Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (12 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

Stu’s Strategic Island Concept offered an answer, The Navy, for its part, was “buoyed by the fact that there were so many such islands in the Indian Ocean.” Most of the islands were controlled by the British, and the Navy “did not see any real difficulty in persuading Great Britain to enter into . . . an agreement” to create island bases.

18

As with the Pacific Lake strategy after World War II, government officials ultimately hoped to ensure U.S. dominance in another ocean by controlling every available piece of territory, or at least by denying their use to the Soviet Union and China.

Stu’s work on the Strategic Island Concept reflects the recognition by the late 1950s that the power of the United States had diminished relative to that of its Cold War opponents. The shift was probably less significant in real terms than it was in its perception, but this made little difference at the time to U.S. officials and others in the world. At the same time, domestic political concerns about appearing “weak” on “defense” or giving ground to the communists were probably as significant as perceptions of growing U.S. weakness in shaping foreign and military policy.

Indeed, most U.S. officials understood that the United States remained the most powerful nation on Earth. By the time President Kennedy took

office, both the President and Secretary of Defense McNamara knew that fears about a “missile gap” with the Soviet Union were unfounded, that the Soviet Union and China no longer represented a unified threat, and that the United States enjoyed “overwhelming strategic dominance.” In quantitative terms, Gareth Porter shows that although U.S. military strength narrowed from forty times greater than the Soviet Union in 1954 to nine times greater in 1965, the difference still represented the greatest disparity between a major power and its nearest rival since the seventeenth century.

19

Aware of this power imbalance, that the United States possessed a dominance so great that in effect no other nation could constrain most of its contemplated activities, officials across successive presidential administrations exploited a “new freedom of action” to pursue “more aggressive and interventionist policies.”

20

SELECTING DIEGO GARCIA

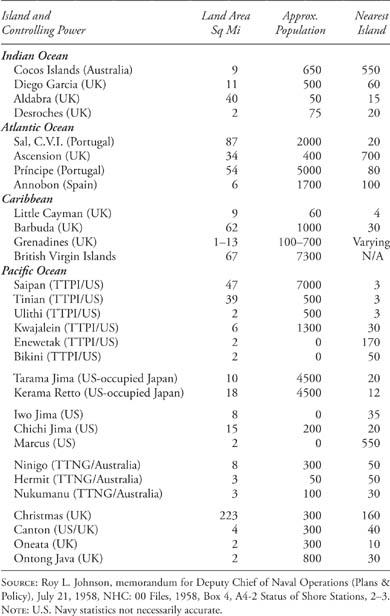

Although Stu and the Long Range Objectives Group researched scores of islands (see

table 3.1

), they increasingly focused their attention on Diego Garcia. While looking for islands, the Navy considered not just an island’s strategic location but certain political, economic, cultural, and social factors. As Stu explained, island selection was based on a weighing of “military and political factors”: “Our military criteria were location, airfield potential, anchorage potential,” he wrote. “Our political criteria were minimal population, isolation, present [administrative] status, historical and ethnic factors.”

21

After a survey of Diego Garcia, Stu and Op-93 determined that Diego Garcia was ideal: On “military” grounds, Diego Garcia was close to perfect, as Stu had recognized. Among the “political” criteria, the Navy found that Chagos had a small population and was “among the most neglected minor backwaters of the world.”

22

Importantly, Navy officials understood that the archipelago was not only of marginal interest globally but also of marginal interest to Mauritius: Given Chagos’s limited economic output, Britain would have an easy time convincing Mauritian leaders to give up the islands. People of Indian descent dominated Mauritius, and officials understood that the Indo-Mauritian leadership would probably care little about uprooting an isolated, mostly African population whose ties to Mauritius were historically tenuous. Given the general isolation and obscurity of Chagos and its people, the Navy realized that few elsewhere would notice, let alone object.

T

ABLE

3.1

“Strategic Island Concept”: Information on Potential Sites

THE BIKINIANS

The Navy’s search for strategically located islands with small easy-to-remove non-Western populations was not without precedent. After World War II, the U.S. Navy was given the responsibility for orchestrating postwar nuclear weapons tests and first needed to find an isolated island test site. “We just took out dozens of maps and started looking for remote sites,” explained Horacio Rivero, one of two officers responsible for finding a location. “After checking the Atlantic, we moved to the West Coast and just kept looking.”

23

Rivero knew a lot about islands. He was born in Ponce, Puerto Rico in 1910. During World War II he served on the USS

San Juan

in battles for islands across the Pacific, including those at Kwajalein, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Guadalcanal, the Gilbert Islands, the Santa Cruz Islands, the Solomon Islands, and Rabaul. After the war, Commander Rivero worked at the Los Alamos nuclear weapons lab under William S. Parsons; “Deak,” as he was known, was a crew member on the Enola Gay, helping to arm the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

24

In his next posting, Rivero and colleague Frederick L. Ashworth considered more than a dozen nuclear test sites around the world’s oceans. Officials ruled out most because the waters surrounding the islands were too shallow, the populations too large, or the weather undependable. Rivero and Ashworth considered the Caroline Islands in Micronesia, Bikar and Taongi in the Marshall Islands, and even the Galapagos (the Interior Department had the foresight to strike Darwin’s famed islands from the list because of their rare species).

25

Initially the Navy was most interested in one of the Carolines, as one memorandum explained, “partly because evacuation of natives would not be a major problem.” Eventually Rivero and Ashworth selected the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The Navy was particularly pleased that Bikini had an indigenous population of only about 170.

26

The Navy sent a commodore—“Battling Ben” Wyatt—to “ask” the Bikinians for use of their islands. However, the outcome was a foregone conclusion: President Harry Truman had already approved the removal, and preparations for the test had begun on the islands.

