Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes (16 page)

Read Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes Online

Authors: Kamal Al-Solaylee

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Middle East, #General

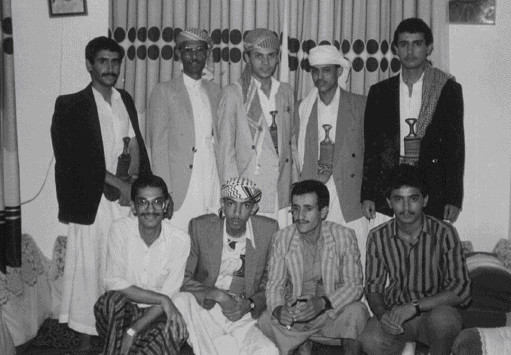

In 1988, I was invited to a social gathering with a group of men from Sana’a who were, like me, fulfilling their military service. I have no recollection of their names. As I look at the picture, I barely recognize myself—I’m sitting down, far left—let alone the others.

As a man, I knew at least that I had the gender advantage in Sana’a. I could go out wherever I wished, and if I chose to travel, I didn’t need a male companion’s approval. When my sisters would visit us in Cairo, my brother accompanied them to the Sana’a airport to sign off on documents to indicate his approval of their travel plans.

“You’re lucky to be a man,” my sister Raja’a—who, like me, loved American movies and grew up adoring Tom Jones—would tell me. She was married for one year to a Yemeni man who lived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and had a daughter in 1987 before her husband more or less abandoned her and married another woman. Her life was effectively ruined—a single, divorced mother at twenty-eight had few prospects in Sana’a’s ultraconservative society. It took her almost three years to get a divorce in absentia. She never saw her husband again.

My sister Hanna was also unhappy with her domestic situation, having been forced into marriage with a man she didn’t know well. Both sisters grew up watching romantic Egyptian and Hollywood movies and felt betrayed by what the move to Yemen had done to their dreams of independent and free lives. Watching those same movies or listening to the same music in their company at times became unbearable as they quietly wept, doing their best to hide their tears.

Slowly, both sisters started to turn to religion as a way of licking their wounds. They insisted that they found praying or reading the Quran to be comforting, that it didn’t mean they were becoming hardline or intolerant like many other people around them. It seemed to be a coping mechanism. Naturally, Helmi was supportive of their discovery of Islam and praised them for following their rightful path in life. Any attempt on my part to get them to return to our secular roots would have been seen as interference. My two other sisters, Hoda and Ferial, were unmarried and seemed to have resisted the tide of sudden religiosity for now. They talked of trying and failing to get out of Yemen. Hoda was engaged briefly to an Egyptian and was secretly hoping he’d relocate to Cairo so she could follow him. Ferial would go on any business trip or to any conference the USAID would send her. But despite all these escape attempts, they eventually accepted Sana’a as their home. “We’ll be buried here,” Hoda would say, part in jest, part in desperation.

I was determined not to fall into the same trap. I felt guilty for turning my back on them and plotting my exit strategy without them. But it was easier that way. My fate couldn’t be the same as theirs. My father sensed what was happening and tried to dissuade me from any plans to immigrate or study abroad. It’ll break your mother’s heart, he cautioned. I knew that, but it was either her heart or mine. I didn’t have the luxury of saving both.

But just as things were getting serious, along came some moments of comic relief. Because the number of women outnumbered men in Yemeni society, it wasn’t that uncommon for matchmakers to visit family homes with details of brides who might make suitable matches for the men in well-to-do households—sometimes even married males, as Muslim men have the right to marry up to four, although that remains a rare arrangement. Word must have got out that Wahbi and I were single and in our twenties, even though he was still in university and I had no job. I’d get a kick out of hearing out various descriptions of women—they were always beautiful and dutiful—who might one day make me a happy and contented man. Now that I’ve lived in the West for nearly a quarter of a century, I look back at that phase of life as if I’m watching a Bollywood movie in my head where my family and I played the leads.

