunition against French national

will.

Yet they had to be seen to remain active in order to prevent the Muslim population from rallying to the French cause and to

encourage foreign support. So the FLN lifted restrictions on attacks against European civilians and embarked on a terror campaign

without limits. Civilians became targets for indiscriminate bombings and shootings. The goal was to provoke repressive French

military responses in order to alienate both the Algerian and the French people. A hand grenade tossed into a crowded cafe

or a homemade bomb detonated on a school bus carrying French children could be expected to bring furious reprisals against

the local Muslim population. The new policy came into sharp focus on August 20, 1955, in and around the harbor city of Philippeville.

The man who had the covert assignment of identifying and eliminating the FLN in Philippeville was Paul Aussaresses. He was

a Special services intelligence officer and a veteran of clandestine operations in World War II and Indochina—in other words,

an experienced, discreet officer perfectly at ease with following orders and keeping his mouth shut. He had killed men and

had participated in interrogations but up to this time never tortured anyone. That was about to change.

The Philippeville police, whose ranks composed exclusively

pieds-noirs

and “assimilated” Muslims, told him that the terrorists were up to something but that no one knew precisely what. They matter-of-factly

stated that the only way to extract information from unobliging prisoners was torture. They asserted that torture was legitimate

to obtain information that would save lives. Specifically, if they arrested a suspect who was involved in preparing a terrorist

act such as setting a time bomb in a French grade school, a forced confession could foil the plot. Their logic persuaded Aussaresses

and men like him: it was better to torture a suspected terrorist, to make a single person suffer, than to allow scores of

innocent people be killed and maimed.

Aussaresses patiently assembled a list of FLN members and sympathizers. Many were common criminals, which made his job easier.

When they refused to talk the police took charge. Often a beating was enough. For particularly stubborn suspects the police

used a field radio as a power source and attached electrodes to the ears and testicles, the infamous

gégène

. Regardless of outcome, when the interrogation was over Aussaresses ordered the prisoners executed. He justified summary

executions on the basis that the regular justice system was suitable for a peacetime situation in metropolitan France but

this was Algeria, where a war of terror was under way.

In spite of Aussaresses’ efforts, FLN guerrillas goaded the civilian population in and around Philippeville into indiscriminate

acts of violence. Some of the worst atrocities came in the mining town of El-Halia, where Muslim workers who had seemed to

enjoy a rare degree of equality with the French mine managers brutally turned on the small European community. The village

constables were conveniently absent, so the attack came as a complete surprise. Guided by mineworkers, guerrillas first isolated

the village by cutting telegraph lines and disabling the emergency radio transmitter. Then attackers went house to house,

slaughtering Europe ans without regard to age or sex. The terrorist mob entered homes and used billhooks and pitchforks to

commit acts of unspeakable savagery, including ripping open the bellies of nursing mothers and hurling their infants against

the wall until their brains spilled out. Thirty-seven settlers including ten children under fifteen years of age perished.

Elsewhere, purportedly urged on by chants from mobs of Muslim women and muezzins’ broadcasts from the minarets exhorting the

attackers to slaughter Europeans in the cause of “holy war,” similar scenes of savagery played out. The victims of August

20, 1955, included seventy-one Eu rope ans and fifty Algerians killed and scores of others maimed. What was particularly notable

about the butchery was the careful planning that took place involving so many Muslims whom the French community regarded as

friendly. The sense of betrayal coupled with the many sites of blood-soaked horror produced a brutal French retaliation.

When paratroopers belonging to a crack French regiment arrived in Philippeville, they beheld the mob continuing the slaughter.

Under such circumstances the paratroopers had little interest in separating the insurgents from the civilians, a difficult

task under any circumstance. They fired on whoever ran. Later, they rounded up prisoners, lined them up against the wall,

and opened fire with machine guns. There were so many killed that burial teams used bulldozers to inter the corpses. French

sources acknowledged killing 1,273 “insurgents.” The actual figure is unknowable.

What is certain is that the Philippeville Massacre, as it became known, had profound consequences for the war. The rebel atrocities

implacably hardened the hearts of the

pieds-noirs

and forever altered the behavior of many members of the French army and security forces. But it was the retaliation that mattered

most. It handed the insurgents a victory and provided confirmation going forward for their strategy of indiscriminate terror.

All the terrorists needed to do was to create an incident and await the predictable French overreaction. The greatest threat

to the FLN strategic goal of full independence had been French political reform such as the measures proposed by Governor

Soustelle that led to Muslim integration into a French political entity. The French reprisal at Philippeville caused moderate

Muslims to repudiate integration. Guerrilla recruitment soared.

When he first heard the news, Soustelle flew to the scene of the massacre. The savagery inflicted on French women and children,

the suffering of the mutilated in the hospitals—fingers hacked off, throats half slit as a warning—sickened Soustelle. From

this time on his ideal of liberal reform became a remote priority, superseded by his determination to crush the rebellion.

Nonetheless, Soustelle was wise enough to understand that the massacre was a victory for the FLN because it created an abyss

separating the European and Muslim communities “through which flowed a river of blood.”

3

ON THE INTERNATIONAL front, the Philippeville Massacre caused the United Nations to address the Algerian problem for the first

time. This was an important political victory for the FLN. The insurgents received material and propaganda support from the

Communist bloc, from Iraq and Egypt, and most importantly from neighboring Morocco and Tunisia. At the United Nations it was

easy for France’s enemies to portray Algerian terrorists as nationalists striving to depose their colonial oppressors. An

examination of a graph showing FLN activity since the start of the insurgency revealed regular peaks in November-December

for the years 1955 to 1957. French intelligence called these peaks “United Nations fever” since they corresponded to the time

the UN General Assembly met to discuss the situation in Algeria.

In France, the Philippeville Massacre also led to a new Socialist government in January 1956, headed by Premier Guy Mollet.

Mollet’s policy toward Algeria was first to win the war and then to implement reforms. Mollet and like-minded French politicians

understood the vital importance of national will in murky counterinsurgency warfare. He acceded to the army’s request for

reinforcements by taking the important step of calling up a large number of reservists and extending the term of service for

conscripts by 50 percent, from nineteen to twenty-seven months. These measures effectively nationalized the war by putting

more citizens, instead of exclusively the military professionals, in harm’s way. By so doing, Mollet hoped to engage the French

people, to make it really matter to them who won in Algeria. He explained his calculation to a French newspaper in April 1956:

“The action for Algeria will be effective only with the confident support of the entire nation, with its total commitment.”

4

Mollet also appointed Robert Lacoste, a popular veteran of both world wars, to replace Soustelle as governor-general. The

strength of the army in Algeria swelled from around 50,000 in 1954 to more than half a million men by 1958, the largest overseas

military commitment in French history. Mollet’s emphasis on military action before political action notably shackled Lacoste.

Nonetheless, Lacoste raised the Algerian minimum wage, pushed land redistribution for Algeria’s land-hungry peasants, improved

education, and decreed that half of all vacancies in public service go to Muslims.

Had these measures been implemented a decade earlier they might have changed history. Instead, coming in the wake of the Philippeville

Massacre, most Muslims saw them as a tardy response to FLN pressure. By the summer of 1956 the rebels had won over a majority

of previously uncommitted political leaders. These were the men France had depended on to help them win the battle for the

hearts and minds of the Muslim masses. Then in October 1956 came an electrifying French intelligence coup.