Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (27 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

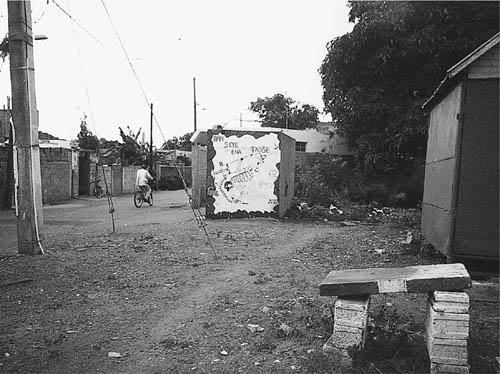

Figure 9.1 “Try It and You’re Stuck” (Mauritian Kreol proverb), Baie du Tombeau, Mauritius, 2002. Photo by author.

Many instead used both rounds of compensation and the sale of land and houses to pay off substantial debts. Unscrupulous brokers (Chagossians, among them, according to some) enabled many of the real estate sales, which are widely seen as having significantly undervalued the properties. Some real estate brokers preyed upon islanders desperate for cash, buying at low prices and quickly flipping the properties. Others offered the

new homeowners loans, forcing them to put their property up as collateral and then charging high rates of interest; when they were unable to repay the loans, the lenders seized the property.

After leaving school for his job in a cologne factory, Alex eventually found work as a stevedore at the docks in Port Louis’s main harbor. “But then the docks fired him,” Rita said, and “he had no work.” Before long, she recounted, “he wasn’t working . . .

sagren

. . . he drank.” In 1990, at the age of 38, Alex died, having ruined his body with alcohol and drugs, leaving behind a wife and five boys under the age of 15.

“The same as with Eddy,” Rita said of one of her other sons. One day he “told me he was going out, that he was going to look for work. He went two days and he didn’t come back—I was very worried and went looking all over for him. It was then that his friends from the streets drove him into drugs.”

Eddy grew addicted to heroin and soon “he became like a bone,” Rita said. He was a “skeleton. His insides were completely finished.”

When Eddy died, Rita had to take a Rs7,000 loan to pay for the burial. Like other Chagossians she went to a local “

madam kredi

”—a moneylender who took Rita’s government-issued pension card, withdrawing her monthly pension to collect the Rs7,000 and interest.

When Rénault died at 11 for reasons still mysterious to the family after selling water and begging for money at the cemetery, Rita buried him in the clothes he wore for his First Communion. “The same clothes, I got them out. The same clothes, I put on him,” she said.

“I have suffered so much, David, here in Mauritius. I am telling you look at how many—three sons, one daughter, and my husband. Five people have died in my arms. It’s not easy. . . . Not easy. It’s not easy, David.”

*

I note the qualification in passing to point out that the ancestors of all humans come from Africa.

DYING OF

SAGREN

“

Sagren

, that’s to say, it’s

sagren

for his country. Where he came from, he didn’t experience

mizer

like we were experiencing here. He was seeing it in his eyes,

laba

.

*

His children were going without, were going without food. They didn’t have anything,” Rita said of Julien’s death. “And so he got so, so many worries, do you understand? That’s

sagren

. Many people have died like that. You know, David?”

“Died from—” I started to ask, wanting to understand more about how people could die from

sagren

.

“

Sagren

! Yes! When one has

sagren

in your heart, it eats at you. No doctor, no one will be able to heal you! If you have a

sagren

, if you, even—you can’t get it out. That’s to say, David—

Ayo

! What can you do? Let it go—something that came on like that. There are many people that can’t bear it.”

“Mmm,” I uttered, trying to take in what she was saying.

“Yes. Do you understand? Then, it goes, it goes, until at the end, you don’t want to eat, you don’t want anything. Nothing. You don’t want it. . . . There’s nothing that you do, that you have that’s good. You’ve withdrawn from the world completely and entered into a state of

sagren

.”

“Have you experienced

sagren

?” I asked.

“Yes.

Sagren

. Yes,” Rita replied slowly.

“It’s very hard,” I said.

“Do you understand? You have

sagren

when in your country you haven’t experienced things like this. Here you’re finding food in the trashcan.”

How do we understand Julien’s dying of

sagren

, of profound sorrow? How do we understand the deaths of others that Chagossians likewise attribute

to

sagren

? And how do we understand the islanders’ comparisons of an almost disease-free, healthy life in Chagos to one filled with sickness and death in Mauritius and the Seychelles? And how are we to make sense of the comparisons people make between an idyllic life in Chagos and what Rita and others call the “hell” of exile?

To start, we must return to neighborhoods like Cassis and Pointe aux Sables where Chagossians have lived since the time when Rita and Julien arrived in Mauritius. Rita now lives in the

Cité Ilois

, the Ilois Plot, in Pointe aux Sables, where she received her small concrete block house and some land from the compensation provided in the 1980s. Her yard there is hedged in by a wall nailed together out of corrugated iron and wood. Three dogs patrol the inside, chained to a line allowing them to roam back and forth, barking at passersby. On one side of the house stand several trees: three mango, a bred murum, and two coconut—only one produces nuts. On the other side, Rita has allowed her youngest son Ivo to build a smaller three-room metal-sheeted home for his wife and two sons; they couldn’t afford to buy a place of their own. Hanging on the wall inside her house, Rita proudly displays a sun-bleached poster of a fruit and vegetable still life—pineapple, broccoli, melons, grapes, green-hued oranges. Another print of a dew-spotted rose hangs nearby, alongside a poster of a coconut tree on a beach in the Seychelles. Rita told me it reminds her of beaches in Peros.