Traditionally, the matchmakers visited on Friday evening, which clashed with my favourite radio show on Voice of America, featuring the countdown of the

Billboard

Top 20 singles chart. I realize it must sound strange to be listening to which song climbed to Number 1 in the United States with one ear and marriage plans involving complete strangers with the other. But I was used to living a double life by then. My brother and I sat through the descriptions of the women just to please the matchmakers. Even my sisters and my mother—bless them—didn’t approve of being married that way and merely humoured the matchmakers.

I often wondered if any of my sisters had by then guessed that I wasn’t interested in women at all. Perhaps they were just trying to protect me or play the game by going through the motions with the matchmakers. It would throw my brother and father off my gay scent for a little while at least.

EVEN THOUGH FERIAL

worked in the USAID, I didn’t stand a chance of continuing my studies in the United States. Most of the scholarships offered by the US government were in effect bribes for the children of rich and powerful business people and the ruling class in exchange for favourable contracts for American businesses or for gaining political ground in the region. Besides, most of the scholarships focused on science and technology, making my proposed English major an even longer shot. Britain, therefore, seemed a more manageable destination. The local British Council offered a range of scholarships that had no specific area of study attached to them. But those, too, were competitive and usually came with a long waiting list. I needed to find a shortcut. If I waited too long in Yemen, perhaps I’d follow in my siblings’ defeatist footsteps.

Luckily, a teaching-assistant position in an English language program at Sana’a University opened up. I knew at the interview that I’d got the job since the interview committee, made up of English and American professors, commented on my English proficiency. Step one accomplished. I could network with the British and American staff and seek advice or, more importantly, reference letters. I didn’t have much to do during the day, as most classes were in the evening, so I started to make a list of all the great works of English literature that I hadn’t read and went through them one by one at the British Council library. It all sounds very colonial, even to my ears now: reading Jane Austen or Charles Dickens in Yemen during the monsoon season, in the library of the British Council. This took place at a time before terrorism and attacks on Western targets were to define Yemen in the eyes of the world. The British Council was in an old house on a side street in Sana’a’s downtown. The only security was an old befuddled Yemeni guard whom I got to know well that year. All you needed was to show your membership card. He often left his post to attend prayers, so you could walk in without a card if you timed your visit right. His son, then about nine or ten, filled in for him when he got sick.

It was, in retrospect, a charmed life. The only reminders that I was in Yemen while inside the British Council were the calls to prayers. The Council also gave away old copies of the

Times

and

Daily Telegraph

, my introduction to serious journalism in English and my window into social, especially gay, life in the UK. I read whatever I could lay my hands on: magazines, newspapers, books. As long as it was written in English, I’d read it. English was, and would continue to be, my escape route from Yemen, my path to an openly gay life. I was certain of it. After all, English had already served me well in that regard in Egypt.

I called that one right. It wasn’t long before I impressed the head of the school, an older English gentleman who’d taught in several Third World countries. He told me about a private scholarship that the Council offered a Yemeni applicant who was deemed worthy of support and a chance at a British education. He’d talk to the right people about it and get back to me. In a way, I thought it was too good to be true, too easy to happen that quickly. A few weeks later, I had a firm offer of financial support if I landed a place at a British institution where I could quickly get a B.A. equivalency and study for a master’s in English. It was at most a two-year grant, after which I had to return to Sana’a. Since I had no other offers and stood no realistic chance of getting anything near as generous, I accepted, without telling anyone in my family. Two years in Britain would give me enough time to plan ahead. From there I could go to the States. Imagine: living in New York. One thing I had no intention of doing was going back to Yemen. After applying to several universities, I accepted the first offer I got, from Keele University in Staffordshire, not even knowing where it was on the map. Without a place, I had no scholarship, or I’d have to wait another full year. I had been in Yemen for about sixteen months and I just couldn’t stand being there (and being celibate) for another year.

