Iran: Empire of the Mind (24 page)

After the death of Abbas the Great in 1629 the Safavid dynasty endured for almost a century, but except for an interlude in the reign of Shah Abbas II (1642-66) it was a period of stagnation. Baghdad was lost to the Ottomans again in 1638 and the Treaty of Zohab in 1639 fixed the Ottoman/Persian boundary in its present-day position between Iran and Iraq. Abbas II took Kandahar from the Moghuls in 1648 but thereafter there was peace in the east also.

Militarily, the Safavid State probably reached its apogee under Shah Abbas the Great and Abbas II. But there is good reason to judge that, despite its classification with Ottoman Turkey and Moghul India as one of the Gunpowder Empires (by Marshall G. Hodgson), the practices and structures of the Safavid Empire were transformed to a lesser extent by the introduction of gunpowder weapons than those other empires were. Cannon and muskets were present in Persian armies, but as an add-on to previous patterns of warfare rather than transforming the conduct of war as happened elsewhere. The mounted tradition of Persian lance-and bow warfare, harking back culturally to Ferdowsi, was resistant to the introduction of awkward and noisy firearms. Their cavalry usually outclassed that of their enemies, but Persians did not take to heavy cannon and the greater technical demands of siege warfare as the Ottomans and Moghuls did. The great distances, lack of navigable rivers, rugged terrain and poor roads of the Iranian plateau did not favour the transport of heavy cannon. Most Iranian cities were either unwalled or were protected by crumbling walls centuries old—at a time when huge, sophisticated and highly expensive fortifications were being constructed in Europe and elsewhere to deal with the challenge of heavy cannon. Persia’s Military Revolution was left incomplete.

20

Alcohol seems to have played a significant part in the poor showing of the later Safavid monarchs. From the time of Shah Esma‘il and before, drinking sessions had been a part of the group rituals of the Qezelbash, building probably on the ancient practices of the Mongols and the Turkic tribes in Central Asia, but also on ghuluww Sufi practice and the Persian tradition of razm o bazm. There is a story that Esmail drank wine in a boat on the Tigris while watching the execution of his defeated enemies after he conquered Baghdad in 1508,

21

but as we have seen his drinking accelerated after his defeat at the battle of Chaldiran, and some accounts suggest that alcohol was instrumental in his early death in 1524. Within the wider Islamic culture that was hostile to alcohol, it seems that in court circles wine had all the added allure of the forbidden (one could draw a crude parallel with the way in which binge drinking is a feature of British and other traditionally Protestant societies whose religious authorities tended in the past to frown on alcohol consumption). Shah Tahmasp appears to have stopped drinking in 1532/33 and maintained his pledge until his death in 1576, but alcohol was blamed by contemporaries as a cause or a contributory factor in the deaths of his successor Shah Esma‘il II, Shah Safi(reigned 1629-1642) and Shah Abbas II (1642-1666).

22

Some of this can perhaps be attributed to a moralising judgement on rulers who were thought to have failed more generally; for writers who disapproved of alcohol, wine-drinking was a sufficient explanation for (or at least a sign of) incompetence, indolence, or general moral weakness and bad character (Shah Abbas I drank too, without damaging his reputation). But there is too much evidence for the drinking to be dismissed as the invention of chroniclers. The reign of Shah Soleiman represents the apotheosis of the phenomenon.

Soleiman came to the throne in 1666 and reigned for the next 28 years. A contemporary reported –

He was tall, strong and active, a little too effeminate for a monarch—with a Roman nose, very well proportioned to other parts, very large blue eyes and a middling mouth, a beard dyed black, shaved round and well turned back, even to his ears. His manner was affable but nevertheless majestic. He had a masculine and agreeable voice, a gentle way of speaking and was so very engaging that, when you had bowed to him he seemed in some measure to return it by a courteous inclination of his head, and this he always did smiling.

23

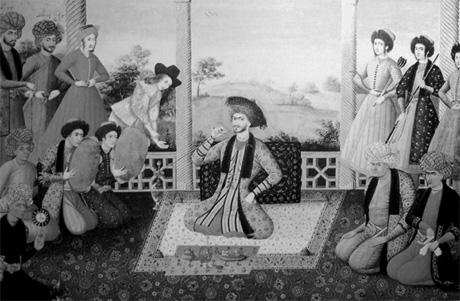

Fig. 7. Shah Soleiman, attended by musicians, eunuchs, other courtiers and a rather ungainly European supplicant. The Safavid government machine continued to function, but drifted into neglect over the period of his reign and that of his son.

Soleiman’s reign was for the most part quiet (with the exception, at the beginning, of the out-of-the-blue incursion into Mazanderan of the robber king Stenka Razin and his Don Cossacks in 1668-69). Some fine mosques and palaces were built, but one could take those as material symbols of the growing diversion of economic resources into religious endowments, and of the blinkered, inward-looking tendency of the monarch and his court; both of which were to prove damaging in the long run. Soleiman showed little interest in governing, and left state business to his officials. Sometimes he would amuse himself by forcing them (especially the most pious ones) to drink to the dregs a specially huge goblet of wine (called the

hazar pishah

). Sometimes they collapsed and had to be carried out. If they stayed on their feet, the Shah might, for a joke, order them to explain their views of important matters of government.

24

Shah Soleiman himself drank heavily, despite occasional outbreaks of temperance induced by health worries and religious conscience.

25

His pleasure-loving insouciance was the natural outcome of his upbringing in the harem. He had little sense of the world beyond the court and little interest in it. He merely wanted to continue the lazy life he had enjoyed before, augmented by the luxuries he had formerly been denied. But some contemporary accounts say that when drunk he could turn nasty; that on one occasion he had his brother blinded, and that at other times he ordered executions.