Housing conditions have improved to some extent for those like Rita who received and kept their compensation homes. For most who didn’t get a home or had to sell theirs, however, conditions remain poor. A 1997 WHO-funded report described how housing varies “between the decent”—that is, compensation housing—“and the flimsy”—homes like those occupied since the earliest days in exile, usually built with a metal roof and walls of metal sheeting or perhaps some combination of wood and concrete block, with kitchen and sanitary facilities located outside the home and generally lacking running water and electricity.

1

Even with the improvements some enjoyed when they obtained a concrete-block house, most still live in conditions that are among the worst in Mauritius and the Seychelles. Overcrowding remains a serious problem. Most are still concentrated in the poorest, least desirable, most disadvantaged, and most unhealthy neighborhoods. Many live with dangerous structural deficiencies and limited access to basic services: 40 percent are without indoor plumbing and more than one-quarter lack running water.

2

Generally housing problems are more critical for those in Mauritius than for those in the Seychelles, in line with wider national differences. In Mauritius,

the islanders’ housing conditions are broadly comparable to those found in the poor townships of South Africa.

Compounding their housing difficulties, most Chagossians still struggle to find work. At the time of my 2002–3 survey, just over a third (38.8 percent) of the able-bodied first generation and less than two-thirds (60.6 percent) of the second generation were working.

3

In many households, only a single adult had a job. Other households relied on multiple income earners, from teens working in factories to elderly women doing laundry for neighbors, to support a family.

4

Median monthly income was less than $2 a day: far below the median incomes for their Mauritian and Seychellois neighbors.

5

Of those who are employed, many still have jobs at the bottom of the Mauritian pay scale, characterized by high job insecurity, temporary duration, and informal employment commitments. Chagossians are still primarily employed in manual labor: as dockers and stevedores in the shipping industry; as janitorial, domestic, and child care workers; as informal construction workers and bricklayers; as factory workers. Some find various piecework employment, often to supplement other jobs, including stitching shoes, assembling decorative furnishings, and weaving brooms from coconut palms.

In general, those born in Mauritius and the Seychelles or who left Chagos at a very young age seem to have been more successful in securing employment and better remunerated jobs than their elders. These groups have little if any memory of Chagos and experienced less disruption in their lives as a result of the expulsion (although I stress that this is a relative distinction). And in contrast to most of the first generation, which received little if any formal education in Mauritius or the Seychelles, this group has had at least some chance to benefit from the Mauritian and Seychellois education systems (however discriminatory they are).

In part because the group in the Seychelles is composed disproportionately of islanders who arrived in the first years of their lives, islanders in the Seychelles are, economically speaking, generally better off than their counterparts in Mauritius. While some are living in the most impoverished conditions in the Seychelles, significant numbers enjoy secure public sector employment as bureaucrats, teachers, and police officers. By contrast, the rare few that have government jobs or similarly stable employment in Mauritius are notable for having escaped the impoverishment facing the vast majority there.

The different economic outcomes in the two nations is a complicated matter that can only be understood with extensive comparative study. Some of the difference is surely attributable to higher standards of living enjoyed in the Seychelles (per capita GDP is roughly $7,500 higher), a better and

more equitable education system, and lower levels of discrimination. At the same time, just as the relative economic success of some World War II–era Japanese-American internees has done little to negate their experiences of internment, any (relative) material comfort that

some

may have found in the Seychelles in no way negates other ways in which they have suffered and continue to face pain and discrimination.

Among many in both countries, in fact, there remains deep pessimism about their economic and employment prospects. The French aphorism, “Ceux qui sont riches seront toujours riches, ceux qui sont pauvres restent toujours pauvres”—the rich will always be rich; the poor will always be poor—is a kind of chorus in Mauritius among some young adult Chagossians.

I asked Jacques Victor, who was then working weekends as an informal clothing vendor, if he thought it would be possible to find a better paying job. “In Mauritius, no. In Mauritius, no,” Mr. Victor responded in English—one of a very few islanders to speak at least some of the official national language, which is generally a marker of middle-or upper-class status. “Ilois have the qualifications,” he explained, but Mauritian employers say, “‘How can they have this kind of qualification?’ They much prefer [us] lower than low. It’s like that.”

As we ended our conversation, I asked Mr. Victor if there was anything else he wanted to tell me. “I want to return to our land. Be there now—get our lives that we were living, yesterday,” he said. “Maybe my children will get jobs.”

SAGREN

AS SYNECDOCHE

“It gave me such suffering, David, and to this day, I still have this suffering. In my heart, it’s not at all gone. Not at all gone,” Rita told me from her house in Pointe aux Sables. “Look at how many of my children have died. How can I explain it to you? If we were

laba

, Alex would be here, Eddy would be here, Rénault would be here. . . . Eddy died from drugs but

laba

, we didn’t have them.”

Rita continued, “They pulled us from there to come take us to hell. Drugs are ravaging people. The children aren’t working, they’re following friends to the side of having, to the side of having problems, understand? It’s always the same, it’s not easy.”

“It’s a very sad story,” was all I could muster in response.

“There, in St. George’s cemetery, I have three boys—three boys, two girls,” she said. To the deaths of her own four children, Rita added the death of Alex’s wife, who committed suicide in 2001, dousing herself with gasoline and setting herself afire. Their five boys—five of Rita’s grandchildren—were left orphaned.

We return now to the deaths of Julien and others from

sagren

and the comparison of a disease-free, healthy life in Chagos to one of illness, drugs, and death in exile. Examining first the contrast between lives of health and lives of illness, we see that the islanders’ diagnosis is an accurate one: The contrast they describe represents an accurate portrayal of changing health conditions before and after the expulsion. While Chagossian health was once better than that in Mauritius, it is now comparable to the low levels of health characterizing the poorest sectors of Mauritian society, a nation with one of the highest incidences of chronic disease in the world.

6