27

For their part, the Bikinians were “awed” by the U.S. defeat of Japan and grateful for the help the United States had provided since the war. They “believe[d] that they were powerless to resist the wishes of the United States.”

28

On March 7, 1946, less than one month after posing its “question,” the Navy completed the removal of the Bikinians to the Rongerik Atoll,

elsewhere in the Marshall Islands. Within months it became clear that the move to Rongerik had been “ill-conceived and poorly planned,” leaving the Bikinians in dire conditions. The

New York Times

wrote in classically ethnocentric language that the Bikinians “will probably be repatriated if they insist on it, though the United States military authorities say they can’t see why they should want to: Bikini and Rongerik look as alike as two Idaho potatoes.”

29

By 1948, the Bikinians were running out of food and suffering from malnutrition. After planning to move them to Ujelang, the Navy sent them to a temporary camp on Kwajalein Island, near a major U.S. base. Later that year, the Navy moved the islanders to a new permanent home on Kili Island. By 1952, the government was forced to make an emergency food drop on Kili as conditions again deteriorated for the people. In 1956, the United States paid the Bikinians $25,000 (in $1 bills) and created a $3 million trust fund making annual payments of about $15 per person. “The Bikinians were completely self-sufficient before 1946,” explains attorney Jonathan Weisgall, “but after years of exile they virtually lost the will to provide for themselves.”

30

Between 1946 and 1958, the Navy conducted 68 atomic and hydrogen bomb tests in Bikini,

31

removing an additional 147 people from Enewetak Atoll and all the people of Lib Island. On March 1, 1954, the first U.S. hydrogen bomb test spread a cloud of radiation over 7,500 square miles of ocean, leaving Bikini Island “hopelessly contaminated” and covering the inhabitants of the Rongelap and Utirik atolls.

32

In addition to deaths and disease from this and other radiation, the removals and the disruption to Marshallese societies led to declining social, cultural, physical, and economic conditions, high rates of suicide, infant health deficits, and slum housing conditions, to name just a few of their debilitating effects.

33

One of the two officers responsible for selecting Bikini, Horacio Rivero, was rewarded for his work by being made an admiral. Appropriately sharing a first name with both the figure from bootstraps mythology (Alger) and the naval hero from the Battle of Trafalgar (Nelson), Rivero became the first Latino admiral in U.S. Navy history. (That Rivero married Hazel Hooper, of Horacio, Kansas, seems beyond coincidence, underlining the significance of Rivero’s name.) Rivero’s next promotion was to become the third director of the Long Range Objectives Group, where he discovered another search for islands and Stu Barber’s “brilliant idea” for Diego Garcia.

34

BASE DISPLACEMENT

That Horacio Rivero would come to play a role in the displacement of both the Bikinians and the Chagossians is hardly a coincidence. Around the world, often in isolated locations, often on islands, and often affecting indigenous populations, the U.S. military has displaced local peoples as part of the creation of military facilities. Almost always, these removals have led to the impoverishment of those affected. And among the services, Rivero’s Navy has frequently been involved. In total there are at least sixteen documented cases of base displacement outside the continental United States. Some of these took place prior to World War II. Other displacements initially began during World War II combat under the pretext of wartime necessity; most of the people removed in wartime, however, were prevented from returning at war’s end, with the early displacements only paving the way for the displacement of even greater numbers in peacetime. The sixteen cases followed more than a century during which the United States engaged in the systematic displacement of native peoples in North America.

35

In Hawai‘i, the United States first took possession of Pearl Harbor in 1887 when officials coerced the indigenous monarchy into granting exclusive access to the protected bay.

36

Half a century later, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Navy seized Koho‘olawe, the smallest of the eight major islands, and ordered its inhabitants to leave. The service turned the island, which is “home to some of the most sacred historical places in Hawai‘ian culture,” including 544 archaeological sites, into a weapons testing range.

37

In 2000, the Navy finally returned the environmentally devastated island to the state of Hawai‘i.

In 1899, a year after the United States seized Guam from Spain, the U.S. Navy designated the entire island a U.S. naval station. The Navy administered the island until Japan captured it three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the United States retook Guam in 1944, the military acquired more than 45 percent of its available land. Today, the military controls around one-third of the island and has plans for a major expansion of the base’s capacity to host more than 20,000 troops shifted from bases in Japan, South Korea, and Europe.

38

In Panama, the United States carried out nineteen distinct land expropriations around the Panama Canal Zone between 1908 and 1931. Some were for fourteen bases established in the country and some were for the canal.

39

In the Philippines, Clark Air Base and other U.S. bases were built on land previously reserved for the indigenous Aetas people. According to McCaffrey, “they ended up combing military trash to survive.”

40

In Alaska, in 1942, the Navy displaced Aleutian islanders from their homelands to live in abandoned canneries and mines in southern Alaska for three years. The military also seized Attu Island for a Coast Guard station; it was eventually designated a wilderness area in 1980. In 1988, an act of Congress delivered some compensation to the surviving islanders.

41

In the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, the Navy carried out repeated removals on the small island of Vieques. Between 1941 and 1943, and again in 1947, the U.S. Navy displaced thousands of people from their lands, seizing three-quarters of Vieques for military use. In 1961, the Navy announced plans to seize the entire island and evict all 8,000 inhabitants before Governor Luis Muñoz Martin convinced President Kennedy to halt the expropriations in light of UN and Eastern bloc scrutiny of the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. Few benefits followed military occupation. Stagnation, poverty, unemployment, prostitution, violence, and the disruption of subsistence and other productive activities became the rule.

42