It is a testament to the strength and sophistication of the Safavid state and its bureaucracy that it continued to function despite the lack of a strong monarch. In other Islamic states this situation often permitted the emergence of a vizier or chief minister as the effective ruler; it seems that in Isfahan the influence of other important office-holders (and that of Maryam Begum, the Shah’s aunt, who came to dominate the harem) was enough to prevent any single personality achieving dominance. But as time went on the officials acted more and more in their own private and factional interests, and against the interests of their rivals; less and less in the interest of the state. Bureaucracies are not of themselves virtuous institutions—they need firm masters and periodic reform to reinforce an ethic of service if they are not to go wrong; and if they see their masters acting irresponsibly, the officials imitate their vices.

The influence of the politically-inclined ulema at court strengthened as the Shah’s involvement in business slumped, and one leading cleric, Mohammad Baqer Majlesi, has been associated with a deliberate policy of targeting minorities for persecution (at least in the case of Hindu Indian merchants) to appeal to the worst instincts among the people and thereby enhance the popularity of the regime.

26

Persecution was episodic and unpredictable, sometimes concentrating on the Indians or Jews, sometimes on the Armenians, sometimes on the Sufis, or the Zoroastrians or Sunni Muslims in the provinces. But in general, despite the protection the Jews and Christians at least should have enjoyed as People of the Book, the minorities were disadvantaged at law, subject to everyday humiliations, and vulnerable to the ambitions of

akhund

(rabble-rousing preachers) who

might seek greater fame for themselves by inciting urban mobs against Jews, Christians or others. The responsibility of Majlesi personally for a worsening of the situation from the reign of Shah Soleiman onwards has been disputed (for example, his treatise

Lightning Bolts Against the Jews

turns out on examination to be rather more moderate in setting out the provisions of Islamic law on the minorities than its title might suggest

27

) but he was an influential figure and was briefly to become dominant in the following reign. His voluminous writings also included strong blasts against Sunnis and Sufis. The movement was broader than just Majlesi (whom it may have suited to appear radical to one constituency and moderate to another) but it is important to remember that it represented only one strand of Shi‘ism at the time; other Shi‘a ulema were critical of Majlesi’s repressive policy.

28

As Shah Soleiman’s reign drew to a close, the Safavid regime looked strong, but had been seriously weakened; its monuments looked splendid, but the intellectual world of Persia, once distinguished for its tolerance and vision, was now led by narrower, smaller minds.

5

THE FALL OF THE SAFAVIDS, NADER SHAH, THE

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY INTERREGNUM, AND

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE QAJAR DYNASTY

Morghi didam neshaste bar bareh-e Tus

Dar pish nahade kalleh-e Kay Kavus

Ba kalleh hami goft ke afsus afsus

Ku bang-e jarasha o koja shod naleh-e kus

I saw a bird on the walls of Tus

That had before it the skull of Kay Kavus.

The bird was saying to the skull ‘Alas, alas’

Where now the warlike bells? And where the moan of the kettledrums?

∗

(attributed to Omar Khayyam)

According to a story that was widely repeated, when Shah Soleiman lay dying in July 1694 (1105

AH

), he left it undecided which of his sons should succeed him. Calling his courtiers and officials, he told them—‘If you desire ease, elevate Hosein Mirza. If the glory of your country be the object of your wishes, raise Abbas Mirza to the throne.’

1

Once Soleiman was dead, the eunuch officials who supervised the harem decided for Hosein, because they judged he would be easier for them to control. Hosein

was also the favourite of his great-aunt, Maryam Begum, the dominant personality in the harem; and he duly became Shah.

Such stories present historians with a problem. Their anecdotal quality, though vivid, does not fit the style of modern historical writing, and even their wide contemporary currency cannot overcome a reluctance to accept them at face value. The death-bed speech, the neat characterisation of the two princes, the cynical choice of the bureaucrats—it is all too pat. But to dismiss it out of hand would be as wrong as to accept it at face value. It is more sensible to accept the story as a reflection of the overall nature of motivations and events, even if the actual words reported were never said. The story reflects the impression of casual negligence, even irresponsible mischief, that we know of Shah Soleiman from other sources. As the consequences will show, it also gives an accurate picture of the character of Shah Sultan Hosein, and the motivation of his courtiers. It is quite credible that Shah Soleiman left the succession open, and that over-powerful officials chose the prince they thought they thought would be most malleable.

Initially, Shah Sultan Hosein appeared to be as pious and orthodox as Mohammed Baqer Majlesi, the pre-eminent cleric at court, could have wished. Under the latter’s influence the bottles from the royal wine cellar were brought out into the

meidan

in front of the royal palace and publicly smashed. Instead of having a Sufi buckle on his sword at his coronation, as had been traditional (reflecting the Sufi origins of the Safavid dynasty), the new Shah had Majlesi do it instead. Within the year orders went out for taverns, coffee-houses and brothels to be closed, and for prostitution, opium, ‘colourful herbs’, sodomy, public music, dancing and gambling to be banned along with more innocent amusements like kite-flying. Women were to stay at home, to behave modestly, and were forbidden to mix with men that were not relatives. Islamic dress was to be worn. The new laws went through despite the protests of treasury officials, who warned that there would be a huge drop in revenue, equivalent to 50 kg of gold

per day

, because the state had made so much money from the taxation of prostitution and other forms of entertainment. To make sure the new order was widely publicised, it was read out in the mosques, and in some it was carved

in stone over the door. A later order stipulated that Majlesi, as

Shaykh oleslam,

should be obeyed by all viziers, governors and other secular officials across the empire. Anyone who broke the rules (or had done so in the past) was to be punished.

2

It was a kind of Islamic revolution.