Iran: Empire of the Mind (28 page)

Adel Shah’s brother Ebrahim had initially controlled Isfahan, but after he moved east Karim Khan Zand and Ali Mardan Khan Bakhtiari took over the western provinces, coming to an agreement with each other and ruling in the name of another Safavid prince, Esma‘il III. Step by step Karim Khan removed his rivals, killing Ali Mardan Khan in 1754 and deposing Esma‘il in 1759. He stabilised his regime by fighting off external rivals also: Azad Khan, another of Nader Shah’s Afghan commanders, who controlled Azerbaijan; and Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar, who had his power base in Mazanderan. Karim Khan also fought the Ottomans and conquered Basra; something Nader Shah had never achieved.

The rule of Karim Khan Zand was an island of relative calm and peace in an otherwise bloody and destructive period. In the years of the Afghan revolt and the reign of Nader Shah, many cities in Iran were devastated by war and repression (some, like Kerman, more than once—in 1719 and 1747—and it was to suffer terribly again in 1794). By mid-century most of the built-up area of Isfahan, the former capital, was deserted; inhabited only by owls and wild animals. In the last years of the Safavids, it had been a thriving city of 550,000 people,

16

one of the largest cities in the world; a similar size to London at the time, or bigger. By the end of the siege of 1722 only 100,000 people were left, and although many citizens returned thereafter the number fell yet further during the Afghan occupation and later so that by 1736 there were only 50,000 left.

17

It has been estimated

that the overall total population of Persia fell from around nine million at the beginning of the century to perhaps six million or less by mid-century through war, disease and emigration; and that population levels did not begin to rise significantly again until after 1800,

18

(by contrast, the population of England rose from around six million in 1700 to around nine million in 1800). Trade fell to one-fifth of its previous level.

19

But despite the pitiful state into which the country had fallen, the major outside powers, Russia and the Ottoman Empire, did not intervene as they had in 1722-1725. It was partly that they were busy elsewhere, but surely also that the outcome of their previous attempts had not encouraged them to repeat the experiment.

The eighteenth century has been portrayed as a period of tribal resurgence

20

, and the names of the main parties contending for supremacy for much of the century—Afshar, Zand and Qajar—alone point in that direction. Many of the troops fighting in the civil wars, most of them horsemen, were recruited from the nomadic tribes, who still would have comprised between a third and a half of the population. The make-up of the tribes was complex and far from static—there were many different terms to express different kinds of clans, tribal subdivisions, tribes and tribal confederations; and the alliances between tribes formed, broke and reformed in new combinations from time to time. At the best of times, as for centuries if not millennia, the tribes lived in an uneasy tension with the more settled people of the towns and villages. The tribes and the settled peoples were usually divided by ethnicity, language or religion, or by a combination of them. The tribesmen lived in more rugged mountain and arid territory, and had more rugged attitudes to go with their more marginal existence. They raised livestock, and traded their surplus to supply the towns and villages with wool and meat. In return they received goods they could not make for themselves; some foodstuffs, but also weapons. But as well as this more open form of exchange, there was often an exchange on the basis of security, more or less disguised. Peasants might pay tribute to a local tribal leader to have their crops left alone at harvest time, or to avoid raiding that might otherwise mean some being carried off as slaves (especially in the north-east). Or the local tribal leader might

often have been co-opted, in a more formalised arrangement, to serve as the regional governor, collecting tax instead of protection money. But in general, before, during and after this period, the tribes and their leaders tended to have the upper hand, and to exploit it politically. Their position of supremacy was only decisively overturned when the twentieth century was quite well advanced.