Now came the hard part. Telling my mother that I’d be away for at least two years. I knew how upset she’d be. She’d already hinted that the only thing that kept her going in Sana’a was having her children close by. Her husband provided no comfort. Two decades of trying and failing to restart his business had turned Mohamed into a bitter and argumentative man. In the past he could claim that Lebanese and Egyptian business ethics didn’t suit his. Now, in his home country, what was his excuse? I don’t think Mohamed or Safia had said a word to each other in over a year. After more than forty years of marriage, it was as if they had separated. They’d survived his womanizing, her inability to give him a son until the fifth pregnancy, expulsion from Aden and exodus from Beirut and Cairo, but not Sana’a. Mohamed had his own quarters in the house, and we rarely saw him, anyway. To leave my mother now, when she probably needed me the most, would be extremely selfish. I tested out the idea by telling her that I might be going for some training in the UK for a few weeks. She seemed pleased for me and added that I could visit Faiza and my aunt in Liverpool. Then I dropped the bomb. “Well, I may also go for a full year or two.” To my surprise, she didn’t seem to mind. She knew how unhappy I was in Sana’a. She said one word that captured it all:

ihrab

, escape. I was stunned. I expected tears and strong opposition. I expected her to beg me to forget about the scholarship and stay close to the family. But after a short silence she repeated that word: escape.

Run for your life, she might have added. Later she told me that the news devastated her, but she’d learned to give priority to her children’s happiness. As I needed a bit more cash to get me through the transition, she sold her favourite gold bracelet, a family heirloom, to help me buy some sterling in the old market in Sana’a. We had to keep it a secret, as even my sisters would have thought it a major sacrifice and talked her out of it. I never got around to buying her a replacement bracelet. I still regret it.

Leaving my sisters was more difficult. Plotting my escape had been easy; it had all seemed so remote and far-fetched. It was real now. As a moderate male voice in the family, I knew that my sisters would lose an important ally. Yemen was the end of the line for them. I tried to rationalize it. Well, if they, too, studied hard they might have received scholarships and left the country. Or if they married rich, they could travel out of Yemen more often. It didn’t matter much in the end. I managed to break away because I wanted it so badly and because I was a man. While they were all happy for me, they knew that baby brother Kamal would be leaving the nest for good, abandoning them to look after two parents who lived in a state of indifference to each other.

My sisters’ capacity for sacrifice was (and still is) something I accepted as fact but could never understand. I don’t do sacrifice, unless it’s a temporary measure to achieve a higher goal down the road. Certainly, part of their ability to suffer and sacrifice came from gender expectations in that society, but I think a bigger part simply had to do with life in Yemen. In a world that cut choices short for women, sacrifice gave you something to do—it was an achievement of a sort, a choice, so to speak.

I spent my last few weeks in Sana’a both counting the days and wishing time would go slowly. I couldn’t wait to get out, but wanted to stay longer with my mother and sisters. I knew I had no intention of ever going back. Somehow I was less attached to my brothers and father. Being gay made me side with the women in the family and stop acting like a man around the house. That said, there was little evidence of machismo around the family home on my last night in Sana’a. Tears, hugs, advice. Helmi gave me a copy of the Quran to keep with me at all times for protection. I left it at home. My father repeated one of his stories from his time in London after the Second World War. My mother sobbed quietly in the kitchen as my sisters took turns calming her down.

I had to be strong. Sentimentality would hold me back. I was finally going to be doing what I’d dreamed of for years: living in England and possibly openly as a gay man.

I

kept looking at the UK visa stamped on my passport. My letter from the British Council was tucked into the inside pocket of the oversized black jacket I’d bought from a street vendor in Sana’a a few days earlier. I wanted to make sure that neither my passport nor that letter could slip out, so I looked for a jacket with a button on the inside pocket until I found one. It didn’t matter that it was two sizes too big for what was then my very thin body. I couldn’t risk losing the documents and delaying my journey to England or being prevented from entering the country.