Karim Khan Zand did not have Nader’s insatiable love of war and lust for conquest. His governmental system was less highly geared. After he removed Esma‘il, Karim Khan refused to make himself Shah, ruling instead as

vakil-e ra’aya

(deputy or regent of the people): a modern-sounding choice of title that probably reflects his awareness of the weariness of the Iranian people and their longing for peace. He restored traditional Shi‘ism as the religion in his territories, dropping Nader’s experiment with Sunnism. Karim Khan chose Shiraz as his capital, and built mosques, elegant gardens and palaces there that still stand, erasing the scars of the revolt of 1744 and beautifying the city that had been the home of Sa’di and Hafez. Karim Khan ruled there until his death in 1779. He was a ruthless, tough leader, as was necessary in those harsh times; but he also acquired an enduring reputation for modesty, compassion, pragmatism and good government, unlike most of his rivals. His reputation shone the brighter for the surrounding ugliness and violence of his times.

Renewed War

After Karim Khan’s death in 1779, Persia lapsed again into the misery of civil war. This time the struggle was between various Zand princes on the one side and the Qajars, based in Mazanderan, on the other. The Qajars were united by Agha Mohammad Khan (the son of Mohammad Hasan Khan Qajar) who had fallen into the hands of Adel Shah in 1747 or 1748 and had been castrated at Adel Shah’s orders when he was only five or six years old. After that he was kept as a hostage by Karim Khan, but treated kindly.

21

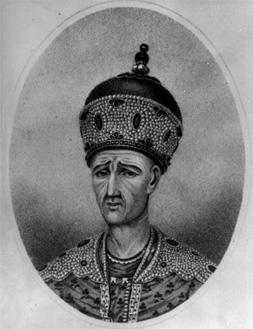

He grew up to be a fiercely intelligent, pragmatic man, but grim and bitter, with a bad temper and a vicious cruel streak that grew worse as he got older. He was never able to overcome the loss of his manhood, and

was depicted looking drawn and beardless in contemporary illustrations as a sign of it.

When Karim Khan died Agha Mohammad escaped to the north, where he successfully conciliated other branches of the Qajar tribe that had previously feuded with his family, but had to fight his own brothers to establish his dominance (Agha Mohammad’s rise was much more firmly based on his lineage and on the Qajar tribe than that of Nader Shah was based on the Afshars). That achieved, and with the help of the Yomut Turkmen allies that had long supported his family, he ejected Zand forces from Mazanderan and began campaigning south of the Alborz mountains. But when he arrived outside Tehran, the gates were closed against him. The citizens politely told him that the Zands were in charge in Isfahan and that meant the people of Tehran must obey the Zands (with the implication that if Agha Mohammad Khan could take Isfahan, they would obey him too). Agha Mohammad marched on to Isfahan, taking it in the early part of 1785. He was then duly accepted into Tehran in March 1786, after other successful campaigning in the west. From that point it became clear that he intended to establish himself as ruler of the whole country, and Tehran has been the capital since that time.

There was to be much more fighting before Agha Mohammad could rule supreme, and he was still far from secure in the south. Isfahan changed hands several times, but the Zands could not deliver a knock-out blow either, and in January 1789 their leader (Ja‘far Khan) was assassinated. The ruling family of the Zands then fought among themselves for the leadership, until Lotf Ali Khan Zand, a young grand-nephew of Karim Khan, entered Shiraz in May 1789, establishing his control.

Lotf Ali Khan was young and charismatic, and was a natural focus for the hopes of those who remembered the the prestige of his great-uncle, but militarily he was at a disadvantage from the start. He fought off an attack by Agha Mohammad in June 1789 but when he made a move on Isfahan in 1791 Shiraz revolted against him behind his back. He returned but was unable to get back into his former capital and was forced to lay siege to the city. The Shirazis sent for help to Agha Mohammad, and sent Lotf Ali Khan’s family as prisoners to him too. Lotf Ali Khan was able

to defeat a combined force of Qajars and troops from Shiraz, but the city still held out and in 1792 Agha Mohammad himself marched south with a large army. Agha Mohammad by this time was showing some of the fierce anger and vicious cruelty for which he later became notorious. At one point he saw a coin minted in Lotf Ali’s name and became so enraged that he gave orders for the Zand’s son to be castrated.

Lotf Ali Khan now nearly brought off a coup that could have won him the war. As Agha Mohammad approached Shiraz, he camped with his Qajar troops near the ancient sites of Persepolis and Istakhr. After night fell, Lotf Ali approached the camp with a smaller force and attacked from several directions in the dark. Chaos erupted, and Agha Mohammad was in great danger when Lotf Ali sent thirty or forty men right into the camp, who penetrated as far as Agha Mohammad’s private compound, which was defended against them by a few musketeers. At this point one of Agha Mohammad’s courtiers went to Lotf Ali and told him that Agha Mohammad had fled. The battle appeared to be over and Lotf ‘li was persuaded that further fighting would only risk his own troops killing each other in the dark. He ordered his men to sheathe their sabres. Many of them dispersed, plundered the parts of the camp they were in control of and left the scene with the booty. But when dawn came Lotf Ali discovered to his horror that Agha Mohammad was still there. He had not fled, and the Qajar troops were regrouping around him. Lotf Ali Khan was surrounded and outnumbered by the Qajar forces, and only had 1,000 of his own men still with him. He quickly withdrew, and fled eastwards

22

.

From this point on Lotf Ali Khan’s support began to dwindle away. He captured Kerman, but Agha Mohammad Khan moved against the city and besieged it. The Qajars broke into the city by treachery in October 1794 and Lotf Ali Khan fled to Bam. Agha Mohammad ordered that the women and children of Kerman should be given over to his soldiers as slaves, and those of the men that were not killed he had blinded. To be sure that his orders were carried out the eyeballs were cut out, brought to him in baskets and poured out on the floor—20,000 of them. Sir John Malcolm recorded that these blinded victims were later to be found begging across Persia, telling the story of the disaster that had befallen their city.

23

Lotf Ali Khan was betrayed in Bam, and taken in chains to Agha Mohammad, who ordered his Turkmen slaves to do to him ‘what had been done by the people of Lot’. After the gang-rape, Lotf Ali Khan was blinded and sent to Tehran, where he was tortured to death.

24

Fig. 9. Agha Mohammad Shah ended the civil wars of the eighteenth century and established the Qajar dynasty on a firm footing, but left behind a reputation for extreme cruelty.

Agha Mohammad Khan was now the undisputed master of the Iranian plateau. He turned to the north-west, where he marched into Georgia, reasserting Persian sovereignty there and (in September 1795) conquering Tbilisi after a furious battle in which the Georgians seemed to be winning at several points, despite their inferior numbers. In Tbilisi thousands were massacred, and 15,000 women and children were taken away as slaves. But the King of Georgia had put himself under Russian protection in 1783. The destruction of Tbilisi caused anger in St Petersburg, and was later to bring humiliation for Persia in the Caucasus.

In the spring of 1796 (1210

AH

) Agha Mohammad had himself crowned on the Moghan plain, where Nader Shah had assumed the same dignity exactly sixty years earlier. At the coronation he wore armbands on which were mounted the

Darya-ye Nur

and the

Taj-e Mah

, jewels taken from Lotf Ali Khan (they had previously belonged to Nader Shah). Agha Mohammad Khan liked jewels. After the coronation he marched east to Khorasan, where he accepted the submission of Shahrokh, Nader Shah’s grandson. He had Shahrokh tortured until he gave up more jewels, also

from the treasure Nader had brought away from Delhi. Shahrokh died of the treatment shortly afterwards, in Damghan.

Agha Mohammad Shah had now resumed control of the main territories of Safavid Persia, with the exception of the Afghan provinces. But he did not enjoy them, or his jewels, for long. In June 1797, while campaigning in what is now Nagorno-Karabakh, he was stabbed to death by two of his servants, whom he had sentenced to be executed but unwisely left alive and at liberty overnight.

Religious Change: Seeds of Revolution